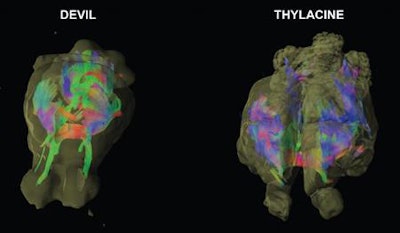

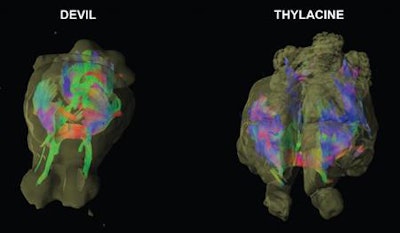

Scientists have used MRI and diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI) to reconstruct the brain architecture and neural networks of the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, an extinct carnivorous marsupial native to Tasmania, according to research published online January 18 in PLOS One.

When the tiger was compared with its closest living relative, the Tasmanian devil, the tiger had more brain power for planning and decision-making, concluded a team led by neuroscientist Dr. Gregory Berns, PhD, from Emory University. The results also support theories of brain evolution that suggest brains become more modular, dividing into sections that handle discrete functions, as they grow larger.

The Tasmanian tiger appeared about 4 million years ago in Australia, according to the authors. By the 20th century it had died out on the mainland, although it could still be found in Tasmania. The last known Tasmanian tiger died in 1936, in Tasmania's Hobart Zoo.

Image shows the neural pathways of the Tasmanian devil (left) and the thylacine, better known as the Tasmanian tiger. Image courtesy of Emory University.

Image shows the neural pathways of the Tasmanian devil (left) and the thylacine, better known as the Tasmanian tiger. Image courtesy of Emory University.

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)