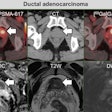

Back pain is a huge global problem that ranks among the top 10 causes of disability. Medicine has leapt to the rescue with billions of dollars worth of imaging and surgery to treat the suffering. However, neither option does patients much good most of the time, and it's time to standardize care for the patient's sake, said Total Radiology keynote speaker Dr. Michael Modic at last month's 2014 Arab Health meeting in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

The huge cost of back pain care is unsustainable over the long haul, especially in an era when doctors are "being paid less and ... being subjected to more transparency than ever before," said Modic, who is chairman of the Neurological Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

What's the solution? Not the one we're currently chasing, he said. Imaging has little to no value for back pain, and surgery also has little value for most back conditions. The solution in the vast majority of cases is to skip imaging and surgery in favor of conservative management.

"With imaging we find we're average in reproducibility, revealing a condition that has a very favorable natural history on its own, and we know that the value of imaging for conservative management is really low," he said.

As for surgery, the definitive study on the topic found essentially no difference in outcomes between surgery and conservative management for a herniated disk, though surgery did help for symptomatic stenosis. Spinal fusion showed equal outcomes regardless of the treatment approach or cost.

When half of patients presenting with back pain are being imaged, and more than 1 million back surgeries are performed every year despite shaky evidence, something needs to change drastically, Modic said.

"We need to fundamentally take care of patients differently," he said. "We need to standardize what we do [using] evidence-based data to reduce unnecessary variation and continually measure what we do. We can't be 100 million practitioners across the planet practicing the way we feel rather than in a standardized fashion."

Big problems

A large 2012 study revealed the extraordinary scope of the back problem. Disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) rankings show that between 1990 and 2010 the prevalence of back pain increased by 43% and neck pain increased by 41% (Lancet, December 15, 2012, Vol. 380:9859, pp. 2197-2223).

With people living longer, the sequelae of their back problems are growing more severe. Now taking sixth place among causes of disability, lower back pain showed one of the greatest increases over 20 years. "Today, lower back pain lives between AIDS and malaria in terms of disability, and I think that's fairly significant," Modic said.

Back pain generates major income for healthcare providers, he noted. Lower back pain is now the ninth most expensive medical condition to treat. Between 1997 and 2005, the cost of the average episode of care for lower back pain rose from $4,800 to $6,100 -- a 65% increase over eight years. Unfortunately, though, it's not making patients any better, he said.

Who does what and why

So is there too much surgery or too much imaging? That's a harder question to answer, according to Modic. "What value do we bring with either one? In the U.S., surgery rates continue to increase, but not in a standardized fashion," he said.

A 1996 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association (Verrilli and Welch, Vol. 275:15, pp. 1189-1191), for example, showed that population rates for diskectomy varied by 10-fold across hospital referral regions, and rates for spinal fusion differ by 15-fold. In some parts of the U.S., a patient with back pain is 15 times likelier to have a diskectomy than in other parts of the country, according to a survey in the Wall Street Journal. The reason is the complete lack of standardized care, Modic said.

In some locations such as Louisville, KY, surgery rates can be so high "that I would be afraid to stop at a red light" for fear of being referred, he added, noting that Louisville also had high rates of surgery for patients with back pain only. "If you go to other parts of country, the rate of surgery is incredibly less," he said.

Imaging vs. surgery

In their study, Verrilli and Welch found a moderate to strong correlation between imaging and surgery, so the two are clearly associated, Modic said. Which came first is a chicken-or-the-egg question.

"Are we doing too much imaging because we're doing too much surgery, or are we doing too much surgery because we're doing too much imaging?" Modic said. One thing's for sure, "if our imaging doesn't affect [surgeons'] decision-making, we're probably doing too much of it."

The literature shows that clinicians and imaging produce excellent agreement (0.93) for level and location of injury, but only fair agreement (0.24) for comparing morphology. "What clinicians see and what radiologists see are two different things; there's a huge gap between what we're doing and what surgeons and clinicians see," he said.

Dr. Michael Modic from the Cleveland Clinic speaking at Total Radiology.

Dr. Michael Modic from the Cleveland Clinic speaking at Total Radiology.

And the burden of disease is tremendous. When Boden and colleagues used MRI to examine 100 subjects (Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, March 1990, Vol. 72:3, pp. 403-408), two-thirds of whom were asymptomatic, they found that 20% of those younger than 60 years had a herniation (HNP, herniated nucleus pulposus), and the figure rose to 36% for those 60 and older, Modic said.

"What is the importance of knowing whether a disk is degenerated or not, given that everybody in this room probably has a degenerated disk?" he asked. "What value is there in knowing a person has a stenotic canal? Do we really understand what impact it has on deciding what the patient will do? We're pretty good at seeing herniation, but only fair at quantifying stenosis. Agreement is only poor to fair as to what's causing the morphologic abnormality."

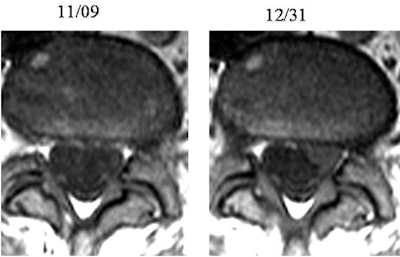

Morphologic abnormalities don't necessarily mean the patient will be in pain. Jensen and colleagues reported in the New England Journal of Medicine (July 14, 1994, Vol. 331:2, pp. 69-73) that 28% of people without back pain had a herniated disk, Modic said.

