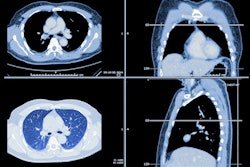

In critically ill patients, the presence of interstitial lung abnormalities detected on CT scans increases a patient's risk of dying in the hospital, concludes a recent study. But the modality can help by diagnosing more patients and identifying those at greater risk.

The association between interstitial lung abnormalities and the risk of in-hospital death had not been previously investigated, but the finding could lead to reduced mortality through better management of patients' existing CT data, said lead investigator Dr. Rachel Putman in an interview with AuntMinnie.com.

"We found a strong association between having those abnormalities and having acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS] -- and that having those changes put people at increased risk of dying while in the hospital," said Putnam, who is a clinical fellow in medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. She presented the research at the 2016 American Thoracic Society (ATS) meeting in May in San Francisco.

Evaluating the risk

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is known to be associated with an increased risk of poor outcomes, but the extent of the added risk is undefined, Putman said. Genetic and physiologic markers of the disease have also been found, and ILD patients are known to have outcomes similar to those with pulmonary fibrosis.

"Our group has been using radiology to sort of define who these patients are in hopes of trying to understand the natural history of the disease, and perhaps do some secondary prevention to identify whether it's the radiology, the genetics, biomarkers, or whatever we can find that will help us progress," she said.

Right now, the range of findings associated with ILD is broad, and one goal moving forward is to identify the factors that make some patients sicker and more likely to die. Already, some radiologic patterns have been found to be associated with higher risk, she added.

Pulmonary fibrosis and mortality risk

The worst form of pulmonary fibrosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), is known to progress, and when it does, it shows the exact same pathology on autopsy as acute respiratory distress syndrome -- that is, diffuse alveolar damage, Putman explained.

"The pathology of IPF is diffuse alveolar damage and the pathology of ARDS is diffuse alveolar damage," she said. "We wondered if the patients who had those earlier fibrotic changes on prior CT scans would be at increased risk of ARDS."

The study retrospectively examined 55 patients with ARDS who had undergone chest CT prior to admission in the intensive care unit (ICU) for reasons unrelated to their admission; they were compared with a control group of individuals without ARDS. Readers blinded to the clinical data evaluated the pre-ARDS chest CT scans for interstitial lung abnormalities. Putman and colleagues used multivariable logistic regression models to evaluate the association between these abnormalities and in-hospital mortality.

"We found a strong association between having those changes and having ARDS, and having those changes put people at increased risk of dying in the hospital," Putman said.

Occurring together

More than one-third (36%) of patients with ARDS had interstitial lung abnormalities, while 40% of ARDS patients were indeterminate for interstitial lung abnormalities. Thirteen patients (24%) had no abnormalities, the study team reported. Among patients without ARDS, 11% had interstitial lung abnormalities, another 49% were indeterminate for interstitial lung abnormalities, and 40% had no such abnormalities.

The researchers confirmed the association between ARDS and interstitial lung abnormalities after adjusting for key covariates including age, smoking history, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II mortality risk score. Interstitial lung abnormalities were also associated with in-hospital mortality.

The results suggest that patients with ARDS may include some with undiagnosed interstitial lung disease, and in some cases, ILD may be a risk factor for ARDS, the team concluded.

There were limitations to the study, however. For example, available data did not permit a mortality analysis based on the death index, so the results were limited to measuring in-hospital deaths, Putman said. Studying a larger cohort and measuring mortality more broadly would improve future studies.

But even from these modest results, it may be possible to improve outcomes by paying more attention to prior imaging in ICU patients, she said.

"I think you can do this reverse investigation more systematically," Putman said. "When we see a patient in the ICU with acute illness, we could systematically go through their prior imaging to look for any abnormalities such as early mild pulmonary fibrosis."