See your doctor regularly. A nice sentiment, but is it practical in this age of cheap information and costly medical care? Is it logical at a time when Medicare won't pay for a yearly physical, but the local drugstore offers screening tests by the dozen?

As economic and cultural pressures bear down hard on healthcare's traditions, it's time to give the maligned whole-body CT exam a second look, according to Dr. Michael Brant-Zawadzki. He is a clinical professor of radiology at Stanford University in Palo Alto, CA, and medical director of radiology at Hoag Memorial Hospital in Newport Beach, CA, in addition to his work at a Southern California imaging center.

A consumer-driven healthcare model is taking shape in the U.S., driven by powerful economic, cultural and technological forces, Brant-Zawadzki said at the 2002 International Symposium on Multidetector-Row CT in San Francisco. In his view, whole-body CT screening makes more sense than the government and organized radiology might lead one to believe.

"Why are individuals self-referring for this study despite the controversies...? We're getting older, and graying boomers are more interested in life-span prolongation," he said. "They have a little more money in their pockets, although that may have diminished somewhat. They have greater access to information about medicine, their health, and what to do about it, and they are being forced into medical self-empowerment."

Forced, that is, by a paternalistic payor-physician culture that controls the practice of medicine and patient referral.

"Patients do not have the access to doctors that they'd like, and one of the things they really like about self-referring for CT is the ability to actually see a physician face-to-face, and pepper them with ridiculous questions for 20 minutes because they're paying out of pocket," Brant-Zawadzki said. "People distrust their managed care systems because their goals are managed costs and not managed care."

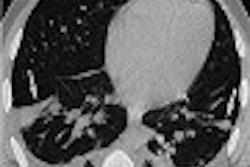

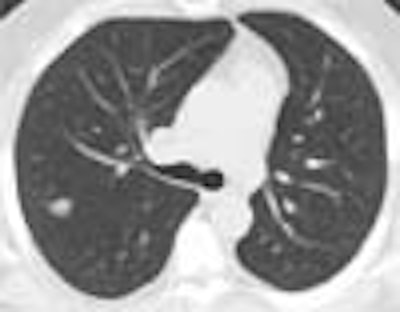

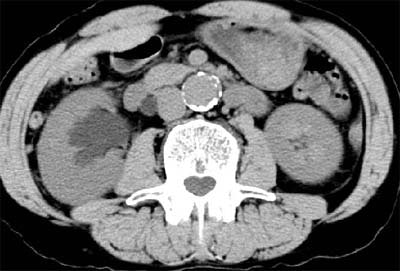

At least a third of his screening clients have HMO coverage, Brant-Zawadzki said, displaying an image of a patient with back pain that had not been prolonged or severe enough to warrant a CT scan from the managed care plan. The diagnosis was hydronephrosis and bladder cancer.

|

| Above and below: Bladder cancer is detected in a 67-year-old male CT screening patient who presented with back pain. Images courtesy of Dr. Michael Brant-Zawadzki. |

|

Physician-ordered diagnostic CT scans have grown from 27 million to 33 million in the U.S., just between 1997 and 2000, Brant-Zawadzki said. CT screening centers have opened by the hundreds. On the military front, former Army surgeon general Dr. Ronald Blanck had sought to provide full-body scans to all his troops. Even the Los Angeles Police Department has subsidized whole-body screening for its officers.

What's more, the healthcare industry has pushed patients to be more self-reliant, he said. The public has wide access to information and suggested treatments, especially over the Internet. Pharmaceutical companies have successfully promoted drugs on TV, and with direct patient marketing. Over-the-counter medicines and health-food stores vie for billions of consumer dollars.

So while consumerism may not be the best approach, economics have made it a powerful one. In the U.S., out-of-pocket spending on alternative methods of care grew from $13 billion in 1993 to $50 billion in the late 1990s, he said.

"Clearly there's a big target here because there are 119 million people aged 40 and over, and 74 million people aged 50 and over in the U.S. Needless to say, the entrepreneurial eyes get wider when those numbers come up."

Professional healthcare organizations and the government have also done their part to whet the consumer's appetite for information -- and for access to just about every kind of screening exam except whole-body CT.

Growing numbers of people are following official recommendations for periodic screening of all kinds, Brant-Zawadzki said. Women are encouraged to self-refer for mammography and pap smears. The middle-aged are told to have colonoscopies, sigmoidoscopies, chest x-rays, glucose tests, dental checkups. They're encouraged by various entities to screen periodically for everything from high blood pressure to hypercholesterolemia.

