Despite high rates of tobacco use, active smokers with HIV do not appear to develop lung cancer at higher rates than the general population. In fact, lung cancer rates seem unusually low, according to a pilot screening study in the June edition of the Journal of Thoracic Oncology.

Just one cancer was found at incident screening, the authors reported. During the follow-up period, 18 deaths (8%) occurred, but none were cancer-related. The study included 224 asymptomatic HIV-infected current and former smokers and 130 HIV-positive patients with known lung cancer.

"Even with the limitation of a small sample size, this is a low rate of lung cancer detection despite our appropriate targeting of a community, epidemiologically, at high risk for lung cancer," wrote Dr. Alicia Hulbert, from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and colleagues.

At higher risk

The diagnosis of one cancer was surprising because the best epidemiological evidence suggests that HIV-positive individuals have up to 2.5-fold higher risk of lung cancer, and 89% of the study cohort were active smokers, the authors wrote. The young age of participants (mean, 48 years) might offer the best explanation for the low yield of lung cancers (J Thorac Oncol, June 2014, Vol. 9:6, pp. 752-759).

HIV-positive smokers are an attractive target for screening because they may be at higher risk for cancer, and there is also concern that with longer life spans due to antiretroviral therapy, lung cancer may become even more common. However, there are no lung cancer data for this population because large CT screening trials, such as the National Lung Screening Trial, routinely exclude HIV-positive participants, the authors wrote.

Also of note, HIV-associated lung cancer has a high case fatality rate, primarily attributed to an advanced stage of disease presentation, the authors wrote. Late lung cancer diagnoses occur even in HIV specialty clinics where patients undergo frequent chest radiographs. More than 80% of the 130 lung cancer patients presenting to the authors' facility had late-stage disease, the group noted.

Hulbert and colleagues aimed to determine the prevalence and incidence of lung cancer in HIV-positive smokers, and they also wanted to assess the feasibility of screening, examining false-positive detection rates.

From 2006 to 2013, they examined 224 HIV-positive smokers with a smoking history of 20 pack-years or more (mean smoking history, 34 pack-years), who underwent low-dose CT at baseline and at the end of the study. Their median age was 48 years, 90% of were black, and 58% had a history of injecting drugs.

Spirometry was performed along with CT at baseline, and participants were evaluated separately for emphysema. Exclusion criteria included a chest CT scan within the previous 18 months, history of lung cancer, or active respiratory infection.

Participants were to be scanned at baseline and annually thereafter for up to four years using a low-dose noncontrast protocol (120 kV, 50-100 mA, 1- to 5-mm axial reconstruction, 0.6-mm collimation) with a 64-detector-row CT scanner (Somatom Sensation 64, Siemens Healthcare). However, of the five possible CT scans for the participants, 8% received just one scan, 46% underwent two scans, 20% received three scans, 17% had four scans, and 9% received five scans. The scans were read independently by two radiologists working in consensus.

In addition to the 224 current and former smokers being screened, Hulbert and colleagues included 130 HIV-infected patients with known lung cancer in the study to determine radiographic markers of cancer risk, they wrote.

Assessing the positive

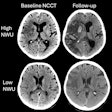

"Due to previous work in evaluating CT changes in HIV patients, we presumed that CT screening would yield a high incidence of inflammatory nodules and scarring from previous pulmonary infections in HIV-positive patients," the authors noted.

As a result, the protocol was designed to allow radiologists to assess noncalcified nodules 4 to 9 mm in diameter as suspicious or nonsuspcious for each patient.

Repeat CT was recommended at three or six months for suspicious nodules smaller than 7 mm, the group wrote. For nodules 10 mm and larger, additional tests could include screening at three or six months, FDG-PET imaging, technetium-99m depreotide scintigraphy, or biopsy. During the follow-up period, the investigators contacted participants twice a year for updates on health status, contact information, and smoking behavior.

One lung cancer -- a stage IIIB non-small cell carcinoma -- was found on incident, first-year screening after baseline, the authors wrote. The patient chose to forego treatment and died four months after diagnosis.

There were no interim diagnoses of lung or extrapulmonary cancer during 678 person-years of follow-up (mean, 3.7 years). None of the nodules detected at baseline in 48 participants were diagnosed as cancer by the end of the study. Most of the 48 nodules were solid; about one-third were ground-glass opacities, and 25% of nodules were larger than 1 cm in diameter. Besides the one lung cancer case, 18 deaths (8%) occurred, but none were cancer-related.

Emphysema across the lung, evaluated separately, was significantly more heterogeneous in HIV-positive subjects with lung cancer, the authors wrote. They analyzed 117 of the 224 screened subjects (without lung cancer), along with 39 of the previously diagnosed HIV-positive lung cancer patients. The standard deviation of voxel intensity corrected for lung air volume was significantly higher in those HIV subjects with lung cancer versus those without lung cancer (p = 0.0001).

Using this group of 117 screening patients and 39 known lung cancer patients, the researchers performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine clinical and radiographic risk factors associated with lung cancer in HIV-positive individuals. The analysis showed that increased age, more pack-years of smoking, lower CD4 count, and increased heterogeneity of emphysema at CT were all associated with lung cancer.

| Characteristics associated with lung cancer diagnosis | ||

| Characteristics | Odds ratio | p-value |

| Increasing age | 1.08 | 0.02 |

| Increasing pack-years | 1.09 | < 0.0001 |

| Decreasing CD4 nadir | 1.006 | 0.006 |

| Increasing standard deviation (SD)/total lung volume (TLV) | 1.23 | 0.02 |

Because the pilot study yielded only one lung cancer diagnosis, any large-scale screening study should be approached with caution, the authors wrote. Factors that might tilt the bias against screening include overdiagnosis, competing causes of mortality over time, more aggressive cancer types, and faster interval progression of cancers, as well as financial burdens, personal anxieties, and potential morbidity due to the workup of false-positives.

"At the very minimum, we believe that until the median age of HIV smokers increases, the rate of detection by helical CT of HIV-associated lung cancers will remain low," they wrote." Advanced age and longer exposure to smoking are strong risk factors for lung cancer, and most screening studies don't screen patients younger than age 55.

"Our identification of biologic and radiographic markers in HIV smokers to define an even higher subpopulation of high-risk individuals may allow algorithms to determine lung cancer risk more effectively, individualize the frequency of subsequent scans, reduce false positives, and limit the costs of future trials," they wrote. In favor of screening is the fact that the U.S. has a large population of HIV-positive smokers older than 55.

"However, for such a study to be feasible in an urban American HIV cohort plagued by polysubstance abuse, considerable measures to ensure patient compliance, adherence, and smoking cessation must also ensue," the group concluded.