Patients with HIV infection are more prone to potentially dangerous noncalcified coronary plaque than similar uninfected individuals, according to a study that used coronary CT angiography (CCTA). Results were published in the April 1 issue of Annals of Internal Medicine.

In the multicenter study of 1,001 men who underwent coronary calcium assessment, including 759 who also had contrast-enhanced CCTA, HIV-infected men had a greater prevalence and extent of coronary artery plaque than uninfected men.

"We found that men with HIV had more noncalcified plaque; they had a greater prevalence of noncalcified plaque, and a greater extent of plaque ... even after adjusting for traditional cardiovascular risk factors," said principal investigator Dr. Wendy Post in an interview with AuntMinnie.com.

Dr. Wendy Post from Johns Hopkins University.

Dr. Wendy Post from Johns Hopkins University.

Post is a professor of medicine and epidemiology in the cardiology division of Johns Hopkins University. Other participating institutions included the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, the University of Pittsburgh, and Northwestern University (Ann Intern Med, April 1, 2014, Vol. 160:7, pp. 458-467).

Increased cardiovascular risk

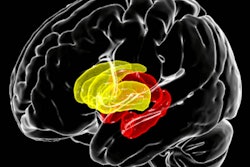

HIV and perhaps antiretroviral therapy are expected to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, but data are conflicting, the authors wrote. The study aimed to evaluate the possible association in a group of HIV-infected and noninfected men -- and CCTA was a perfect tool.

"We looked at coronary CT angiography so we can see not only coronary artery calcium, which is usually done as a screening test without contrast, but [also] more details about the plaque and whether or not it's calcified," Post said. "So this study is unique because it's a large study of CT angiography of men who have sex with men ... who are at risk for HIV."

The research was drawn from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS), an ongoing, prospective study of the natural and treated histories of HIV-1 infection in gay men that began in 1984. The 1,001 men were assessed for coronary artery calcium (CAC), plaque characteristics, and stenosis using noncontrast CT and CCTA at four centers between 2010 and 2013.

CAC scores and CCTA

The researchers used 64-detector-row CT scanners at three centers (GE Healthcare, Siemens Healthcare) and 320-row MDCT (Toshiba Medical Systems) at the fourth center. They used prospective electrocardiogram triggers to minimize radiation exposure, except in a few cases where the heart rate was too fast or irregular. The median CCTA dose was 1.9 mSv, the group reported.

Patients received beta-blockers as needed and sublingual nitroglycerine. All images were transferred to the core reading center (Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute) for review by trained, experienced readers who were blinded to the participants' characteristics and HIV status. The readers evaluated the images based on the 15-segement American Heart Association model.

The cohort, ages 40 to 70 years, included men who were HIV positive (n = 618) and uninfected men (n = 383). Those with contraindications to CT angiography were excluded. The researchers collected data on coronary artery disease risk and clinical variables based on history, physical exams, and blood tests.

About a third of all participants used lipid-lowering therapies. The men who had only noncontrast CAC scans were slightly older, and they had more diabetes and hypertension and lower levels of LDL cholesterol than the group as a whole.

Stenosis in each segment was defined on a five-point scale as follows:

- 0 -- none

- 1 -- 1% to 29% (minimal)

- 2 -- 30% to 49% (mild)

- 3 -- 50% to 69% (moderate)

- 4 -- 70% or greater (severe)

The team also calculated a "segment involvement" score, representing the sum of segments with plaque, Post and colleagues wrote.

More plaque, especially noncalcified

More HIV-infected men than uninfected men (63.3% versus 53.1%) had noncalcified plaque, and the higher prevalence remained after adjusting for age, race, scanning facility, and cohort (prevalence ratio [PR], 1.28; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.13-1.45).

After once again adjusting for age, race, scanning center, and cohort, the men with HIV also had a higher prevalence of CAC (PR, 1.21; 95% CI: 1.08-1.35; p = 0.001) and a higher prevalence of any plaque (PR, 1.14; 95% CI: 1.05-1.24; p < 0.001), the study team reported.

Among those who underwent CCTA, the prevalence of plaque in any coronary segment was 77.6% for HIV-infected men and 74.4% for uninfected men, and the higher prevalence remained after adjusting for age, scanning location, and cohort (PR, 1.28; 95% CI: 1.13-1.45). The prevalence also remained significant after adjusting for additional coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factors (PR, 1.25; 95% CI: 1.10-1.43).

In addition, the prevalence of coronary artery stenosis greater than 50% in any coronary segment was 16.9% among HIV-infected men and 14.6% among uninfected men (PR, 1.48; 95% CI: 1.06-2.07) after adjusting for age, race, scanning center, and cohort; however, this association was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for CAD risk factors, the group wrote.

Mixed plaque was slightly more prevalent in HIV-infected men, but the increased prevalence achieved only borderline significance after being adjusted for coronary artery disease risk factors, the authors wrote. Among men with mixed plaque, the researchers found no association between HIV status and the presence or extent of calcified plaque on CCTA.

"Coronary artery plaque, especially noncalcified plaque, is more prevalent and extensive in HIV-infected men, independent of CAD risk factors," Post and colleagues concluded.

The 618 HIV-infected men were slightly younger and more likely to be African-American than the 383 uninfected men, the researchers noted. Principal limitations of the study were its cross-sectional design and the fact that it only included men.

Longer HIV treatment means more plaque

Another important finding was that men with lower nadir CD4 counts had a higher prevalence of stenosis greater than 50% (p < 0.005), according to Post. "Also, the longer you've been on [highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)], the greater your likelihood of having stenosis" more than 50% (p < 0.007), she said.

This suggests that the differences in plaque extent and composition may partly result from antiretroviral therapy itself. HAART can lead to lipid abnormalities and changes in coronary plaque extent and composition, "especially with the older formulations, which are probably marking people who had been on some of these older drugs," Post said.

Some previous studies, though not all, have also associated low CD4 counts with carotid intima-media thickness and carotid artery plaque, the authors noted. One study showed that continuous use of antiretroviral therapy reduced CAD events compared with interrupted antiretroviral therapy.

Years ago, antiretroviral therapy wasn't routinely initiated as early as it is now, and patients with low CD4 counts weren't treated as aggressively, allowing the disease to progress more rapidly than it does today, Post added.

The greater extent of noncalcified plaque is significant because these plaques may be more prone to rupture, leading to acute coronary syndromes, she said. Still, few coronary events have been seen yet in this cohort, and the authors plan to keep following the patients.

Previous studies have shown that people with HIV have more heart attacks, "but in our study it looks like you can explain that on the basis of more noncalcified plaques," and these are the people who appear to be at greatest risk of events, she said.

"The question is, if we start treating earlier, before the CD4 cell count goes too low, and using newer antiretroviral therapies with fewer side effects, are we less likely to see this increase in risk?" Post said.