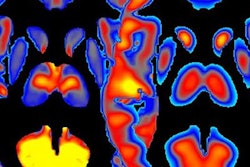

SAN FRANCISCO - Keggers and beer bongs may be a ubiquitous part of a young man's college experience, but even such short-term heavy drinking can cause significant neurological changes, according to a presentation last week at the American Psychological Association (APA) meeting. Researchers from Wittenberg University in Springfield, OH, used FDG-PET imaging to detect changes in brain function among young male alcohol abusers.

"This (study) is an early warning signal that these changes are taking place at an early age," said Josephine Wilson, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at the university.

Wilson and colleagues recruited 20 young men, ages 21-25, for the study. The subjects did not have a history of recreational drug use, were not on psychotropic medication, and did not have a history of traumatic brain injury. Ten men were classified as drinkers; a second group of nondrinkers were classified as abstainers for the purposes of the study, Wilson said.

The subjects all refrained from drinking for 24 hours prior to the two-day test period. One the first day of the study, the students underwent urine and blood testing, physical exams, and a battery of neuropsychological tests, including the California Verbal Learning Test and a fine motor test. FDG-PET studies were done on day one while the subjects participated in the Letter-Number Sequencing Test for 20 minutes. On the second day, urine and blood tests were repeated along with another PET scan and an MRI. The images were co-registered.

"No statistically significant differences between drinkers and abstainers were found for any of the neuropsychological measures obtained," Wilson reported. But when the brain images were reviewed and compared, Wilson's group found statistically different functional use in the right cerebral hemisphere in the primary visual cortex (p < 0.001), the fusiform gyrus of the temporal lobe (p < 0.01), and the left cerebral hemisphere in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (p < 0.01). Additional changes were seen during the Letter-Number Sequencing Test, Wilson said.

The areas that differed between the brains of the drinkers and nondrinkers appeared to reflect similar changes reported by other researchers in older drinkers, she said.

"PET appears to be a highly sensitive technique for detecting early functional changes in the brain due to alcohol abuse," she said.

By Edward Susman

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

August 23, 2007

Related Reading

Brain can repair alcohol's damage, December 19, 2006

PET helps uncover dopamine's influence on alcoholism, October 5, 2006

Smoking stalls neurocognitive recovery in former alcoholics, April 21, 2006

Teen binge drinking can do long-term brain damage, February 15, 2005

Heavy social drinkers show brain damage, study finds, May 15, 2004

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com