Systemic Lupus Erythematosus:

View cases of SLE

Clinical:

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune collagen vascular disorder characterized by deposition of autoantibodies and immune complexes damaging tissues and cells [8]. SLE most commonly affects young females (about 10:1)- peak onset in the 2nd-4th decades [11]. There is also a higher incidence in blacks and a strong familial association. In children, males are affected 2-3 times more often than females [11]. Manifestations include a characteristic butterfly facial erythema, fever, malaise, and polyarthralgia without erosions. Lab abnormalities include autoantibodies directed against double stranded DNA, nuclear ribonucleoprotein, Smith (Sm) antigen, Ro/SS-A, and La?SS-B/Ha [9]. Pulmonary and pleural involvement has been reported with a wide range of incidence in patients with SLE. Findings include pleural effusion, alveolitis, interstitial fibrosis, BOOP, pulmonary vasculitis, pulmonary hemorrhage, and obliterative bronchiolitis. Other complications include a primary dilated cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease (non-bacterial verrucous- Libman-Sachs endocarditis), and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. SLE patients are also at a 9 fold increased risk for coronary artery disease.

Pulmonary and other manifestations of SLE include:

Infection: The risk of pulmonary infection is 3 times higher in patients with SLE compared to the general population [11]. Both intrinsic immunologic abnormalities and corticosteroid therapy contribute to this increased risk [11]. SLE patients have a slightly higher prevalence of TB and Nocardia infection [11].

Pleural disease: Pleural effusion has traditionally been regarded as the most common intrathoracic manifestation of SLE- probably because these patients come to clinical attention with complaints of pleurisy, cough, and fever. Clinically apparent pleural effusions have been reported in up to 50% of patients with SLE [9]. Pleuritis or pleural fibrosis can be found in 50-93% of patients at autopsy [3,9]. The effusions are bilateral in about 50% of cases [3,11]. On laboratory analysis the effusion may be clear/transudative, seroanguinous, or exudative (most common [9]). The glucose level is often elevated (greater than 56 mg/dl) and the fluid is often ANA (+), anti-DNA (+), and contains LE cells (specific for SLE pleural effusion) [9]. Treatment with steroids usually alleviates pain and fever, but the effusion resolves more slowly [3].

Interstitial lung disease: The presence of interstitial lung disease may be higher than the previously reported 1 to 13% of SLE patients; most likely due to the fact that many patients (82%) with HRCT evidence of interstitial lung disease are asymptomatic. Moderate or severe fibrosis is rare in patients with SLE [9].

Shrinking lung syndrome: Shrinking lung syndrome results from respiratory and diaphragmatic muscle dysfunction and can be found in up to 25% of patients. Lack of appropriate diaphragmatic excursion results in generalized atelectasis and reduced lung compliance, however, in this condition the DLCO remains normal. With assisted ventilation the lungs will re-expand. The CXR findings include low lung volumes and basilar atelectasis. [3,9]

Acute lupus pneumonitis: Acute lupus pneumonitis occurs in 1 to 4% of patients [10] (others report up to 12% of patients [11]). Patients with acute lupus pneumonitis present with abrupt onset on dyspnea, cough, pleuritic chest pain, fever (1-4% of cases [9]), and in some cases hemoptysis. The diagnosis of acute lupus pneumonitis is one of exclusion- other etiologies including infection must first be excluded. Post-partum patients are at an increased risk for developing acute lupus pneumonitis. Radiographic findings include bilateral or unilateral patchy alveolar opacities with a lower lobe predilection. Most patients have associated pleural effusions. Treatment is aggressive with corticosteroids, but an optimal treatment has not been clarified and mortality is still high. [3,9]

Alveolar hemorrhage: Among collagen vascular disorders, SLE is the most common cause of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage [12]. However, alveolar hemorrhage in SLE is still rare and varies from a mild, subclinical chronic form, to an acute life-threatening hemorrhage (the reported mortality rate for DAH in SLE is approximately 60% [13]). Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage can be seen in up to 3.7% of hospitalized SLE patients [12]. The clinical manifestations of severe pulmonary hemorrhage are similar to those of acute lupus pneumonitis with dyspnea, cough, fever, hemoptysis, and hypoxemia [12]. Both conditions may represent a spectrum of lung disease that results from injury to the alveolar-capillary unit (a necrotizing capillaritis [12]). Alveolar hemorrhage is usually seen in patients with high circulating titers of anti-DNA antibody and active extra-pulmonary disease (glomerulonephritis is often present in SLE associated alveolar hemorrhage) [9]. In up to 20% of cases, alveolar hemorrhage may be the initial manifestation of SLE. The presence of gross blood in the airways, serosanguinous BAL fluid, hemosiderin laden macrophages, the absence of purulent sputum, and the lack of infectious organisms on culture establish the diagnosis of alveolar hemorrhage [9]. The treatment of choice is high dose corticosteroids with or without cyclophosphamide [9]. Plamapheresis has also been used for the treatment of this condition [9]. Chest radiographs show ill-defined, patchy alveolar opacities with a bilateral lower lobe predominance or diffuse alveolar infiltrates in more severe cases. In patients with severe pulmonary hemorrhage, mortality is 50-90%. [3,9,11,12]

Vasculitis: Lupus vasculitis is a serious complication of the disease. It may affect the lungs, heart, spleen, skin, kidneys, or other organs.

