PET/MRI showed in a recent study that a loss of cognitive function in older people due to head injuries that knocked them unconscious earlier in life was unrelated to pathology associated with Alzheimer's disease. The findings were published online March 11 in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology.

Previous studies have found links between head injury earlier in life and the development of Alzheimer's disease later. Some studies have also found evidence that head injury is associated with Alzheimer's disease-related pathology markers, according to Dr. Nick Fox, a clinical neurologist and director of the Dementia Research Centre of University College London.

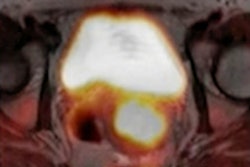

The current study was unable to find a strong association between a head injury that resulted in a loss of consciousness and a range of Alzheimer's biomarkers. But the researchers found that smaller brain volume and adverse microstructural integrity in normal-appearing white matter were more responsible for the lower cognitive function they observed than the Alzheimer's biomarkers as observed on PET/MRI images.

Pathologic changes in Alzheimer's disease are thought to develop at least 10 years prior to the onset of symptoms. Since acute disruptions to biochemical and cytoskeletal functions are thought to happen in all head injuries, researchers in this study used PET/MRI to see if they could determine whether the processes are related.

PET imaging with florbetapir and MRI were performed using a PET/MRI scanner (Biograph mMR, Siemens Healthcare) on 502 people between 69 and 71 years old from the 1946 British Birth Cohort. Participants underwent cognitive testing. All were dementia-free.

The researchers measured levels of beta amyloid on PET, brain, hippocampal and white matter hyperintensity volumes, normal-appearing white matter microstructure, Alzheimer's disease-related cortical thickness, and serum neurofilament light chain (NFL) levels.

The researchers found no evidence that a head injury with loss of consciousness was associated with beta-amyloid load, hippocampal volume, volume of white matter hyperintensities, Alzheimer's-related cortical thickness, or serum NFL levels. The finds were statistically significant.

Imaging was compared among groups who had reported head injuries either 15 years prior to the exam, at any time up to age 71, or not at all. Only participants who reported a loss-of-consciousness head injury 15 years prior (16%, n = 80) performed worse on a cognitive single-sheet paper-and-pencil test that required them to match symbols to numbers according to a key located on the top of the page. These individuals had lower psychomotor speed and executive function.

Some of the later-life injuries may have occurred closer to when the PET/MRI occurred and may have been due to aging processes linked to susceptibility to falls, comorbidities, and related medication, or as a consequence of prodromal cognitive impairment, the authors wrote. Thus, the measure of head injury across the life course may have potential cases of reverse causation, the authors suggested.

Another caveat was that the single imaging time point limited inferences concerning the temporal order and progressive nature of neuropathology.

Continued follow-up will provide greater insight into whether the negative effects of head injury on pathological markers and cognitive function are static or dynamic, the authors noted.