With the help of PET scans, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine are gathering information on why the drug rifampin is not very effective in treating tuberculosis meningitis (TBM) of the brain. They reported their results in a study published online December 5 in Science Translational Medicine.

"Really precise information has never been easy to come by for how much rifampin gets to any given patient where it's needed," said study co-author Dr. Sanjay Jain, a professor of pediatrics, radiology, and international health at Johns Hopkins. "We've been able to use technology to find that long-needed information about this very troubling disease."

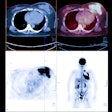

In the study, the researchers engineered a version of rifampin that has a positron radiotracer attached to the drug to follow its movement throughout the body of a rabbit via PET. Rabbits were chosen for the study because their TBM symptoms are similar to those of humans. Levels of the tagged rifampin were tracked in the rabbits' brains over six weeks.

PET scans revealed that after two weeks of treatment, the penetration of rifampin into TBM brain lesions significantly decreased, from 32% to only 11% of the levels of the drug found in the blood. Most importantly, the decrease was not reflected in samples of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) taken from the rabbits. The finding is particularly noteworthy because CSF is currently the standard way to determine drug levels in humans.

The researchers also gave the tagged version of the drug to 10 adult tuberculosis patients who were already receiving rifampin therapy. Similar to the results in rabbits, PET showed that the drug's penetration into brain lesions was less than 5%.

The findings could advance knowledge of why current drug treatments for TBM may not be effective, according to the researchers. The PET approach also offers a potential way to optimize treatment for TBM and ensure that enough rifampin is reaching infected lesions.