Acute Reversible Hypoxemia: Acute reversible hypoxemia is thought to be secondary to complement split products which activate neutrophils, clog capillaries, and cause diffuse hypoxemia in the lung. Chest radiographs are normal. It is reversed with high dose steroid therapy. [3,9]

Pulmonary artery hypertension: PAH may develop as a result of small pulmonary artery vasculitis, thrombosis in situ or pulmonary thromboembolism. PAH is more common in SLE patients with antiphospholipid antibody (APA) syndrome- likely due to recurrent emboli (PAH develops in 25% of SLE patients with APA syndrome) [11]. Patients with SLE may also develop primary pulmonary artery hypertension [3]. Raynauds phenomenon is present in 75% of cases [9]. The overall prognosis is poor with a two year mortality exceeding 50% [9]. Treatment is similar to that used for primary pulmonary hypertension [9].

Anti-phospholipid Antibody syndrome: Antiphospholipid antibody (APA) syndrome is characterized as either primary, or secondary. Secondary APA occurs in patients with a concurrent diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosis. The prevalence of APA in SLE patients may be as high as 27-42% [11]. Two major types of APA are recognized, anticardiolipin antibody and lupus anticoagulant. Both of these antibodies are thought to cross-react with negatively charged phospholipids found within cell membranes. Affected patients have a hypercoaguable state and are at increased risk for venous and arterial thrombosis, stroke, and pulmonary arterial hypertension. The complete syndrome consists of multiple thromboses, early stroke, livedo reticularis (purplish mottling of the skin due to vascular insufficiency), recurrent fetal loss, thrombocytopenia, and cardiac valvular abnormalities (Libman-Sacks-type endocarditis). Thromboses tend to recur in the same portion of the vascular system as the initial event. Patients require treatment with long term, high dose anticoagulation. [5,6,7]

Drug induced lupus: Drug induced lupus differs from primary SLE by it's lack of CNS or renal disease [3]. It may result from therapy with procainamide or hydralazine (most commonly); other drugs which may also produce lupus include dilantin, penicillamine, phenytoin, and chlorpromazine. Patients are usually ANA (+), but anti-DNA antibody negative. Affected patients commonly develop pleural and pericardial effusions. The effusions are usually exudates and are sometimes serosanguineous [3]. Treatment is discontinuance of the affecting agent, and steroids if necessary.

X-ray:

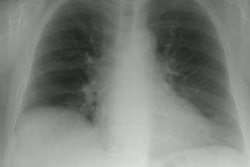

CXR: Pleural effusion is often the first manifestation of SLE. Between 15-50% of patients will demonstrate the presence of a pleural effusion and the effusion is bilateral in up to 50% of cases. Pneumothorax will often occur in association with the pleural effusion.

Computed tomography: HRCT is superior to plain film CXR in detecting pulmonary disease in SLE patients (38-70% versus 6-24% of cases). Findings include thickening of the inter- and intralobular septa (33 to 50%), parenchymal bands, architectural distortion, bronchiectasis or bronchial wall thickening (20-35%), pleural irregularities, areas of ground glass attenuation (4), air space nodules, and even mediastinal or axillary adenopathy (16%).

REFERENCES:

(1) AJR 1996 Feb;166(2):301-307

(2) Radiology 1995 Sep;196(3):835-840

(3) J Thorac Imag 1992; 7(2): 1-18

(4) AJR 1997; Ground-glass opacity at CT: the ABCs. 169(2), 355-367 (No abstract available)

(6) Radiology 1997; 202: 319-326

(7) AJR 1998; Provenzale JM, et al. Systemic thrombosis in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies: Lesion distribution and imaging findings. 170: 285-290

(8) Society of Thoracic Radiology Annual Meeting 2000 Course Syllabus; Erasmus JJ. Pulmonary drug toxicity: Pathogenesis and radiologic manifestations. 65-68

(9) Thorax 2000; Keane MP, Lynch JP. Pleuropulmonary manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. 55: 159-166

(10) Radiographics 2002; Kim EA, et al. Interstitial lung diseases associated with collagen vascular diseases: radiologic and histopathologic findings. 22: S151-165

(11) Radiographics 2004; Lalani TA, et al. Imaging findings in systemic lupus erythematosus. 24: 1069-1086

(12) AJR 2005; Marten K, et al. Pattern-based differential diagnosis in pulmonary vasculitis using volumetric CT. 184: 720-733

(13) Radiographics 2010; Castaner E, et al. When to suspect pulmonary vasculitis: radiologic and clinical clues. 30: 33-53