Low-risk patients who tested positive at coronary CT angiography (CTA) ended up getting more prescriptions for cholesterol-lowering drugs and aspirin, signs of good preventive care. But they also got more stress tests, nuclear medicine scans, and cardiac cath procedures, than a control group, researchers found in a May 23 study in the Archives of Internal Medicine.

And despite all the tests and procedures in the scanned group, the study found no difference in cardiac events at 90 days or at 18 months between those who received coronary CTA versus a group of similar individuals who did not have the scans -- though the single event in the nonscreened group was a fatal heart attack.

The findings suggest that current indications discouraging the use of coronary CTA in low-risk populations may be the right stance for now, wrote the authors from Johns Hopkins University and Seoul National University.

At least in the short term, patients don't appear to benefit from knowing whether or not coronary artery plaque has been detected using coronary CTA, said lead author Dr. John McEvoy in a statement accompanying release of the study. "However, their physicians may be inclined to be more aggressive with prescriptions or follow-up tests," he said.

"While coronary calcium scanning remains an important adjunct for cardiovascular risk screening and improved compliance with statins, cardiac CT angiography needs more validation in asymptomatic cohorts before use as a screening test," commented Dr. Matthew Budoff, a professor of medicine at the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute, in an email to AuntMinnie.com. Budoff was not associated with the study.

The study compared two similar groups of patients from a health-screening program: one group was scanned with coronary CTA and the other was not scanned. The two groups were followed prospectively for 18 months.

It was among the first research efforts to assess the implications of coronary CTA in a large matched cohort, including its effect on physician prescribing practices and patient use of medications, the authors wrote.

"Given the potential for more widespread use of [coronary] CTA in cardiac risk evaluation, we sought to evaluate the downstream implications of CCTA testing," wrote McEvoy, along with co-authors including Dr. Michael Blaha and Dr. Khurram Nasir (Archives of Internal Medicine, May 23, 2011).

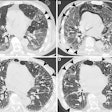

The study compared results in 1,000 asymptomatic patients in the coronary CTA group, scanned in 2005 and 2006, with 1,000 matched controls (mean age, 50 ± 9 years). The scanned subjects underwent retrospectively gated coronary CTA on a 64-detector-row scanner (Brilliance, Philips Healthcare) using 0.625-mm collimation, 120 kVp, and 800 mAs tube current following injection of 80 mL iodinated contrast. Scans were examined independently by experienced readers blinded to the clinical results.

The patients were followed up at 90 days and at 18 months following the initial scan. Data regarding medications, secondary scans, and revascularization procedures were obtained from medical records and telephone contact with the patient using structured questionnaires. Patients were assessed for medication use, test referrals, and cardiovascular deaths.

In all, 21% (n = 215) of the 1,000 scanned patients were found to have coronary atherosclerosis and were defined as CTA positive, while 79% were negative. Among the 215 positive patients, plaque was seen in 392 segments. Fifty-two (5%) of these had significant (≥ 50%) stenosis and 21 (2%) had severe (≥ 75%) stenosis.

Medication use at 90 days, 18 months

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Odds ratios for statin and aspirin use in the CTA-positive group at 18 months were 3.3 (95% confidence interval: 1.3-8.3) and 4.2 (95% confidence interval: 1.8-9.6), respectively. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

No. of secondary tests and revascularizations

|

Statins were prescribed more often in patients with positive coronary CTA results, compared with the control group (p < 0.001), and the difference persisted when patients were stratified by National Cholesterol Education Program risk categories. Patients with a negative coronary CTA were less likely than controls to receive a statin prescription.

After 18 months, the patients with plaque detected on the test were 10 times more likely to have been sent for an exercise stress test, a nuclear medicine scan, or a cardiac catheterization, compared with those patients who didn't undergo CTA. Also, they were three times more likely to be taking a statin medication, and four times more likely to be on aspirin therapy.

Baseline aspirin use was not significantly different between the screened and nonscreened group. However, patients later found to have positive results at coronary CTA had greater aspirin use than control patients (13% versus 6%, p < 0.001). And those with abnormal CTA more frequently had aspirin prescribed at the initial visit.

Referral for secondary tests was more common in the total CTA group than in the controls at 90 days (5.5% versus 2.2%, p < 0.001). In fact, just 1.4% of those with normal CTA scans were referred for secondary tests during the follow-up period, versus 21% of those with positive coronary CTA results.

A total of 13 patients in the scanned group had revascularization procedures within 90 days, versus one without a scan.

No cardiac events were found in the first 90 days in either group; however, there was one hospital admission for unstable angina in the scanned group, and one unspecified cardiac death in the control group.

In summary, a positive coronary CTA result was associated with the use of more medications (an effect that lessened over time). In addition, coronary CTA performance was associated with an increase in downstream secondary testing and revascularization procedures, the group reported.

"Thus, the potential benefit of increased medication use in the CCTA group is tempered by the risk of further testing in low-risk patients without any evidence-based indication," the authors wrote.

Whether knowledge of a positive coronary CTA result can influence behavior remains unclear, as the literature is limited and the results are mixed.

The significantly increased rate of secondary test referrals in asymptomatic patients with low Framingham risk of cardiac disease who tested positive at coronary CTA may be due to a variance of the so-called "oculostenotic reflex," an angiographic term referring to stenoses that may appear visually severe but lack clinical significance.

The 2007 Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial showed that aggressive lifestyle changes delivered outcomes similar to those of percutaneous cardiac interventions in patients with stable heart disease.

"[The COURAGE] findings highlight the need to consider the pretest probability of disease before performing imaging tests in patients who may be subsequently exposed to potentially harmful downstream procedures with questionable prognostic benefit," the group wrote.

The current study's main limitations concern the self-selected patient cohort, with its inherent biases, and the use of a homogeneous Korean study cohort, the authors noted.

"The use of CCTA for risk assessment in an asymptomatic population is not currently supported by clinical guidelines and for now remains a research tool," McEvoy and colleagues concluded.