As their experience with subsolid nodules at CT grows, radiologists are learning more about their characteristics and potential risk of malignancy. Overall, the past several years have seen nodule size and growth rise in importance relative to CT density, a less reliable predictor of malignancy.

What are the different lesion types that characterize subsolid nodules? What are we learning about the clinical significance of ground-glass opacities or mixed solid nodules? And how good is the correlation between radiology and pathology? Dr. Brett Elicker from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) examined these questions in a talk earlier this month at the International Society for Computed Tomography (ISCT) meeting in San Francisco.

"Density doesn't always predict whether a lesion is preinvasive or invasive, but we can use other features to refine our ability to detect malignancies," said Elicker, who is an associate professor of clinical radiology and chief of cardiac and pulmonary imaging at UCSF.

Changing approach

In 2011, publication of new nodule criteria by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC), the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) spurred the shift in nomenclature to be more in line with pathology. Radiologists should use the latest terminology to ensure that their descriptions fit with the rest of radiology and pathology, Elicker said.

Within this naming system, tumors are divided into preinvasive lesions without invasion of underlying parenchyma and invasive lesions, where there is a small or larger area of focal parenchymal invasion.

"Obviously that's a really important distinction in terms of patient prognosis and what to expect in terms of mets, etc." Elicker said.

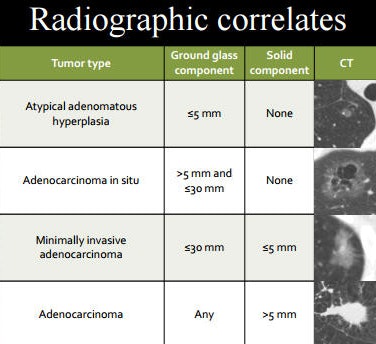

What the radiologist calls invasive carcinoma corresponds to an invasive component larger than 5 cm for the pathologist. Meanwhile, the radiologist's adenocarcinoma in situ corresponds to the pathologist's assessment of lepidic growth only without invasion versus atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, which the pathologist refers to as atypical cells without an invasive component.

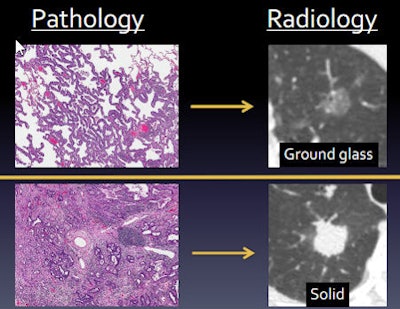

"We assume, or at least we hope, that the pathology and radiology correlate pretty well, so a lot of what we do is based on the concept that lepidic growth ... generally corresponds to ground glass on CT scans," Elicker said.

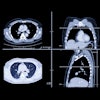

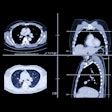

Subsolid nodule pathology (left) versus radiology (right) in CT images of the lung. All images courtesy of Dr. Brett Elicker.

Subsolid nodule pathology (left) versus radiology (right) in CT images of the lung. All images courtesy of Dr. Brett Elicker.The intermediate density of the ground-glass nodule on CT results from thickening of the alveolar wall, whose density is intermixed and averaged with air in the alveolar spaces. Confluent tumor such as an invasive adenocarcinoma, on the other hand, presents a more solid nodule density on CT. These density differences "form the basis of how we determine whether nodules are more preinvasive or invasive or mixed," he said.

But does it work?

How well does CT correlate with pathology? Pretty well most of the time, according to Elicker. When ground-glass nodules get larger or start to develop solid components, the criteria to consider intervention are present.

There is no perfect way to tell, of course, but if the radiology-pathology correlation worked perfectly, a solid component that is 5 mm or smaller would always be a minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, and a larger solid component would be a frank adenocarcinoma. But the correlation can't be relied on, and even pure ground-glass nodules aren't reliably benign, he said.

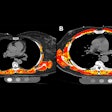

Radiographic correlates for different types of subsolid nodules.

Radiographic correlates for different types of subsolid nodules.For example, lung nodule experts Lee et al from Seoul National University College of Medicine performed a 2013 study examining 272 preinvasive nodules. Nearly one-third of pure ground-glass nodules had invasive components or invasive adenocarcinomas. Twenty-three percent of mixed solid ground-glass nodules were completely noninvasive without invasive components, while 77% were invasive, making density instructive but not absolutely predictive.

"So the radiology is not bad, but it's not perfect, and there are other ways we can improve our ability to further characterize these as invasive or not invasive," Elicker said.

Where might radiology and pathology disagree? Three areas, according to Elicker:

- There could be microscopic areas of invasion too small to be visible at CT.

- Alveolar collapse can show solid areas that make a lesion look invasive when it is only preinvasive.

- There can be measurement discrepancies because pathologists measure things differently than radiologists.

In another study, Lee et al looked at 59 subsolid nodules to find features suggestive of invasive carcinoma: The most predictive features were size larger than 1 to 2 cm, solid components larger than 3 mm, and the presence of spiculations and pleural retractions.

They confirmed that nodules with a solid component 1 cm or smaller are almost always preinvasive, Elicker said.

"When the solid component is larger and if there's any speculation or pleural retraction we would be more worried," he said.

But are these CT-detected nodules clinically significant? Findings from the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) suggest that almost 80% of "these indolent tumors we used to call bronchoalveolar carcinomas" are overdiagnosed and resected unnecessarily, he said. How do we move past this limitation to intervene when it's necessary?

Size and growth over time

Growth can be used as a surrogate for aggressive subsolid lesions, and the bigger lesions are, the more likely they are to grow. In 2016, Lee et al looked at ground-glass and part-solid nodules to assess the correlation between growth rate and malignancy. Fourteen percent of ground-glass nodules smaller than 10 mm grew in five years, versus 71% of ground-glass nodules larger than 10 mm in diameter.

For subsolid nodules in the 2016 study, the numbers were similar: 22% of the smaller nodules grew in five years, versus 79% of subsolid nodules larger than 10 mm, Elicker said. And nodules that grow, particularly over two to three years, are more likely to be invasive. An International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP) study showed that 84% of these growing nodules were invasive adenocarcinomas. They are not necessarily killing people, however, particularly when resected.

A couple of screening studies, one looking at pure ground-glass opacities and one looking at mixed, examined the results of patients whose subsolid lesions were resected after being watched for a couple of years, on average.

In both studies, "no patients had lymphatic or distant metastases, and 100% had cancer-free survival, so we're clearly too sensitive in our detection," he said.

As for conclusions, density doesn't always predict preinvasive versus invasive subsolid nodules, Elicker said. Size works a little better: smaller than 1 cm, you're pretty safe. Some indicators of potential invasiveness include size larger than 1 to 2 cm, solid lesion components larger than 3 mm, and speculation or plural retractions.

In addition, ground-glass nodules that grow or develop solid components are typically invasive, he said. But metastases from subsolid invasive adenocarcinomas are rare.