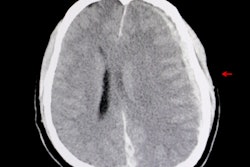

A blood test that detects biomarkers for brain injury could help rule out patients suspected of having traumatic intracranial injuries, thus avoiding the need for CT scans, according to a large multicenter observational trial published online July 24 by Lancet Neurology.

Researchers from the U.S and Europe found the blood test correctly identified 99.6% of patients who did not have a traumatic intracranial injury on head CT scans in a study of more than 1,900 adults -- mostly with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) -- who presented to emergency departments in the U.S. and Europe.

Routine use of the new biomarker test in emergency departments could reduce head CT scans by a third in patients with acute head injury thought to be in need of CT scanning, avoiding unnecessary CT-associated costs and radiation exposure, with a very low false-negative rate, according to Dr. Jeffrey Bazarian at the University of Rochester School of Medicine in Rochester, NY, who co-led the research.

"Our results suggest that patients with mild TBI (initial GCS [Glasgow Coma Scale] of 14 or 15) who have no other indication for a CT (such as a focal neurologic deficit), and who have a negative test, can safely avoid a CT scan," he noted in a press statement. "Those patients with a positive test have a 10% chance of an intracranial lesion, and most clinicians would get a CT scan of their head to determine if an intracranial injury exists and define it further."

Making a decision

To scan or not to scan, that is the question.

To scan or not to scan, that is the question.Current practice for mild TBI involves a series of checklists of symptoms and signs -- known as clinical decision rules -- that a treating physician will look for to decide whether a CT scan is necessary, the researchers explained. An important clinical guide for determining the need for a CT scan is the patient's initial level of alertness, measured using the Glasgow Coma Scale score, with some guidelines recommending a head CT scan for anyone with a less than perfect GCS score of 15.

But sending too many ER patients on for CT scans if they turn out to be negative for brain injury could expose some individuals to unnecessary radiation, while also using up hospital resources. Could these patients be triaged in another way?

Previous research has demonstrated the potential of blood-based brain biomarker tests for assessing TBI, but it wasn't until February 2018 that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a test for use outside the research setting (Banyan BTI, Banyan Biomarkers). The researchers, therefore, decided to investigate the efficacy of the Banyan BTI test, which tests for the presence of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1), two proteins that rapidly appear in the blood shortly after a TBI occurs.

Key findings

The researchers conducted a prospective study of 1,959 adults (age 18 or older) attending emergency departments between December 2012 and March 2014 with suspected TBI at 22 sites in the U.S. and Europe. Participants had a GCS score ranging from 9 to 15, and the majority (98%) had mild TBI, with a score of 14 to 15 (GCS scores range from 3 indicating deep coma to 15 representing full consciousness). All participants received a head CT scan as part of standard emergency care and had blood samples taken within 12 hours of injury.

The results showed that 125 (6%) of participants had intracranial injuries detected on CT and eight (< 1%) had injuries that were neurosurgically manageable. In all, 1,288 (66%) of patients had a positive GFAP and UCH-L1 test result, and 671 (34%) had a negative result.

The new biomarker test was positive in 97.6% of patients with a traumatic injury on head CT scan (sensitivity), while the probability that a patient with a negative test result was truly injury-free was 99.6% (negative predictive value), the authors reported.

Given there were 10 times as many positive GFAP and UCH-L1 tests as positive CT scans among patients with TBI, they speculate these two proteins may be detecting more subtle degrees of injury not visible on CT scans.

"The majority of patients presenting with mild traumatic brain injuries like concussion do not have visible traumatic intracranial injuries on CT scans," pointed out co-lead author Dr. Peter Biberthaler from the Technical University of Munich in Germany. "Given the GFAP and UCH-L1 biomarker test's inherent simplicity, requiring only a blood draw, and its reliability at predicting the absence of intracranial injuries, we are hopeful of its future role in ruling out the need for CT scans in these patients."

Serious doubts raised

Reservations have been expressed about the clinical value of the blood test, however.

Writing in an accompanying comment, Dr. Andrew Maas, PhD, from Antwerp University Hospital and University of Antwerp in Belgium and Hester Lingsma, PhD, from Erasmus University Medical Center in the Netherlands noted that several scientific and clinically relevant questions remain unanswered.

"The only clinically relevant question for any new diagnostic test in mild TBI is 'Does the test add value (e.g., better outcomes or reduced costs) to currently used biomarkers and decision rules?' " they wrote. "Inexplicably, this evaluation was not done."

They suspect that the added value of the test in clinical practice might well be small or even absent, and they strongly encourage the authors to prove them wrong.

In addition, one neuroradiologist who wished to remain anonymous told AuntMinnie.com that it is important to bear in mind a CT scan is associated with very limited radiation dose (1 mSv versus 2 mSv for background radiation annually), as well as relatively small costs and time effort, and this will limit the actual benefit of the blood test.

Furthermore, the expert pointed out that many questions have to be addressed before the test benefits decision-making in the emergency ambulance, including the following:

- How fast are the results of the blood test available?

- What does the blood test cost compared with CT, and how much money can actually be saved?

- What further measures and tests will be needed, and how many patients will require intervention?

- How many patients receive CT scans of other body parts or whole-body trauma CT anyway?

- What is the influence of other neurological comorbidities, such as multiple sclerosis?

"Taken together, I am skeptical if there is really value in clinical practice," the source concluded.

Study limitations

The authors of the Lancet Neurology article conceded there are several limitations to the study, including that it did not evaluate the blood test's predictive ability for clinical outcomes such as prolonged postconcussive symptoms, cognitive impairment, and decreased functional status. They also noted it did not attempt to assess the test's diagnostic accuracy compared with currently used biomarkers and clinical decision rules for triaging patients for CT scanning.

Finally, the sensitivity analysis comparing the diagnostic performance of the biomarker test for each of the proteins separately suggested that GFAP alone might perform as well as the two proteins combined, and it requires further validation.

Study disclosures

The study was funded by Banyan Biomarkers and U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command.