What can today's radiology professionals learn from CT scans of the ancient past? Plenty, according to Swedish researchers, who used a technique called phase-contrast CT to reveal micron-sized details in a mummified hand and published their findings online September 25 in Radiology.

Phase-contrast CT provided microscopic detail of soft-tissue anatomy in the mummified hand of an Egyptian boy who probably lived 2,400 years ago. The researchers believe the resolution of phase-contrast CT surpasses that of conventional CT by a factor of 100 -- and could someday be useful in the clinical realm.

The group, led by lead author and doctoral candidate Jenny Romell from KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, acquired propagation-based phase-contrast CT scans of an ancient Egyptian mummy. They found that the high spatial resolution of this technique allowed them to discern tiny soft-tissue structures -- such as individual layers of skin, fat cells, and blood vessels -- at sub-0.01-mm resolution.

Mummified hand of an Egyptian man from 400 B.C. Image courtesy of Jenny Romell from KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Mummified hand of an Egyptian man from 400 B.C. Image courtesy of Jenny Romell from KTH Royal Institute of Technology."The biggest advantage of phase-contrast CT is that we can image the soft tissue in situ, at high resolution (down to the cellular level) without damaging the sample, which is not possible with other methods," Romell told AuntMinnie.com. "We see phase-contrast CT as a natural complement to the existing methods for the investigation of mummies and other ancient remains."

Give CT a hand

Clinicians and archaeologists have long studied mummified human anatomy through histology -- an invasive method that relies on the extraction of tissue samples, the authors noted. More recently, developments in imaging technology have led to the application of x-ray, CT, and micro-CT in the field as nondestructive options.

But however useful these imaging modalities are for visualizing hard tissues such as bones, they do not provide sufficient contrast to illustrate soft-tissue structures in high detail.

Conventional x-ray and CT are fundamentally limited in imaging soft tissue because they rely solely on the absorption of x-rays to create different degrees of contrast in an image. An alternative to this technique is phase-contrast CT, which measures the absorption of x-rays and also the phase shift of x-rays as they pass through tissue.

This form of propagation-based imaging enhances the contrast of soft tissue in CT scans and, thus, facilitates better differentiation between types of tissues. MRI is also capable of capturing soft tissue but is restricted to resolutions of approximately 1 mm, whereas phase-contrast CT hits resolutions of sub-0.01 mm (6 µm to 9 µm) -- ideal for identifying cellular-sized features.

Evaluating the technique in a laboratory setting, Romell and colleagues performed phase-contrast CT scans on an Egyptian mummy dated to around 400 B.C. They first acquired nine scans of distinct regions of the mummy's hand and then combined these scans into a single dataset using image reconstruction software (Octopus Reconstruction, XRE).

To get an even more detailed look, the group acquired a phase-contrast CT scan of just the tip of the mummy's middle finger. The reduced surface area enabled them to maximize phase contrast by using smaller equipment that provided greater magnification, as well as by increasing the exposure time per scan.

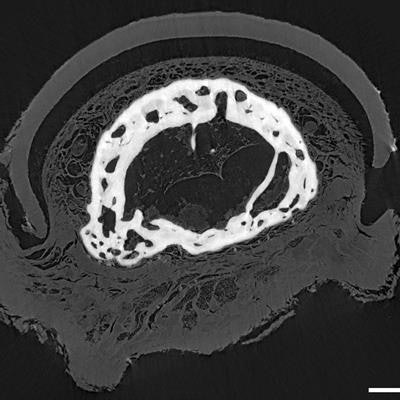

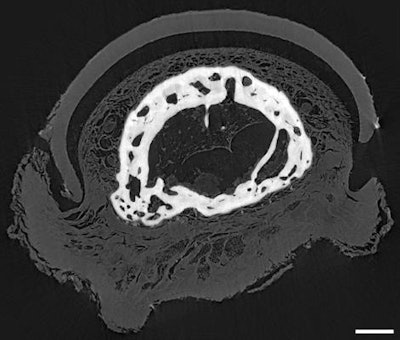

Phase-contrast CT scan of the mummy's middle finger displays vessels, fat tissue, and distinct layers of the skin. The image resolution of this axial section is between 6 µm and 9 µm. The scale bar represents 1 mm. Image courtesy of Jenny Romell.

Phase-contrast CT scan of the mummy's middle finger displays vessels, fat tissue, and distinct layers of the skin. The image resolution of this axial section is between 6 µm and 9 µm. The scale bar represents 1 mm. Image courtesy of Jenny Romell.A closer look

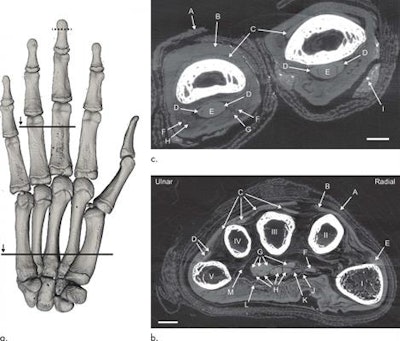

On the volume-rendered images of the entire mummy hand, the researchers were able to visualize the hand bones with comparable resolution to that of micro-CT. They estimated that the mummy was a boy between 13 and 17 years old at the time of his death based on his bone development. Phase-contrast CT scans of the hand also helped them to identify linen, skin, tendons, and ligaments, as well as larger nerves and arteries such as the ulnar nerve and artery.

Volume-rendered reconstruction of the phase-contrast CT scan of a mummified hand (a). Axial view of the hand (b). Axial section of the third and fourth fingers (c). Image courtesy of RSNA.

Volume-rendered reconstruction of the phase-contrast CT scan of a mummified hand (a). Axial view of the hand (b). Axial section of the third and fourth fingers (c). Image courtesy of RSNA.The phase-contrast CT scans of the isolated fingertip revealed additional features not observed on the scans of the hand, including microvessels and tiny nerves in the nail bed, fat cells (i.e., adipocytes), and traces of bone marrow. Romell and colleagues found that this anatomy had excellent correspondence with the detailed anatomy presented in contemporary medical textbooks.

Phase-contrast CT produces a high spatial-resolution volume-rendered image that allows for a simplified and improved way to differentiate between pathologic and healthy tissue, the authors noted. This reduces the risk of missing soft-tissue pathology, compared with conventional absorption-contrast CT.

What's more, the detailed 3D volume map of reconstructed phase-contrast CT scans lets clinicians examine the anatomy from multiple perspectives, as opposed to the 2D viewing capabilities of extractive histology.

The researchers acknowledged several limitations to the technique, including a relatively small field-of-view and long exposure times, leading to increased radiation dose. The total exposure time for the fingertip scans was 8.3 hours per scan, with an average radiation dose of a few grays.

Technical improvements are needed when it comes to x-ray sources and detectors before clinicians can start safely using phase-contrast CT to visualize soft tissue in living humans, Romell said.

Doctors in the driver's seat

What role might radiologists and other physicians play in the development of this technology?

"In the field of paleopathology, I would say that medical doctors play the biggest role, as they are the ones that can truly appreciate the impact of new technology and are constantly driving the search for novel methods of imaging," Romell said.

The researchers suggested that it may soon be possible to apply phase-contrast imaging to nano-CT for detecting even smaller soft-tissue structures with continued advancements in the field.

"The medical doctors and archaeologists in the communities of mummy studies, paleopathology, and evolutionary medicine will ultimately be the ones to decide the role of phase-contrast CT in their fields," she said. "We hope that this new method will help them in their research and lead to new discoveries."