Dear AuntMinnie Member,

The big news this week was a proposal floated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that could lead to looser rules on how exposure to ionizing radiation is regulated by the federal government.

The proposal is being developed under the guise of promoting transparency in the use of science to develop federal regulations. But it basically represents a shift away from the dominant view of radiation that has informed federal regulation for decades: the linear no-threshold theory, which holds that no level of radiation is considered safe, and even small doses could contribute to the development of cancer.

In raising the new proposal, the EPA seems to be moving in favor of the radiation hormesis model, which asserts that the linear no-threshold theory is unproven and, at very small doses, radiation could even have a beneficial effect on the human body.

The EPA transparency proposal was discussed at a Senate hearing held this week in Washington, DC, at which several radiation hormesis advocates testified. For our article on the proposal, click here.

First, it should be noted that the EPA doesn't regulate healthcare providers, and there has been no corresponding move by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Also, proponents of radiation hormesis raise valid points about whether the long-term studies conducted on radiation risk -- which have involved survivors of the atomic bomb attacks -- are really applicable to very low-level exposures, such as those encountered in medical imaging.

But now is neither the time nor the place to relax rules on medical radiation exposure. Just 10 years ago, radiology witnessed a series of cases in which patients received massive overdoses of radiation from CT scans. Those tragic incidents highlighted a stunning fact: that radiology professionals at the time had little to no knowledge of exactly how much radiation their patients were receiving.

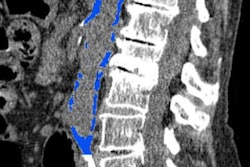

Things have changed since then -- for the better. CT vendors have driven radiation dose down to levels below 1 mSv for some scans, a remarkable achievement. Imaging providers have a much better handle on dose exposure for patients, thanks largely to software that can track dose not only for one-time exposures but also for long-term monitoring over a patient's history -- and can alert providers to excessive exposure. And organizations have raised awareness of the risks of unnecessary scans and the variability in protocols that can lead to different doses for the same procedures. These are all welcome developments that never would have happened were it not for concern about the health effects of low levels of radiation.

It took 10 years to rebuild public trust in radiology professionals as responsible stewards of radiation dose following the accidents of 2008 and 2009. There is no need to undermine that trust by relaxing rules that are reasonably based on the best science we currently have on the risks of radiation exposure.