When Thomas Manning underwent one of the world's first successful penis transplant operations last month, imaging was there to guide the physician team with three separate modalities, according to doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston.

Manning, a 64-year-old bank courier from Halifax, MA, had lost the original organ due to penile cancer that followed a devastating injury on the job that crushed his genitals. The new one came from a cadaver.

Recovering patient Thomas Manning with nurse practitioner Heather Park of MGH Plastic Surgery. Image courtesy of MGH.

Recovering patient Thomas Manning with nurse practitioner Heather Park of MGH Plastic Surgery. Image courtesy of MGH.Now Manning is telling his story openly in what he calls an effort to help remove the shame and stigma surrounding genital injury and disease, conditions that have spiked in recent years due to war and injury. Manning wants others to know that hope of a normal life is becoming a possibility.

"Don't hide behind a rock," he told reporters last week from his hospital room.

Imaging is essential

Individuals who have lost their penises to disease, injuries in combat, or some other type of traumatic event also have to cope with the psychological aspects of such injuries, which can be overwhelming. The hope of offering better long-term outcomes has been the motivation driving research at MGH, the hospital said in a statement.

The highly complex transplant operation, known as a genitourinary vascularized composite allograft (GUVCA), involves surgically grafting the complex microvascular and neural structures of the donor organ onto like structures on the recipient. GUVCA benefits in important ways from the use of imaging, said MGH radiologist Dr. Richard Choi in an interview with AuntMinnie.com.

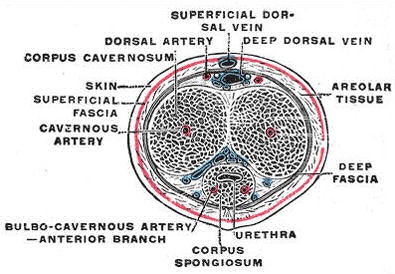

The penis in transverse section, showing the blood vessels. Gray's Anatomy, 1918.

The penis in transverse section, showing the blood vessels. Gray's Anatomy, 1918.The early success in this case "points to the fact that imaging has value, and the surgeons need collaborators to help guide them in this type of procedure," Choi said. The leading imaging modality is CT angiography (CTA), which is performed pre- and postsurgically.

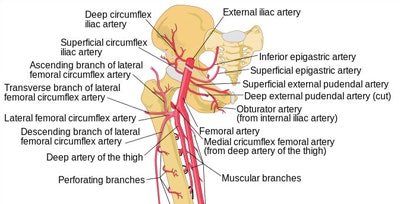

"It's the CTA that identifies the branches of the internal iliac artery, which then feed the pudendal arteries, which in turn feed the arteries supplying the penis," he said.

The same arteries that eventually supply blood to the leg bifurcate in the pelvic region to supply the rectum, testicles, and penis first, he said. To supply the organ, the surgeon needs to choose the vessel side with the best blood supply, which depends on native anatomy and can be affected by age, injury, and the presence of foreign objects such as shrapnel.

Shema of arteries arising from the iliac and femoral arteries, including pudendal arteries, Human Leg Bones, McStrother.

Shema of arteries arising from the iliac and femoral arteries, including pudendal arteries, Human Leg Bones, McStrother.Maintaining a robust nerve supply is second only to the importance of blood supply for eventually restoring sexual function. CTA identifies both the vessels and the nerves, which follow the path of the blood supply. So the surgeons are connecting nerves and blood vessels and hoping the connections will hold, Choi said.

"It's a very delicate procedure," he said of the 15-hour operation on Manning. "You're connecting small vascular structures, and you want to image both the vessel and the nerves so the surgeon can hook them together."

As part of an emerging penile transplant protocol being developed, Choi's colleague Dr. William Liu performs invasive angiography to get a better look at the vasculature. Finally, abdominal MRI expert Dr. Mukesh Harisinghani performs an MRI scan of the region. Dr. Dicken Ko, an associate professor of surgery at MGH, is overseeing Manning's case, which involved more than 50 doctors and nurses.

A week after the procedure, the patient was doing well, without signs of bleeding, infection, or rejection of the organ, according to the hospital. The ability to urinate normally will come in a couple of weeks, followed by sexual function in a couple of months. Drugs to keep Manning's body from rejecting the organ will probably need to be taken for a lifetime, Choi said.

A growing need

Military injuries are a key reason the number of cases needing transplantation are growing, as burns, accidents, cancer, and scarring from injury add to the toll, Choi said. Although each case is different, the team at MGH is creating a protocol aimed at optimizing the success of future transplant procedures.

Right now "it's not so standardized," Choi said, but that's changing. The team is creating a comprehensive imaging protocol to ensure all are prepared. On the interventional side, the surgeons have been training in the lab, learning how to connect the donor organ with the recipient structures in the pelvis.

"This is actually a very bold procedure," he said. "They are connecting two structures with the hope that the connection actually holds. Then the transplant is successful. That's what they're monitoring for right now."

"We are hopeful that these reconstructive techniques will allow us to alleviate the suffering and despair of those who have experienced devastating genitourinary injuries and are often so despondent they consider taking their own lives," said plastic and reconstructive surgeon Dr. Curtis Cetrulo in a statement provided by the hospital.

Thanking the medical team and the family of the donor, Manning said he has received a second chance he never thought possible, according to MGH.

"In sharing this success, it's my hope we can usher in a bright future for this type of transplantation," Manning said.