Per-patient grouping for liver tumor status based on LI-RADS and treatment response shows low negative predictive value (NPV) in detecting residual or untreated tumors, according to research published December 19 in Radiology.

A team led by Omar Hassan, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco studied hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients who underwent local-regional therapy followed by liver transplant. The team found that per-patient stratification of tumor status at either pretransplant CT or MRI based on the LI-RADS version 2018 treatment response algorithm showed low NPV in this area.

“The relatively low negative predictive value may contribute to clinical under-staging, delaying care for patients who need to undergo transplants and potentially allocating transplants to patients out of the Milan criteria,” the Hassan team wrote.

The LI-RADS treatment response algorithm grades the diagnosis of HCC and recurrence after local-regional therapy. The system has high specificity, but low sensitivity. However, the researchers noted that the emphasis on specificity can lead to disease under-staging. This could result in poorer post-transplant outcomes.

Hassan and colleagues studied the NPVs of pre-transplant CT and MRI assessment for viable HCC on a per-patient basis. They used the LI-RADS treatment response algorithm and used explant pathology as the reference standard.

The team included patient records from 206 HCC patients who underwent a liver transplant from 2011 to 2017. Two readers blinded to the original report reviewed immediate pretransplant imaging within 90 days and characterized observations according to the LI-RADS algorithm.

Using this, tumors were categorized into the following: viable (LI-RADS 4, 5, or treatment response), equivocal (LI-RADS 3 or treatment response), and no viable disease (only LI-RADS treatment response). Meanwhile, the patients were designated as within or outside the Milan criteria for liver transplantation. The team compared these per-patient designations with the presence of viable disease at explant pathology.

The researchers found that per-patient assessment of pretransplant imaging had an NPV of 32% and 26% for both readers in predicting viable disease.

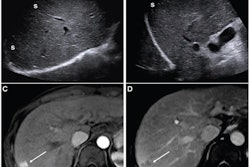

Images in a 55-year-old patient show hepatitis C-related cirrhosis and a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (dashed arrow), with an undiagnosed tumor (dashed circle) at pretransplant imaging by both readers. Left: Noncontrast-enhanced axial CT image with a treated observation (dashed circles on the left, middle, and right images) and dense lipiodol staining (arrows) in the anterior right liver. Middle: Late arterial phase CT image with no appreciable enhancement. Right: Delayed phase image with no appreciable washout. The lesion was deemed at explant pathology to have 20% necrosis. Image courtesy of RSNA.

Images in a 55-year-old patient show hepatitis C-related cirrhosis and a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (dashed arrow), with an undiagnosed tumor (dashed circle) at pretransplant imaging by both readers. Left: Noncontrast-enhanced axial CT image with a treated observation (dashed circles on the left, middle, and right images) and dense lipiodol staining (arrows) in the anterior right liver. Middle: Late arterial phase CT image with no appreciable enhancement. Right: Delayed phase image with no appreciable washout. The lesion was deemed at explant pathology to have 20% necrosis. Image courtesy of RSNA.

They also reported that 75% (reader 1) and 77% (reader 2) of patients found to have had equivocal status had residual tumors at explant pathology. Finally, the team found that the weighted interreader reliability was marked (κ = 0.62).

“LR-3 and LR-treatment response equivocal tumors are typically not treated aggressively; thus, patients with equivocal imaging may not undergo local-regional therapy or have a higher wait list priority, delaying both bridging and definitive treatment times,” the study authors wrote.

The authors also called for more research to better understand factors leading to HCC under-detection along with the extent of residual disease that leads to clinically significant outcomes.

In an accompanying editorial, Shlomit Tamir, MD, and Noam Tau, MD, from Tel Aviv University wrote that per-patient evaluation could be a preferred approach given the scarcity of available organs for transplantation. They added that the limitations of LI-RADS in this setting does not necessarily imply that imaging or the classification system specifically are not sufficient for HCC evaluation in liver transplant candidates.

“In fact, imaging may be more appropriate than pathology as a prognostic indicator for recurrence or survival, depending on the clinical outcomes of the patients in whom discrepancy was noted,” the editorial authors wrote.

They concurred that future studies are needed to assess whole-liver explant results, combining per-lesion and per-patient analysis.

The full study can be found here.