"So as much as we would like to have a national health strategy for health maintenance, the reality is that the culture is against us," Brant-Zawadzki said. "In fact, (today's reality) is the monument to the managed-care patient."

Criticism and response

Be that as it may, whole-body CT has no shortage of detractors, including the Food and Drug Administration and the Reston, VA-based American College of Radiology. These groups say the procedure could waste time and money by detecting harmless abnormalities, or by finding indolent disease that would never have harmed the patient if left alone.

Detecting such abnormalities can lead to needless patient fear and successive waves of new tests, critics warn, each with its own costs and risks to the patient. At some point, tests might be ordered less for their medical significance than to allay patient fears, or even to soothe doctors' qualms about liability.

Then there are concerns about radiation dose in whole-body CT screening, and about the explosion of findings that is occurring as a result of more screening exams provided on powerful new scanners.

Turning first to radiation concerns, Brant-Zawadzki cited an ACR document, Radiation risk: a primer (1996). The paper states that radiation risk data, extrapolated from atomic bomb survivors exposed to high radiation doses, are valid only as "'crude first-order approximations'" of radiation's effects, and cannot be extrapolated to calculate the carcinogenicity of low-dose events.

The significance of incidental findings, which varies widely, can be determined by assessing them individually, he said.

"You use your common sense, the same thing that primary care physicians do in their offices when they come across a finding," Brant-Zawadzki said. "Medicine is an art. We're trying to make it a science, but it's still an art."

And while individuals may fear bad news, reality testing -- that is, diagnostics that prove or disprove one's fears -- is an excellent antidote, he said, adding that people are afraid long before they sign up for whole-body CT. Even fears resulting from adverse findings can often be eliminated with more reality testing.

"There are few more rewarding experiences than spending a day at a screening facility," Brant-Zawadzki said. "Patients are enthused, they're very grateful for the study even when it's positive, they like the easy access to information..... I'm actually in favor of having people self-refer, because silent and clinically occult disease is widely prevalent -- heart disease being at the top, followed by cancer."

The heart

"We know that plaque burden is much greater than currently estimated by catheter angiography," Brant-Zawadzki said. "We know that remodeling may be related to (plaque) vulnerability, hence catheter angiography underestimates plaque burden. We know that traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors are incomplete in predicting (coronary) events."

According to the Framingham risk factors, 50% of individuals with acute myocardial infarction have normal cholesterol profiles, Brant-Zawadzki said. Sudden death is the first sign of coronary vascular disease in more than 150,000 people a year.

Coronary calcium isn't present in the normal heart, and it's very amenable to CT detection, Brant-Zawadzki said. Studies in asymptomatic individuals with coronary calcium and elevated cholesterol have shown that intervention lowers the risk of coronary events.

The lungs

A recent study in Japan followed 802 Japanese patients with stage 1A lung cancer who did not undergo surgery, Brant-Zawadzki said. For these patients, survival was 16.6% at five years, and 7% at 10 years (Lung Cancer, Vol. 36:1, pp. 65-69).

"These people die," he said. "And yes, there are a few indolent cancers. And it's a fact that there are some survivors of stage 1A lung cancer; however, the (survival) rate is low."

As for incidental findings, Brant-Zawadzki is convinced that overdiagnosis bias doesn't exist. Data from the Early Lung Cancer Action Project (ELCAP) showed that CT screening of 817 asymptomatic smokers produced very low numbers of unnecessary biopsies, as long as size and shape criteria were used to select which nodules were candidates for biopsy, he said. Forty-three of the subjects had noncalcified nodules detected by CT, but out of 123 nodules that met the criteria for biopsy, just 15 were found to be benign (The Lancet, Jul 10, 1999, Vol. 354:9173, pp. 99-105).

Dr. Claudia Henschke and colleagues from Cornell University in New York City have estimated the cost of CT lung cancer screening at $2,500 per life year saved, Brant-Zawadzki said. That makes lung screening far more cost-effective than mammography, estimated at $30,000 per life-year saved, and colorectal cancer screening, estimated at $50,000 per life-year saved.

Mayo Clinic study

An ongoing lung screening study at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, has examined 1,520 asymptomatic current (61%) and former (39%) smokers using thin-section spiral CT. The study doesn't address whole-body screening per se, but adds abdominal scanning to the standard thoracic protocol, thereby expanding the scope of previous trials by including nonpulmonary thoracic incidental findings. Dr. Geoffrey Rubin from Stanford University offered the Mayo Clinic trial statistics in a presentation immediately preceding Dr. Brant-Zawadzki's.

