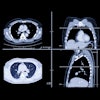

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has released an updated, final recommendation for CT lung cancer screening that lowers the starting age from 55 to 50 and adjusts smoking history from 30 pack years to 20 pack years. The final recommendation was published March 9 in JAMA.

The guidance updates the task force's 2013 recommendation. It now states that adults between the ages of 50 and 80 who have a 20 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years should undergo annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose CT. As in 2013, the task force has given the guidance a "B" grade, which translates to the following:

"The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that annual screening for lung cancer with low dose CT has moderate net benefit in persons at high risk of lung cancer based on age, total cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke, and years since quitting smoking," it wrote. "The moderate net benefit of screening depends on limiting screening to persons at high risk, the accuracy of image interpretation being similar to or better than that found in clinical trials, and the resolution of most false-positive results with serial imaging rather than invasive procedures."

For the update, the USPSTF conducted a review of 220 studies that investigated screening for lung cancer with low-dose CT, including data from the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) and the Netherlands-Leuvens Longkanker Screenings Onderzoek (NELSON) trials. The group also commissioned a modeling study from the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) Lung Cancer Working Group to address questions about when to start screening, the best screening interval, and the benefits and harms of different screening strategies.

Addressing healthcare inequities

The USPSTF's adjusted guideline should help catch lung cancer earlier, when it is more treatable, and also mitigate healthcare inequities, particularly differences among racial/ethnic group and between men and women, according to the USPSTF.

"A strategy of annually screening persons age 50 to 80 years who have at least a 20 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years ... would increase the relative percentage of persons eligible for screening by 87% overall -- 78% in non-Hispanic White adults, 107% in non-Hispanic Black adults, and 112% in Hispanic adults compared with 2013 USPSTF criteria," it wrote. "Similarly, [this strategy] would increase the relative percentage of persons eligible for screening by 80% in men and by 96% in women."

The new guidance was met with immediate response, with multiple articles published on March 9 in JAMA Oncology and JAMA Surgery.

The updated recommendation will boost the number of people eligible for screening, but implementation challenges remain, wrote a team led by Dr. Mayuko Ito Fukunaga of the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester in an accompanying editorial in JAMA Oncology.

These challenges include how shared decision-making should be accomplished, whether low-dose CT is actually available at a given facility, and assessing the risks and benefits of screening -- which may include radiation-induced cancers, patient distress regarding screen-detected findings, physical complications related to invasive procedures, and overdiagnosis.

"Lung cancer screening is not just an imaging study," the group wrote. "It is a complex process ... policy efforts are critical to ensuring that the benefits of lung cancer screening outweigh the harms at the population level, [but] may exacerbate disparities in lung cancer outcomes if only highly resourced settings have the ability to implement comprehensive, high-quality lung cancer screening programs, making screening inaccessible to individuals with higher lung cancer risk, such as socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals and rural populations."

In an editorial in JAMA Surgery, a group led by Dr. Yolonda Colson, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, deemed the new guidelines to be "better but not enough," warning that increasing the eligible population doesn't necessarily mean that more people will take advantage of screening unless concentrated effort toward this outcome is made.

"Success requires access and [patient] willingness to undergo screening and follow-up within a coordinated multidisciplinary lung cancer screening program," Colson and colleagues wrote. "The additional support of patient navigators, smoking cessation counselors, hospital information systems, marketing and finance teams, and community partners are critical to overcoming the barriers that have prevented success to date."