CT-based calcium scoring is a strong predictor of heart attacks in the young and old, not just the typical middle-aged individual at intermediate risk, according to a study presented on Wednesday at the 2011 American Heart Association (AHA) meeting in Orlando, FL.

Looking at data from nearly 6,000 individuals participating in the prospective, population-based Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), researchers from Johns Hopkins University and other institutions found that coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring can be just as useful in a 45-year-old as it is in someone pushing 80. In fact, younger people with higher levels of calcium were found to have more heart attacks than older people without evidence of calcified plaques at CT, they said.

"The concept we're really getting at in the medical community is arterial age rather than chronological age," said Dr. Michael Blaha, a cardiology fellow at Johns Hopkins, in an interview with AuntMinnie.com. "It's important to know how old you are, but it's really more important to know how old your blood vessels are."

Blaha, along with lead author Dr. Rajesh Tota-Maharaj, Dr. Michael Silverman from Johns Hopkins, Dr. Matthew Budoff from the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute, and other colleagues, studied 6,800 MESA participants younger than 54 and older than 74 who had a calcium scoring test without a diagnosis of heart disease, following them for a median period of seven years.

The researchers' ultimate goal is to potentially expand the AHA's IIa recommendation (I is the highest recommendation) for coronary artery calcium scoring currently in place for intermediate-risk patients, having it cover a wider group of asymptomatic individuals who could potentially benefit from CAC scoring, Blaha said.

Currently, intermediate risk is generally defined as "middle-aged adults with one or two risk factors," he said. "What we did was intentionally look at patients who wouldn't be considered intermediate risk -- those who fall outside of the guidelines right now -- including the young and the old, people with zero risk factors, and people with many risk factors." In other words, people outside the usual group of patients for whom this test would be recommended.

All MESA participants with documented CAC scores were included in the study, which had a median follow-up time of 5.8 years. The primary end point was cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, angina, or coronary revascularization.

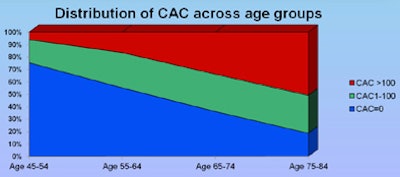

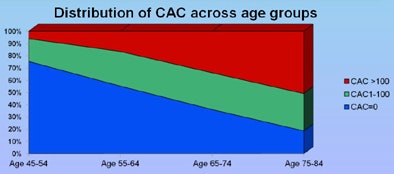

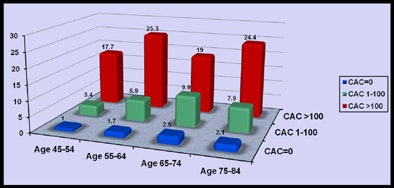

The patient cohort was divided by age group (45-54 years, 55-64 years, 65-74 years, and 75-84 years), while coronary artery calcium was stratified as CAC = 0, CAC = 1-100, and CAC > 100.

Population characteristics were collected at baseline examination and during follow-up phone calls. All cardiovascular events were confirmed with clinical documentation. Within age groups, Cox regression analyses were conducted for increasing CAC scores, and hazard ratios (HR) were calculated and Kaplan-Meier curves constructed to show the risk of death and survival analyses for increasing CAC score within each prespecified age group.

Age is just a number

Among patients ages 45 to 54 years, just 4% had CAC scores greater than 100. However, these patients had an event rate of 17.7 per 1,000 person-years, and they were eight times more likely to have an event related to coronary heart disease than those with calcium scores of 0, Blaha said. As age increased, the percentage of current smokers decreased, while the proportion of hypertensive and diabetic patients increased.

The finding underscores the value of CAC determination in younger persons who may be at an increased risk of coronary heart disease events, and may have significant atherosclerotic burden even if they're asymptomatic, Blaha said.

"If you're young and have calcium, you're at high risk, and if you're old and you have no calcium, just because you're old doesn't mean you're at high risk," he said. "What matters is if you have atherosclerosis."

In the 75- to 84-year-old group, calcium remains an inaccurate means of improving cardiovascular risk stratification, he said.

"If you're young and have a calcium score greater than 100, your risk far exceeds that of someone older than 75 with no calcium," Blaha said. "About 20% of people in our older group had a calcium score of 0."

|

| All images courtesy of Dr. Michael Blaha and Dr. Rajesh Tota-Maharaj. |

|

| Cardiovascular disease event rate per 1,000 person-years by CAC score and age groups. |

The results show that the calcium scoring test may benefit both younger and older people in terms of refining their true heart disease risk, according to the researchers.

"It can help us identify a subset of younger people at higher risk who should make substantial lifestyle modifications and possibly take cholesterol-lowering medication and aspirin," said Tota-Maharaj. "For older individuals without calcium in their arteries, it means they do not need routinely prescribed cholesterol-lowering medications or aspirin because they are at a lower risk of a heart attack."

"Framingham is a little outdated, and it tends to overestimate risk in nearly all modern populations that are treated with medications," Blaha said. "That's why I think the time has come to incorporate atherosclerosis imaging directly into risk prediction."

Calcium scoring makes an excellent addition because it "applies outside the typical intermediate-risk patient," Blaha said. "It applies to the young and the old, and it applies to those with few risk factors and many risk factors."

Thus, rather than creating a new level of evidence, the study aims to expand the pool of patients for whom level-II evidence already exists, Blaha said.

To eventually achieve a higher level of evidence for risk prediction, the group is currently putting together a multicenter, randomized study of CAC scoring in which 30,000 patients will be assigned to current care (cholesterol, C-reactive protein, stress tests, etc.) versus CAC score, Blaha said.