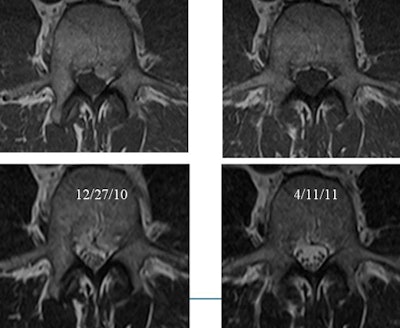

In their own study, Cleveland Clinic researchers followed for two years 246 patients who had a variety of functional pain issues. Sixty-four percent of those with back and leg pain had a herniation on imaging, and 57% of those with back pain had a herniation.

However, over six weeks there was complete resolution in 23% of those with herniation. Also, 13% of those with herniation developed a second herniation between the first and second studies (Radiology, November 2005, Vol. 237:2, pp. 597-604).

"There is no correlation between the number of herniations and how big they were and the patient's symptoms, and whether they were herniated didn't seem to correlate with how the patient did," Modic said.

Spine MRI of patients presenting with back and left-leg pain on December 27, 2010. Patients were treated conservatively and both pain and disk herniation resolved before repeat imaging on April 11, 2011. All images courtesy of Dr. Michael Modic.

Spine MRI of patients presenting with back and left-leg pain on December 27, 2010. Patients were treated conservatively and both pain and disk herniation resolved before repeat imaging on April 11, 2011. All images courtesy of Dr. Michael Modic.

The study determined several factors that did not predict outcomes, including the kind of pain experienced by the patient and whether or not it went away. Nerve compression, stenosis, randomization, gender, and the type, level, and number of herniations -- none of them mattered, he said.

Only two factors affected outcomes: race (odds ratio [OR] 3.2) and the presence of herniation at baseline (OR 2.92), according to Modic. Caucasians were three times more likely to do well than noncaucasians (the figures were adjusted for socioeconomic group), he said.

The Cleveland Clinic study also found that patients who had a herniation were three times more likely to do well if they were managed conservatively.

"If you have a herniation, you have a morphologic disorder that has a favorable natural history -- most herniations go away -- whereas if you don't have a herniation, you may have a more complicated multifactorial cause of pain, and its natural history may not be as favorable," Modic said.

Finally, the study showed that the 50% of patients who knew about their herniation were unhappier about their health, compared with those who weren't told of the imaging results.

"So, in this case, the presence of inflammation had a deleterious effect on patients' perceptions of their health," he said. Patients want the imaging exam, of course, but there is strong evidence that the information the study provides is not helpful to them.

Patient had left radicular symptoms at presentation but no herniation at MRI. At follow-up imaging, pain decreased significantly but disk herniation became visible.

Patient had left radicular symptoms at presentation but no herniation at MRI. At follow-up imaging, pain decreased significantly but disk herniation became visible."There is a huge number of patients we're imaging every day, and the literature says not to image them," Modic said. "So if they don't have red flags, if they don't have yellow flags, you need to look at the care model and fundamentally take care of patients differently."

But skipping the imaging is easier said than done. Cleveland Clinic research has also shown that 40% of back pain patients were imaged on their first visit, according to Modic.

"The good news is that most of them were plain films. Now, I don't know about you, but the value of a lumbar spine radiograph for me is to establish the presence of a spine," he quipped. "That's an important piece of information that a radiograph can provide; if you're concerned this might be an alien species, a radiograph can help."

In all seriousness, there is a wealth of evidence-based guidelines for patients in the acute and subacute phases, he said, and there is still plenty of room for innovation along the care pathways that have already been laid out and validated.

"But by and large we don't follow the evidence-based guidelines that are out there," Modic said. "We need to standardize what we do ... reduce unnecessary variation and continually measure what we do."

Surgical success

Like imaging, surgery isn't routinely helpful either, Modic said. According to the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT), among patients with herniation, there was no statistically significant difference in outcomes at two years postsurgery whether patients were treated with surgery or conservatively. At four years, there was a slight tendency toward better outcomes with surgery.

Stenosis was a slightly different story: Symptomatic stenosis patients undergoing surgery improved more than patients who were treated conservatively (Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, March 2012, Vol. 20:3, pp. 160-166).

Spinal fusion is also problematic because of wide cost variations.

"Fusion has many meanings, and those meanings can cost between $8,000 and $80,000," Modic said. "There was no difference between types of fusion and outcomes, but there was significant difference in cost."

For example, a posterolateral fusion averaged $15,000 to $20,000, while a transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion came in at $90,000; there were no differences in outcomes. And while medical device companies have wielded influence in pushing their products, funding studies and even manipulating the results, outcomes have not justified the expense as of yet, he said.

"The right patient operated on will have a reduction in symptoms sooner than the patient with conservative management, [but] basically you're going to get better whether you have surgery or not," Modic said.

New world ahead

There's one more reason why current care patterns are unsustainable, according to Modic. Reimbursement today is based on a fee-for-service model in most places and encourages overtreatment, but tomorrow's payment model will rely on value -- characterized by bundled payments based on episodes of care.

"We need to be incentivized to follow algorithms based on standardized care," he said. "We need to somehow remove counterincentives financially in terms of what we do on a volume basis" and focus on providing value to the patient. "This is where things are really changing, not just in the United States but in the world."

Currently, there is too much imaging and too much surgery, and the solution is standardized care, he said.

In that sense, "financial pressures are a good thing, driving us to do the right thing, not just economically but from the viewpoint of the patient," Modic said. "I think we have a social responsibility to do what's best for the patient."