The H1N1 flu virus is hitting population centers faster and harder than some had predicted. It's become clear that coping with the infections will take more than an ample supply of vaccine, though that piece will be crucial. Minimizing the mortality associated with swine flu will require creative use of a variety of tools to assess the disease and its severity.

For that task, chest CT is emerging as a useful modality, both to confirm H1N1 diagnosis when other tests are equivocal and, as shown in a new study, to assess lung damage in the most seriously ill patients.

Researchers studying CT scans have found that patients with severe cases of the H1N1 virus are at risk for developing severe complications, including pulmonary emboli (PE), according to a study published online in the American Journal of Roentgenology. PE was seen most frequently among obese H1N1 patients.

Pulmonary embolism occurs when one or more arteries in the lungs become blocked. Aggressive treatment with anticoagulants can reduce the risk of death.

The clinical manifestations of H1N1 disease include flulike symptoms such as fever, cough, sore throat, body aches, headaches, chills, and fatigue, and in some cases vomiting and/or diarrhea have been reported, wrote Dr. Prachi Agarwal and colleagues from the University of Michigan Health Services in Ann Arbor.

"With the upcoming influenza season in the U.S., knowledge of the radiographic features of S-OIV (H1N1) is important, as well as the virus' potential complications," they wrote (AJR online, October 14, 2009).

Of 222 patients identified with S-OIV (H1N1) infection over the three-month study period, 66 who underwent chest x-ray for the detection of H1N1 abnormalities were examined in the study.

Patients were divided into two groups, with group 1 consisting of 14 patients (mean age, 43.5 years) who were severely ill and required admission to the intensive care unit and advanced mechanical ventilation. Group 2 consisted of 52 mostly younger patients (mean age, 22.1 years) who were not severely ill and did not require ICU admission.

A total of 15 patients (10 from the ICU group, and five from the largely outpatient group) underwent thoracic CT scans. Of these, 11 were performed specifically for evaluation of PE and 13/15 used iodinated contrast (Isovue-300, Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ) at 4 mL/sec along with 1.25-mm collimation on a 64-detector-row scanner (LightSpeed VCT, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, U.K.). The three noncontrast exams performed outside the institution were acquired using 2.5-mm collimation, the authors wrote.

All images were examined by two experienced thoracic radiologists.

|

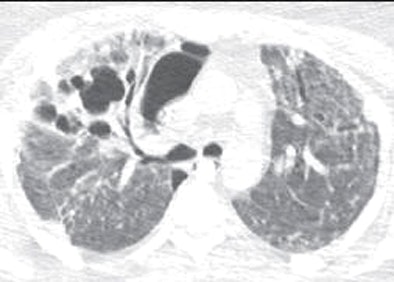

| Thirty-three-year-old woman with laboratory-confirmed S-OIV (H1N1) requiring extracorporeal life support. Pseudomonas infection was confirmed on subsequent bronchoalveolar lavage. Follow-up CT 41 days after onset of clinical symptoms shows new pneumatoceles in right upper lobe and small medially loculated right pneumothorax. Patient had two prior chest CTs done on days 5 and 21 from onset of illness, which showed perihilar and lower predominant ground-glass opacities, consolidation, and nodularity. Also, segmental and subsegmental pulmonary emboli in lower lobes were noted on second CT on day 21. All images republished with permission of the American Roentgen Ray Society. |

"On the initial chest radiographic images, the lung parenchyma was classified as normal or abnormal," they wrote. "The abnormalities were further characterized as consolidation (opacification obscuring the underlying vessels), ground glass opacity (GGO; increased attenuation without obscuring the underlying vessels), nodules, and reticulation."

Detected lung abnormalities were localized and characterized as predominantly central, peripheral, or diffuse. A chi-square test was used to analyze the extent of radiographic abnormality.

The results showed patchy consolidation (14/28, 50%) as the most common radiographic finding, most commonly in the lower (20/28, 71%) and central lung zones (20/28, 71%), Agarwal and colleagues reported.

All group 1 patients had abnormal initial radiographs as well as extensive disease involving three or more lung zones in 93% (13/14), compared to 9.6% (5/52) of the less seriously ill group 2 patients (p < 0.001). In addition, no group 2 patient had more than 20% overall lung involvement on initial radiographs compared with 93% of group 1 patients (13/14).

"The CT examinations showed a combination of GGO and consolidation in nine subjects, and predominantly GGO in one patient," the authors wrote. Parenchymal abnormalities were diffuse and without zonal predominance in seven patients (70%), and with lower-lung predominance in three.

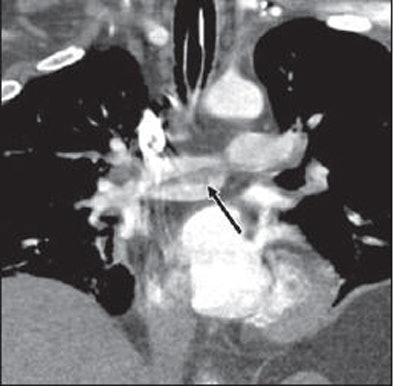

Pulmonary emboli were seen on CT in five of 14 (36%) ICU patients, the authors reported. These included a large saddle embolus straddling the bifurcation of the main pulmonary artery in one patient, which required an interventional procedure for mechanical fragmentation of the embolus.

|

| Twenty-eight-year-old man with laboratory-confirmed S-OIV (H1N1) requiring advanced mechanical ventilation with adverse outcome. Coronal reformatted image from contrast-enhanced chest CT examination shows saddle embolus (arrow) straddling bifurcation of main pulmonary artery. |

Also found at CT were a lobar emboli in one patient, segmental emboli in two patients, and subsegmental emboli in one patient. Two patients had deep venous thombosis in the leg veins at indirect CT venography that was confirmed on ultrasound.

The prevalence of PE was especially high in obese patients, the researchers wrote of a previous report describing the group 1 results.

"There was a high prevalence of obesity: 90% of patients (9/10) had a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30, while 70% (7/10) were extremely obese with a BMI ≥ 40," they wrote. "All 10 patients were reported to have abnormal chest radiographs with bilateral abnormality, five patients had PE, and one patient had isolated deep venous thrombosis."

The most frequent pattern of abnormality in the H1N1 patients is bilateral alveolar disease with lower and central lung preponderance, they wrote. Among the hospitalized patients, the abnormalities progressed to severe air-space disease, and several patients with severe disease developed acute PE during their hospital stay.

The authors cited limitations including the retrospective nature of the study, and the fact that patients were presumed to be positive for H1N1 based on the results of an influenza A test. The results may be biased toward patients with more severe disease on initial radiographs, since that group provided most of the patients who went on to CT, they added.

"Radiographs are normal in more than half of patients with S-OIV (H1N1) infection, but manifest as extensive bilateral air-space disease in hospitalized patients requiring advanced mechanical ventilation," they wrote. "These patients are also at risk for developing PE, which should be carefully sought for on contrast-enhanced CT scans."

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

October 21, 2009

CT can aid early swine flu diagnosis, October 14, 2009

Virus outbreaks put scrutiny on infection control practices, August 10, 2009

Pulmonary CTA finds more than pulmonary embolism in children, August 25, 2009

CT protocols reduce risk for pulmonary embolism, March 9, 2009

11 steps for preventing MRSA infections in MRI, November 6, 2008

Copyright © 2009 AuntMinnie.com