In 2003, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) opened its first hybrid surgical operating room (OR) for endovascular procedures. By combining the nonsurgical techniques used in imaging with the surgical techniques needed for vascular procedures, the era of hybrid minimally invasive vascular surgery at MGH began.

Because it was a retrofit, this prototype installation had clear limitations, including a fixed ceiling-mounted C-arm and a fixed surgical table. However, working within these constraints forced us to confront several important design and workflow challenges; as a result, we had a solid base of experience over several years as we entered the process of designing four hybrid OR suites.

The new suites opened for use in August 2011. These rooms combine floor-mounted and ceiling-mounted imaging equipment with state-of-the-art imaging displays, full PACS and IT connectivity, advanced rotational imaging and 3D postprocessing capabilities, advanced radiofrequency-enabled supply management systems, and a number of other custom-designed solutions.

Designing the hybrid OR suite

Our overarching design philosophy was to start by establishing the likely procedure mix for each room, i.e., "functional programming." This, in turn, guided the selection of people to serve on the design team and subsequently was key in determining the appropriate equipment and other support systems to go into each room. We knew that pulling together the right team would be important not just during the design phase but to gain support for initiating clinical service in a multidisciplinary environment.

We also hoped to contribute to the growth of a "just culture" for employees,1 focused on group responsibility for patient safety and supported by cross-disciplinary team training and education. Regarding the infrastructure and space capacity requirements, a complete inventory of equipment and supplies was put together and was important, but we found we needed to look beyond vendor specifications to create custom solutions to best serve the competing needs of the room. In our case, two examples of such custom solutions emerged: a "breakable" and exchangeable OR table and "quick connect" cabling.

The design team

There is considerable research that suggests diversity and conflict are essential ingredients to innovation.2 We learned from our first foray into building hybrid suites that we needed to have the right experts from all relevant disciplines to maximize the opportunities for generating ideas, design options, and alternative solutions. We also needed executive leadership support to make sure that those with decision-making power in the hospital were at the table.3

To this end, we formed an executive project team (EPT) early in the process to make sure we had team members who understood how the suites were intended to function and who also had the decision-making authority to move the project from the conceptual phase forward. The team included the following members: the executive medical director of the OR, the associate chief nurse of perioperative services, the OR nursing director, the director of interventional radiology (IR), the clinical nurse manager, the project manager of perioperative services, the clinical nurse specialist, vascular and anesthesia physicians, and, finally, the architect team. The physicians on the team represented all of the services that would be providing care in our hybrid suites. We also held weekly construction meetings and biweekly field reviews with project managers, the construction foreman, and architects.

In addition to the executive project team, we formed a second-tier end-user team to include clinical directors, nurses, technologists, and physicians (consisting of vascular surgeons and neuro and vascular interventional radiologists), who were to work in the rooms, as well as architects and project managers. While the executive project team provided executive support and set the guiding principles, the end-user team ensured that design details met the requirements of real workflow logistics.

Functional programming as a driver for operational design

We understood that making the right connections between functional programming of the suite and the operational design -- more specifically, to have a comprehensive understanding of the services and types of procedures that would be performed in the suite -- would be critical to success.

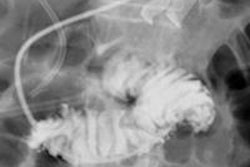

In our case, the rooms needed to accommodate both interventional radiology cases and neuro and vascular surgical cases, whether open or closed, requiring anesthesia support. The increased demand for anesthesia services in interventional procedures makes it important to have anesthesiologists in close proximity to the IR suites for support and consultation. Therefore, a secondary goal in the design was to maximize the efficiency and flexibility of anesthesia delivery by providing space for anesthesiology in the same area of the operating room as the IR suites. By colocating anesthesia providers, we helped satisfy the overarching goal of ensuring patient safety, recovery, and well-being within an operationally efficient unit.

Biplane vs. single-plane imaging devices

One of the fundamental issues in the design of a hybrid OR suite is the choice for each room between biplane and single-plane imaging devices. If the projected case mix favors neuroendovascular procedures, biplane devices are desirable. However, the trade-off is a less effective setup for open procedures owing to the nature of the imaging table.

Currently, pedestal tables are not compatible with biplane devices, thus requiring surgeons to perform open techniques on an imaging table when biplanes are installed in hybrid operating rooms. On the other hand, if it is projected that only a limited number of neurological procedures will be performed in the suite (if any), a single-plane imaging device is a more appropriate selection from cost and operational efficiency standpoints.

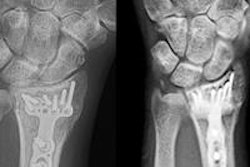

Thanks in part to the development of faster and smaller microprocessors, the capabilities of both single and biplane devices have evolved rapidly in recent years. They now offer a host of axial imaging acquisition and postprocessing options with 3D imaging capability.4 Further, incorporation of robotics helps increase the flexibility in positioning these advanced imaging devices.

As more use of intraoperative axial imaging has become the standard of care in vascular practices, the consideration for more flexible C-arm positioning has become a critical factor in a hybrid suite. This is due to the nature of complex vascular hybrid procedures such as endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) and thoracic endovascular aortic/aneurysm repair (TEVAR), which may require various angles for image visualization and rotational angiography during the case.

Furthermore, having the ability to move the C-arm out of the surgical field for open cases and for a certain time during a hybrid procedure when no imaging is required enhances the intraoperative workflow and arguably patient safety. A C-arm mounted on a robotic arm with numerous pivoting joints allows for great flexibility in imaging the patient, superior axial imaging, and the ability to move the C-arm out of the way when not in use.

Given these considerations and our projected case mix, we decided that we should have two rooms each for biplane and single-plane devices: the biplane units primarily for the neuro work and the single-plane unit for abdominal, peripheral, EVAR, and TEVAR procedures.