Administering oral plus intravenous (IV) contrast to children who were in the emergency department undergoing CT exams for suspicion of acute appendicitis increased their wait time without providing any diagnostic benefit, according to a study published in Emergency Radiology.

Dr. Bradford Betz from Helen DeVos Children's Hospital.

Dr. Bradford Betz from Helen DeVos Children's Hospital.

It's still important to administer IV contrast as part of the evaluation of suspected appendicitis in childhood; however, oral contrast can be eliminated without affecting the diagnostic accuracy of CT, senior author Dr. Bradford Betz told AuntMinnie.com.

"Most children do not need CT to evaluate their abdominal pain, but if they do, the scan can be obtained much faster and as accurately without giving oral contrast," he said. "We suspect that more rapid CT diagnosis in the emergency department should shorten turnaround times, reduce costs, and improve the experience of families."

Contrasting opinions

Lacking radiation, ultrasound and MRI have been rising in popularity to confirm suspected cases of appendicitis in children, according to the authors. Yet CT continues to be highly favored for the task because of its diagnostic accuracy, rapid acquisition time, and widespread availability.

There has been a sharp drop in recent years in the use of oral contrast with CT for a plethora of reasons, including cost considerations, increasing radiation dose, patient discomfort, and, most prominently, delayed scanning. At their institution, for example, Betz and colleagues removed oral contrast from their abdominal and pelvic CT protocol for pediatric appendicitis in August 2013.

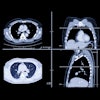

To validate this shift in protocol, the researchers reviewed the abdominal and pelvic CT scans of children who presented to the emergency department with acute, nontraumatic pain near the abdomen. Out of the 558 patients who underwent CT, 288 had only IV contrast and 270 had both IV and oral contrast (Isovue-370 and Isovue-300, Bracco Diagnostics). Physicians administered IV contrast 70 seconds before the CT exam, and they gave half of the oral contrast at two hours before scanning and the other half at one hour before scanning.

After comparing interpretations of the CT scans, the group found no statistically significant difference in the diagnosis of appendicitis when using oral and IV contrast CT versus IV contrast CT alone (p = 0.903).

| CT with oral and IV contrast vs. IV contrast alone to diagnose appendicitis | ||

| Oral + IV contrast CT | IV contrast CT | |

| Sensitivity | 93.8% | 94.6%* |

| Specificity | 98.5% | 98.3%* |

| Average CT turnaround time | 137.4 minutes | 43.8 minutes |

Administering oral contrast to children who also received IV contrast more than tripled the average amount of time they waited, measuring from when the CT exam was ordered to when it was finally performed (p < 0.001). Oral contrast did not reach the cecum in 48% of the patients who took it.

Matching accuracy

The diagnostic accuracies of the two contrast CT protocols were the same even after the data were categorized by physician specialty. Radiologists with subspecialty training in pediatrics identified appendicitis with near-identical specificity (90.9% versus 95.4%) and sensitivity (99.3% versus 98%) as other radiologists.

What's more, perforation of the appendix occurred with nearly the same frequency regardless of contrast protocol in the 125 appendectomy patients. Perforation occurred in 38.8% of patients who took oral contrast and 43.1% of those who did not (p = 0.626). In addition, a periappendiceal abscess was present in 19.4% of children in the oral contrast group and 25.9% of those who didn't get oral contrast (p = 0.388).

"Despite the inherent scan delay associated with giving oral contrast, we did not find that these children were more likely to have an appendiceal perforation," Betz said. "This observation seems to reinforce the belief that brief delays in diagnosis -- such as waiting for oral contrast -- may be less significant than once thought."

One of the limitations of the study was the increasing use of ultrasound before CT scanning, the authors noted. Having prior knowledge of ultrasound results could have influenced the final diagnosis of appendicitis, although an analysis of the data suggests it likely had little to no effect on the whole: The diagnostic accuracy of the radiologists fell within a tight range of 96.7% to 98% when evaluating patients either with or without knowledge of prior ultrasound results for both contrast protocols (p = 1.0).

This study in no way rules out the use of MRI and ultrasound for diagnosing pediatric appendicitis, but it does appear to reinforce the value of CT for the task -- particularly for its high diagnostic accuracy.

"We prefer IV contrast for CT because it facilitates identifying the appendix with the low-dose techniques we use; plus it helps us recognize appendicitis mimics such as pyelonephritis," Betz said. "Based on our experience with CT, we would recommend CT even if it was necessary to perform it without IV contrast."