CHICAGO - Confirming a counterintuitive finding that researchers will need to explore more fully, current long-term smokers showed lower CT measures of emphysema than former smokers in a study presented on Monday at the RSNA meeting.

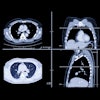

The study of more than 10,000 smokers revealed that current smokers have significantly reduced regions of low attenuation at quantitative CT (QCT) of the chest compared to former smokers. Areas of reduced attenuation (≤ -950 HU) are associated with inflammatory changes in lung parenchyma that characterize emphysema, explained researchers from the Quantitative Imaging Laboratory at National Jewish Health in Denver.

"In a preliminary analysis of sample attenuation [categorized by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease] GOLD stage and smoking status, across all stages of disease severity current smokers do indeed show higher scores for attenuation," said researcher Jordan Zach in his presentation. "Interestingly, while the significance of this [finding] grew substantially as the disease progressed, the relative difference stayed pretty stable -- about 40% to 50% difference on inspiration and about 20% to 25% on expiration."

Earlier studies have shown that that active smoking is associated with lower extent of emphysema as quantified on chest CT. This study aimed to evaluate whether QCT measures of emphysema differ based on current smoking status while controlling for demographic parameters and lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) study subjects.

In the new analysis of the COPDGene study, 10,307 subjects with long-term histories of heavy cigarette smoking underwent spirometry and volumetric CT scans at full inspiration. Of this group, 7,662 current and former smokers (49% former smokers; 54% male; 70% white; mean age, 60 ± 9.1 years; mean body mass index, 28 ± 6) met the criteria for classification under the GOLD system and underwent QCT analysis for the study, Zach said.

Dr. David Lynch, Zach, and colleagues used open-source 3D Slicer software to segment the lung images and perform densitometry, and emphysema was defined as lung tissue with attenuation ≤ -950 HU on inspiratory CT, expressed as a percent of total lung capacity (%LAA-950HU). The effect of smoking status on QCT-derived lung capacity was assessed by multiple linear regression in a model controlled by age, gender, race, height, forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), and total pack-years of smoking history, the group wrote in an abstract.

Fifty-seven percent of current smokers versus 41% of former smokers were classified as controls -- that is, individuals without COPD. The mean LAA-950HU was 3.7 ± 6.5 in current smokers, compared with 10.1 ± 11.8 in former smokers (p < 0.0001). And %LAA-950HU was 40% to 50% lower in current smokers across each GOLD stage, Zach said. As for confounding factors, current smokers were significantly younger than former smokers.

"After adjusting for our multivariate model, our areas of low attenuation were significantly lower for current smokers on both inspiration and expiration -- about 3.7% lower on inspiration and 4.2% lower on expiration," he said.

"The effect was substantially different in the [COPD] cases versus the controls," he said. On inspiration, smokers with COPD were about four points lower than former smokers, while control-group smokers were only about 1% lower. Similarly, on expiratory scans, COPD smokers landed about four points lower than former smokers, while control-group smokers were about 1% lower than former smokers.

So in every category, current smoking status was significantly associated with %LAA-950HU on quantitative chest CT, Zach said, and after adjusting for patient demographics and lung function, current smokers showed significantly lower %LAA-950HU than former smokers.

"We found that low-attenuation areas were substantially lower in current smokers than in former smokers, and again this effect was substantially larger in those with COPD versus those without," Zach said. "This isn't to say that cigarette smoking is somehow a protective effect in COPD, but it certainly is important to know when evaluating low-attenuation areas as QCT measures of COPD severity."

Moving forward, the group is looking to explore the effect more fully and try to understand the mechanisms behind it, he said.

"It seems that pulmonary function decreases rapidly in continuing smokers, but at the same time emphysema measures on QCT remain lower in smokers than in those who quit," he said. More visual analysis and other tests will be performed on the CT scans, and the group will also track patients over time to look at disease progression.

Session moderator Dr. Martine Rémy-Jardin from Hôpital Albert Calmette in Lille, France, said that it will be important to explore the effect of the significant age difference between the older COPD and younger control groups.

"When we get older, we may have an increase in the size of the alveoli, and increased detection of emphysema," she said. "It will be interesting to know if [age] was a confounding factor."