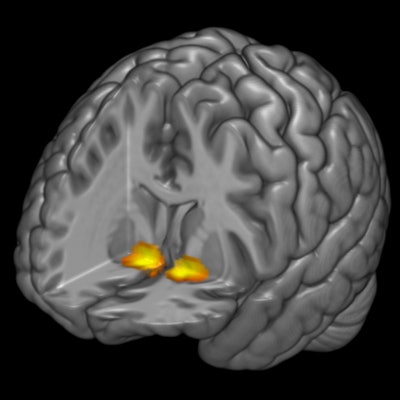

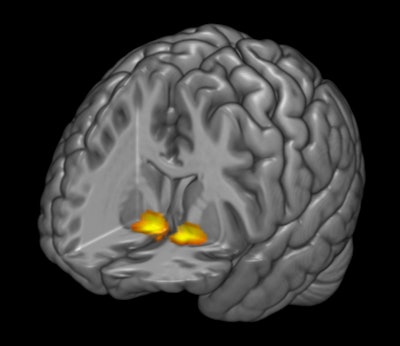

Functional MRI (fMRI) has pinpointed increased activity in a region of the brain associated with reward processing that could help protect against depression due to poor sleep or insomnia, according to a study published online September 18 in the Journal of Neuroscience.

Researchers from Duke University found that subjects with greater reward-related activity in the ventral striatum were less likely to develop symptoms of depression when battling insomnia or difficulty sleeping. With the location of this trigger, caregivers potentially could develop more direct therapies for the condition.

"Our study is the first to show that reward-related ventral striatum activity can moderate the effects of poor sleep on depressive symptoms," said lead author Reut Avinun, PhD, a postdoctoral associate in Duke's neurogenetics lab. "If replicated, it has the potential to help identify individuals who may benefit more from treatment that targets the reward system, whether by direct stimulation of the ventral striatum or by cognitive behavioral therapy."

Sleep and depression

Reut Avinun, PhD, from Duke University.

Reut Avinun, PhD, from Duke University.Poor sleep is one of the more common causes of depression, which affects approximately 4% of the population in the world's developed countries. Previous studies have shown that insomnia may be "more prevalent and more strongly associated with the onset, severity, and recurrence of major depression," the authors wrote.

The current study is not the first time ventral striatum activity has been linked to depression. A previous study by Duke researchers, led by Ahmad Hariri, PhD, a professor of psychology and neuroscience and senior author of the current paper, discovered that ventral striatum activity could modulate the effects of stress on depressive symptoms.

"Lower activity in this area has been previously associated with greater depression risk, and deep brain stimulation of this area has been shown to help in treatment-resistant cases," Avinun explained to AuntMinnie.com. "We were, therefore, interested in examining whether activity in the same brain region also would modulate the negative effects of sleep problems on depressive symptoms."

In the study, the researchers collected data from 1,129 university students participating in the Duke Neurogenetics Study. The subjects had a mean age of 19.71 years (± 1.25 years).

Participants reported their own sleep patterns from the previous month using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The PSQI includes 19 measures by which respondents can subjectively assess sleep quality, duration, disturbances, daytime dysfunction, and other related variables. Scores range from 0 to 21, with a higher score denoting poor sleep quality.

The researchers also asked subjects to complete the Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (MASQ) to gauge their levels of depression. The MASQ assesses general distress/depression, general distress/anxiety, and anxious arousal. Higher scores indicate greater symptoms.

fMRI protocol

Each participant underwent an fMRI exam on a 3-tesla research scanner (Discovery MR750 3.0T, GE Healthcare) at the Brain Imaging and Analysis Center at Duke University Medical Center.

"The uniqueness of fMRI is in providing an indication of brain activation by looking at changes in blood flow based on relative levels of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin," