Computer-aided detection (CAD) can only enhance performance if used correctly, and does not reduce the need for training, experts agree. Furthermore, CAD is moving away from pure detection to clinical decision support, but the adoption of new reading paradigms for the screening scenario and improvements in how the technology presents results and are both vital if it is to become an essential imaging tool.

Dr. Stuart Taylor from London.

Dr. Stuart Taylor from London.CAD for colonography has shown particular promise, and most radiologists will come across it in their workflow and will need to understand sensitivity and specificity issues, as well as when CAD should be deployed in this area. The technique's major diagnostic benefits are in small 6- to 9-mm polyps, which often are difficult for the radiologist to spot.

"CAD acts like a spell-check for small polyps," said Dr. Stuart Taylor, professor of medical imaging and consultant gastrointestinal radiologist at University College London, in an interview ahead of the congress. "There are also instances when tumors and large polyps are missed by the radiologist before CAD draws attention to them."

However, he is keen to highlight that CAD is not 100% accurate, nor does it obviate the need for training in CT colonography interpretation.

"The idea that doctors will not need to read as many validated cases to train themselves is incorrect, particularly in the detection of unusually shaped lesions, which is when the radiologist's own eyes and knowledge will pay off," Taylor noted. "An untrained doctor may think a strange shape marked by CAD is too irregular to be a polyp and dismiss it as either a fold or retained faecal residue. In some cases, missing a real lesion like this can have dramatic consequences for the patient as a missed polyp may be, or can become, cancerous."

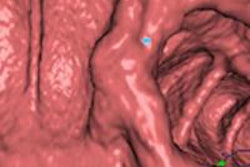

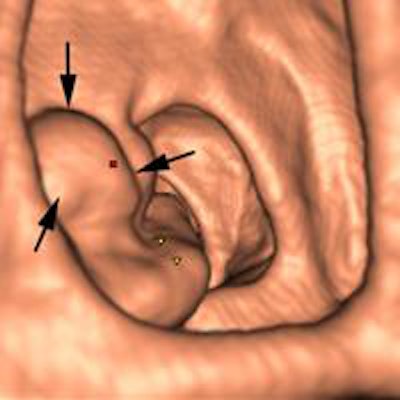

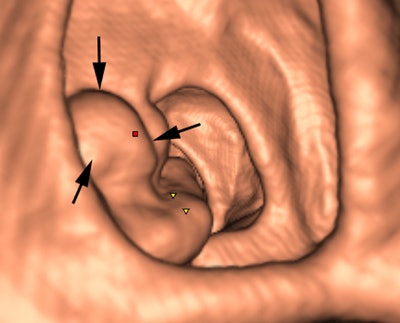

Above: 3D endoluminal image of the ascending colon demonstrates an irregular polypoidal lesion (arrows) correctly identified by CAD. In a reader study, this lesion was initially missed and only detected using second-read CAD by two of 10 readers. Below: Coronal CT colonographic image of the rectum demonstrates a CAD false positive. The CAD (red mark) has incorrectly marked a normal rectal vein (arrows). Images courtesy of Dr. Stuart Taylor.

Above: 3D endoluminal image of the ascending colon demonstrates an irregular polypoidal lesion (arrows) correctly identified by CAD. In a reader study, this lesion was initially missed and only detected using second-read CAD by two of 10 readers. Below: Coronal CT colonographic image of the rectum demonstrates a CAD false positive. The CAD (red mark) has incorrectly marked a normal rectal vein (arrows). Images courtesy of Dr. Stuart Taylor.False negatives can present a challenge too. Typically the computer program looks for the rounded bowler-hat contours of a polyp that stand proud of the bowel wall. It may miss the flatter polyps and even large mass-like lesions that don't have typical rounded contours.

Most manufacturers are further developing CAD using validated CT colonography cases containing examples of unusually shaped flat lesions and also cancers, writing these characteristics into their software and training their programs to recognize them. The diagnostic capacity of CAD is, therefore, continually improving.

CAD advances may also have a positive impact on patients with regard to full-bowel preparation prior to the procedure.

"Refinements in software mean that the CAD programs will increasingly be able to differentiate retained stool from real lesions, due to the increased attenuation of residue following the use of oral iodinated tagging agents. This should mean CAD will work better after reduced or nonlaxative preparation so that patients will no longer have to take unpleasant bowel preparation before CT colonography," Taylor said.

Evidence suggests that second-read CAD is more effective in increasing sensitivity but adds to reporting time, he explained. "Conversely, while concurrent reading may take less time, radiologists can be tempted to only look at CAD marks, which may distract them from scrutinizing nonprompted parts of the colon where there may be lesions."