The three-year study, led by Dr. Steve Swensen and colleagues, has so far yielded 696 findings that the researchers deemed clinically significant. Of these, 235 were found in the abdomen. There were 117 abnormal vascular findings, including 51 abdominal aortic aneurysms. Forty-one lung cancers were detected, 59% of which were early-stage. There were also 63 indeterminate renal masses, 21 indeterminate hepatic masses, pancreatic cancers, ovarian cancers, lymphomas, and one spinal metastasis, Rubin reported.

In all, 79% of the patients had one or more positive findings that required further testing or intervention. Of these, 9% had indeterminate masses, 3.6% had documented neoplasia, and 0.6% had documented abdominal neoplasia.

At his screening center, Brant-Zawadzki said he has found abnormalities in a third of his clients, not including those in whom coronary calcium has been detected. Forty-three percent of the abnormalities are pulmonary nodules; cancer has been found in about 1% of the clients. The screening group is a cross-section of individuals over 40, not a high-risk smoker population, he said.

The regulators

Brant-Zawadzki also discussed the statements of radiology's regulators, who urge potential patients to avoid whole-body CT screening pending further study.

In its "Statement on Total Body CT Scanning," for example, the ACR cautions that there is no evidence that whole-body CT screening prolongs life. The exam, it said, could even lead to the discovery of "numerous findings that will not ultimately affect patients' health, but will result in increased patient anxiety, unnecessary follow-up examinations and treatments, and wasted expense."

The FDA statement goes even further. In its discussion of CT Whole Body Scanning, the agency explains that "if the CT exam is interpreted as abnormal, either the abnormal interpretation is incorrect, or you may have nothing significant wrong with you, or you may have a life-threatening disease for which there may or may not be a cure.... In any case, it is unlikely that CT screening will benefit an individual lacking signs or symptoms of disease by detecting a serious disease early enough to treat it and alter the outcome significantly."

"As radiologists, we can all just pack up and go home," Brant-Zawadzki quipped. "What does that say about doctor-referred CT scans for people who have symptoms? Because if this is what the FDA thinks is true about detecting disease in a presymptomatic stage, guess what they think about the value of CT in the post-symptomatic stage."

To be sure, these organizations seek to warn people that whole-body CT isn't a panacea -- not to indict the practice of radiology. Brant-Zawadzki said he was even asked to review the FDA statement before it was published.

But official statements on whole-body CT screening differ markedly from those associated with other screening exams, wherein early detection is just what the doctor ordered. An ACR statement on screening mammography, for example, holds that "the earlier breast cancers are detected, the better are the chances for improved treatment results."

Conclusions

In the end, market forces and cultural demands will prove more powerful than healthcare policy makers, and whole-body CT will find its place, Brant-Zawadzki predicted. He quoted from a recent article by James Robinson, Ph.D., entitled "The End of Managed Care:"

"'By default if not design, the consumer is emerging as the locus of priority-setting in healthcare. The shift to consumerism is driven by widespread skepticism of governmental, corporate, and professional dominance, economic prosperity, and Internet technology with access to information.

If the right thing for healthcare is defined as an approach without potential problems of equity, efficiency, and clinical quality, then consumerism fails the test. All other candidates for setting priorities and managing care, including government, employers, insurers and physicians, also fail the test.

But if the right thing is defined as the approach most compatible with the nation's social culture and political institutions -- the candidate that remains standing after all other constants are vanquished -- then consumerism is not only the likely but indeed the right thing for U.S. healthcare'" (JAMA, May 23-30, 2001, Vol. 285:20, pp. 2622-2628).

"Do I think that's good? No," Brant-Zawadzki said. "Do I think it's real? Yes. Indeed ladies and gentlemen, culture eats strategy for lunch."

By Eric BarnesAuntMinnie.com staff writer

October 2, 2002

Stanford Radiology offers online CME at http://radiologycme.stanford.edu.

Related Reading

Following up incidental findings may do more harm than good, September 5, 2002

Whole-body MR may be feasible for tumor staging, August 28, 2002

Pennsylvania takes hard line on self-referral CT screening, May 31, 2002

Experts weigh benefits, drawbacks of whole-body CT, May 2, 2002

CT sees growth, and new concerns over radiation dose, November 25, 2001

For the person who has everything, whole-body CT makes inroads, September 11, 2001

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com