Radiologists can play a key role in identifying cases of elder abuse in emergency departments, particularly if they develop an eye for "mechanism mismatch," says a group at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City.

The researchers reviewed medical literature for imaging of cases of elder abuse and found that while knowledge about the most common injury patterns is still emerging, evidence suggests victims are most likely to sustain radiographically visible injuries to the face, upper extremities, and head.

In all cases, assessing whether the extent of injury is concordant with the reported mechanism is critical, they wrote.

"The radiographic finding of a 'mechanism mismatch,' that is, an injury or fracture pattern inconsistent with the mechanism being described by the patient or their caregivers, is a critical finding that should trigger concern," wrote corresponding author Dr. Mihan Lee, PhD, a third-year radiology resident, and colleagues (Radiologic Clinics of North America, October 6, 2022).

Elder abuse in community-dwelling adults is estimated to be 10% and 20% among residents of nursing homes, with prevalence only expected to increase in future years due to the anticipated growth of the geriatric population. Despite the urgency of this problem, elder abuse continues to be deeply underdiagnosed, with as few as one in 24 cases identified and reported to the authorities, the authors wrote.

Moreover, many abused older adults are isolated, and an emergency department visit for acute injury or illness may be the only time they leave their homes, they added.

In this research, Lee and emergency department colleagues used preliminary studies of geriatric assault as a proxy for physical elder abuse. Elder victims of assault sustain distinct patterns of injury, with positive imaging findings primarily localized to the face, head, and upper extremities, in that order, the authors found.

These findings appear to be in keeping with information about mechanisms of injury available from clinical notes, which suggest that elders are most commonly punched/hit (apparently about the face), followed closely by being pushed to the ground (where they would plausibly catch or brace themselves on the upper extremities), the researchers wrote.

The authors noted that facial fractures appear to be significantly more common than intracranial injury and that the most commonly fractured facial bones are the nasal bones, followed by maxillary and orbital fractures.

In addition, wrist and forearm fractures are particularly common, such as the classic Colles fracture. "Nightstick" fractures may also occur when a victim pronates and flexes at the elbow to block an overhead blow, exposing the ulna to direct impact, they wrote.

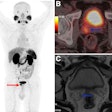

An anteroposterior radiograph of the left forearm of a patient demonstrates an acute minimally displaced fracture of the ulnar diaphysis (white arrow), compatible with a “nightstick fracture.” Image courtesy of Radiologic Clinics of North America.

An anteroposterior radiograph of the left forearm of a patient demonstrates an acute minimally displaced fracture of the ulnar diaphysis (white arrow), compatible with a “nightstick fracture.” Image courtesy of Radiologic Clinics of North America."Better characterizing these patterns can help diagnostic radiologists improve their ability to identify cases of potential intentional injury among cases of purportedly accidental trauma and ultimately serve as a first step in improving their sensitivity for physical elder abuse," the authors wrote.

Ultimately, significant knowledge gaps remain on how to use imaging to assess potential abuse, and most radiologists in the U.S. do not receive training in elder abuse identification, the authors wrote.

At present, clinical providers informing radiologists about how the patient purportedly sustained injuries is critical for radiologists to comment on whether their injuries are concordant, the authors wrote.

One future direction could be to design and pilot hands-on training modules for radiologists to gain exposure to elder abuse and its detection and management strategies, the authors suggested.

"Researchers and clinical leaders should explore the workflow and context within which radiologists work and develop changes to help them partner more effectively with frontline clinicians in an elder abuse assessment," Lee and colleagues concluded.