A large multicentre Italian screening study has pointed to greater time efficiency of using double-reading first-reader CAD (DR FR CAD). CAD initially reads the image, and this first interpretation is around 90% sensitive. Then the radiologist looks at the image with a primary 2D read. In experienced hands, this double-reading paradigm works well and leads to fast and accurate reporting, according to the project's emerging data (Radiology, September 2013, Vol. 268:3).

"If CT colonography is implemented as a population screening test, there will be very large numbers of datasets to read by a relatively small number of trained radiologists. Implementing CAD in a DR FR CAD paradigm may allow the reading of large case numbers in a limited time," Taylor said.

At today's update session, delegates also heard how the mass screening programs of the 1980s are now moving toward an individualized screening dynamic. For this to become optimal, any CAD tool needs to factor in risk constellation and point the radiologist to the best imaging studies for the patient, according to Dr. Ulrich Bick, professor of radiology and vice chair of the radiology department at the Charité university hospital in Berlin.

"Traditional CAD doesn't take into account risk factors such as age or genetics. This combined with its 98% sensitivity for finding microcalcifications means that the radiologist must decide whether or not the often numerous findings are clinically relevant," said Bick, who presented an update on breast CAD at today's session.

![A 68-year-old asymptomatic woman underwent routine mammographic screening (above). A subtle small spiculated mass was correctly detected by CAD in the upper-outer quadrant of the right breast, best seen on the mediolateral oblique (MLO) view (below). Percutaneous biopsy and subsequent surgical excision confirmed a 10-mm well-differentiated, lymph-node-negative invasive ductal cancer in the right breast [pT1b pN0 (sn) G1], which had an excellent prognosis due to its early detection through mammography screening. Images courtesy of Dr. Ulrich Bick.](https://img.auntminnie.com/files/base/smg/all/image/2015/03/am.2015_03_06_00_09_16_89_2015_03_06_CAD3.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) A 68-year-old asymptomatic woman underwent routine mammographic screening (above). A subtle small spiculated mass was correctly detected by CAD in the upper-outer quadrant of the right breast, best seen on the mediolateral oblique (MLO) view (below). Percutaneous biopsy and subsequent surgical excision confirmed a 10-mm well-differentiated, lymph-node-negative invasive ductal cancer in the right breast [pT1b pN0 (sn) G1], which had an excellent prognosis due to its early detection through mammography screening. Images courtesy of Dr. Ulrich Bick.

A 68-year-old asymptomatic woman underwent routine mammographic screening (above). A subtle small spiculated mass was correctly detected by CAD in the upper-outer quadrant of the right breast, best seen on the mediolateral oblique (MLO) view (below). Percutaneous biopsy and subsequent surgical excision confirmed a 10-mm well-differentiated, lymph-node-negative invasive ductal cancer in the right breast [pT1b pN0 (sn) G1], which had an excellent prognosis due to its early detection through mammography screening. Images courtesy of Dr. Ulrich Bick.Results from the European breast cancer diagnosis project, HAMAM, which uses CAD in a more patient-tailored approach, are promising. The project integrates MRI, mammography, and ultrasound with risk factors such as age and gene mutation carrier information. Some risk factors, such as breast density and composition, can even be extracted and factored into CAD's findings.

"For example, CAD could distinguish that four calcifications clustered together in a young patient with dense breasts are more likely to be relevant than in a 70-year-old with low-density fatty breasts," Bick noted. "At present the commercial application of CAD is in pure detection. However, the research points to integrating different modalities, risk factors, and detection into a clinical decision aid."

For the moment, some of CAD's advantages are clear-cut: e.g., finding microcalcifications is tedious for the reader, as the image needs to be checked in quadrants due to resolution issues. CAD, however, speeds up the process by looking at the full image in full resolution and pointing to these microcalcifications. This frees up the human reader to concentrate on other areas such as density, masses and architectural distortions for which the computer is less trained. However, with CAD's average of one false prompt per case, time still risks being wasted on recalls, which in a screening program should not exceed 5% for a human reader.

"I believe that CAD should be used routinely, but it is vital for the radiologists to make the right call between real and false prompts. In a screening situation two radiologists may go through 250 cases in two-and-a-half hours. Things may be missed if there isn't thorough training and a different way for computers to present results," he explained.

With optimizing CAD prompts in mind, Bick pointed to a Dutch project that uses interactive decision support instead of traditional CAD prompts. The reader points to an area of uncertainty, and the computer either concurs with concerns through placing a marker or does not. Such selective interactive prompting has yielded better results than traditional prompting, according to the study by Rianne Hupse, et al.

"Using this paradigm, the computer acts like a sharp-sighted assistant but only in response to the expert's request for feedback," Bick said. "We are interested in this work particularly as in one study, 29 radiologists each reading 300 mammograms from a large database of mammography found only marginal benefit from using traditional CAD. Everyone realizes that the way that traditional prompting works is not best suited to radiologists or to the screening scenario."

Originally published in ECR Today on 6 March 2015.

Copyright © 2015 European Society of Radiology