Using PET perfusion to gauge cardiac blood flow capacity (CFC), researchers have found that severely reduced coronary flow reserve (CFR) is a key contributor to a greater risk of a major adverse cardiac event and death, according to a study published online November 18 in Cardiovascular Imaging.

When CFR is between 1 to 1.5 and stress perfusion is ≤ 1 cc/min/g, cardiac blood flow capacity is dramatically reduced. As a result, patients with this condition have a major adverse event rate of 80% and a mortality risk of 14%. Interestingly, even small areas where CFC is reduced can prompt an adverse event.

"Although increasing size of CFC [severity] predicts increasing risk of coronary-related events, even small regions of CFC [severity] predict high risk related to large border zones at risk defined by relative stress of ml/ min/g surrounding the small severe center," wrote lead author Dr. K. Lance Gould and colleagues from the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston.

It is well known that poor coronary flow reserve and stress perfusion characteristics are likely to cause a major adverse cardiac event or death. While revascularization can reduce the chances for a poor outcome, how other coronary-related factors might influence a patient's future is still unclear, according to the authors.

"First, what fundamental coronary physiological mechanisms for which quantitative perfusion metrics of what severity, if any, correlate with the highest major adverse cardiac events and mortality before and after revascularization?" the researchers posed. "Or do various perfusion measurements have merely parallel, overlapping, comparable predictive value?"

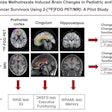

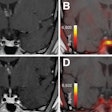

To delve into those questions, the researchers analyzed a total of 5,274 routine diagnostic cardiac PET scans (Discovery ST, GE Healthcare) with rubidium-82 (CardioGen-82, Bracco Diagnostics) from 4,995 patients with or at risk of coronary artery disease. The researchers defined CFCsevere as CFR equal to or less than 1.27 and stress perfusion equal to or less than 0.83 and plotted the PET results on color maps to determine the locations and degree of CFC severity. A prospective follow-up, which included whether a patient underwent revascularization and their clinical outcome, was conducted for up to 10 years (mean 4.2 ± 2.5 years).

At the 90-day follow-up mark, the researchers tallied 230 deaths (4%), with 134 deaths (14%) among 944 patients deemed CFCsevere. By comparison, 96 deaths (2%) occurred among the 4,091 patients who were not CFCsevere.

Over the course of 10 years, patients in the CFCsevere category also registered the greatest outcomes of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularization, "up to 80% over 10 years ... thereby indicating that the risks of CFR and stress perfusion are partly additive," the authors wrote. Even small regions of CFCsevere (≤ 0.5%) were predictive of a higher risk of mortality or adverse event.

As for the efficacy of revascularization, the risk of death among CFCsevere patients was lowered significantly (54%, p = 0.005) after revascularization, compared with no revascularization.

"The risks of adverse events from reduced CFR and stress perfusion in ml/min/g are additive, as quantified by their regional per pixel combination in CFC," Gould and colleagues concluded. "Regional CFCsevere incurs sufficiently high risk that revascularization significantly reduces mortality personalized for artery-specific stenosis not quantified by global or regional CFR alone."