CHICAGO - People with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are very likely to harbor high-risk atherosclerotic plaque as well, creating a double health hit that may have a common origin, researchers from Boston reported at RSNA 2014.

The study of more than 400 patients found that over 40% had evidence of NAFLD, and these individuals were three times as likely to have evidence of high-risk plaque, according to the group from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). The association was independent of the severity of atherosclerosis or plaque burden.

Dr. Stefan Puchner from MGH.

Dr. Stefan Puchner from MGH."The association between NAFLD and high-risk plaque was independent of cardiovascular risk factors and the extent and severity of coronary artery disease," said Dr. Stefan Puchner from MGH in his Wednesday presentation.

Previous studies have shown that NAFLD is associated with atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease, he said. A small, single-center study reported an association between high-risk coronary plaque and NAFLD that was independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

CT is ideally suited for characterizing and diagnosing both conditions, which share common cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, Puchner explained.

The study aimed to determine the association of NAFLD with the presence of advanced high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaque as assessed by coronary CT angiography (CCTA).

The cohort of 445 patients was drawn from 1,000 participants in the Rule Out Myocardial Infarction Using Computer-Assisted Tomography (ROMICAT) II trial, half of whom had undergone coronary CTA, and all of whom had a coronary artery calcium scan. The MGH study by Puchner, Dr. Michael Lu, Dr. Maros Ferencik, PhD, and colleagues included only those ROMICAT II patients who had undergone CCTA exams that achieved high image quality, excluding patients with a history of alcohol use or liver disease.

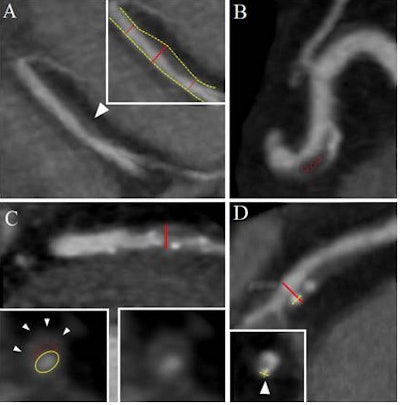

Readers examined the CCTA images for atherosclerotic plaque, significant stenosis (≥ 50%), and features of high-risk plaque, including positive remodeling, low (< 30) HU plaque, napkin-ring sign, and spotty calcium distribution less than 3 mm in all planes.

Positive remodeling was defined using the threshold of 1.1 for the maximal diameter of the vessel at the plaque over the diameter of the proximal and distal normal vessel reference (A). Low HU plaque consisted of the mean HU number within three regions of interest less than 30 HU (B). The napkin-ring sign is a ringlike peripheral higher attenuation surrounding a central core of low attenuation of a noncalcified coronary plaque (C). Spotty calcium was defined as calcified plaque with a maximum diameter less than 3 mm in any direction, length of the calcification less than 1.5 times the vessel diameter, and width of the calcification less than two-thirds of the vessel diameter (D). Image courtesy of Dr. Stefan Puchner.

Positive remodeling was defined using the threshold of 1.1 for the maximal diameter of the vessel at the plaque over the diameter of the proximal and distal normal vessel reference (A). Low HU plaque consisted of the mean HU number within three regions of interest less than 30 HU (B). The napkin-ring sign is a ringlike peripheral higher attenuation surrounding a central core of low attenuation of a noncalcified coronary plaque (C). Spotty calcium was defined as calcified plaque with a maximum diameter less than 3 mm in any direction, length of the calcification less than 1.5 times the vessel diameter, and width of the calcification less than two-thirds of the vessel diameter (D). Image courtesy of Dr. Stefan Puchner.NAFLD was defined as the presence of hepatic steatosis on noncontrast CT without evidence of clinical liver disease, liver cirrhosis, and alcohol abuse, Puchner said.

Patients with NAFLD were more likely to be older than patients without NAFLD (56.2 versus 52.2 years), male (54% female versus 35%), and have a higher body mass index (33 versus 28.8). NAFLD patients were also more likely to have cardiovascular risk factors such as arterial hypertension, diabetes, and dislipidemia, and they were more often a current or former smoker and had a higher calcium score (all p < 0.001, except for body mass index at p = 0.002).

"Patients with NAFLD had almost a six times higher risk of having high-risk plaque features (59.3% versus 19.0%)," according to Puchner.

In univariable and multivariable analyses, the association between NAFLD and the presence of high-risk plaque (odds ratio, 2.21; 95% confidence interval: 1.26-3.87) remained even after adjusting for the extent and severity of coronary atherosclerosis and traditional risk factors.

"These results suggest a potential pathophysiological relationship between NAFLD and high-risk coronary plaque, potentially related to systemic inflammation," Puchner said.

A moderator asked if the group had looked at biomarkers of disease such as low- and high-density lipoproteins and liver enzymes for clues to a potential common etiology between the diseases.

"We believe these pathologies are somehow connected through systemic inflammation," Puchner said. However, biomarkers weren't the primary focus when the retrospective study was designed, so neither that information nor information on drug use was available to the investigators.

Another potential study limitation was the self-reporting of alcohol use, creating the potential for underreporting, he said.