New research has shown that dark-field x-ray can be clinically effective in humans -- in this case, diagnosing emphysema in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), according to a study in the November issue of Lancet Digital Health.

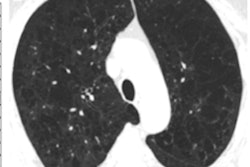

German researchers designed and built a dark-field chest x-ray system and tested its performance for early detection and quantification of emphysema in COPD patients. They found that dark-field x-ray detected structural impairments associated with emphysema in tiny alveolar surface areas of the lungs.

"The first patient results confirm that x-ray dark-field chest imaging can detect structural impairments associated with COPD, which remains challenging using only conventional chest x-rays," wrote first author Konstantin Willer and a team led by Franz Pfeiffer, PhD, chair of biomedical physics at the Technical University of Munich.

The finding suggests the new method could offer a low-radiation-dose alternative to standard CT in patients with COPD and potentially other lung disorders.

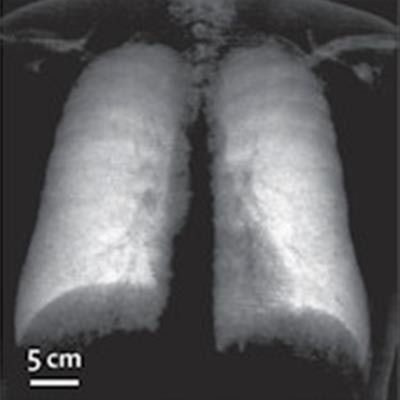

X-ray dark-field chest imaging exploits the wave-like behavior of x-rays to detect, quantify, and visualize small-angle x-ray scattering at interfaces between air and tissue in alveoli in the lungs. In attenuation-based radiography, signals are generated by dense structures, while in dark-field imaging, signals are produced by the small-angle scattering of x-rays in lung tissue.

Because dark-field x-ray imaging excludes unscattered photons, the space around the lungs appears dark (since there is no material there to scatter photons); hence, its name. The method essentially provides a visual look at alveoli tissue structures, which suggests it can help identify changes involved in lung disease.

In previous preclinical studies, Pfeiffer, who developed the technique in 2008, and colleagues have shown x-ray dark-field radiography can deliver complementary imaging information on the microstructure of the lung. In the new study, the team sought to assess the method clinically for the first time in humans.

The researchers recruited 77 patients at their hospital with healthy lungs or signs of emphysema who had undergone chest CT between October 2018 and December 2019. X-ray dark-field images and CT images were acquired and visually assessed by five readers. Pulmonary function tests (spirometry and body plethysmography) were performed for every patient, and for a subgroup of 42 patients, the researchers measured lung diffusion capacity.

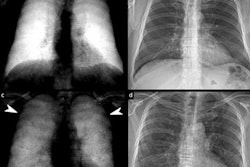

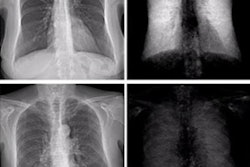

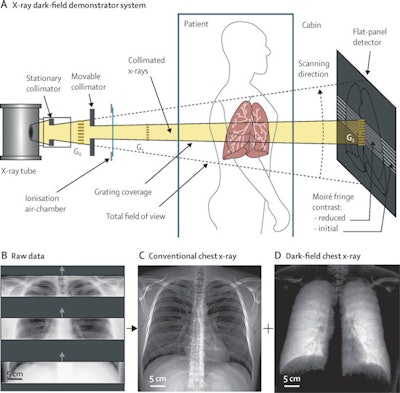

Schematic of the x-ray dark-field demonstrator system (A) and examples of raw detector imaging data (B), retrieved conventional chest x-rays (C), and dark-field chest x-rays (D) from the first in-human application.

Schematic of the x-ray dark-field demonstrator system (A) and examples of raw detector imaging data (B), retrieved conventional chest x-rays (C), and dark-field chest x-rays (D) from the first in-human application.Compared with CT-based parameters (quantitative emphysema and visual emphysema), the dark-field signal yielded a stronger correlation with diffusion capacity, a measure of how well oxygen and carbon dioxide are transferred (diffused) between the lungs and the blood, the authors reported.

In addition, they noted that the dark-field signal decreased with decreasing lung function, and that dark-field imaging correlated with measures of lung air capacity and volume.

"This study marks the transition from investigating artificially induced disease models to evaluating the modality's actual diagnostic performance in patients," the authors wrote.

The researchers noted that the dark-field x-ray system works on modified standard x-ray machines and that the model they used in this study included final alterations based on previous preclinical studies. Clinical demands regarding safety, usability, acquisition time, radiation dose, field of view, and image quality have been met in previous studies, they added.

In a commentary on the study, radiology research fellow Sundaresh Ram, PhD, and pulmonary and critical care specialist Dr. MeiLan Han of the University of Michigan wrote that early detection of COPD is a worthy goal, as COPD is currently the third leading cause of death worldwide.

However, dark-field metrics will need to be validated in large, multiethnic cohorts before the technique can be considered as a screening tool for established disease. For instance, correlation of dark-field metrics with longitudinal data indicating progression to airflow obstruction will be required to show that the abnormalities identified are clinically significant.

Overall, the study presents an interesting technology for pulmonary imaging and provides a methodology to spur much-needed action for assessment of pulmonary microstructural changes in routine clinical practice, Ram and Han wrote.

"Some of the greatest potential use for this technology is yet to be explored," they wrote.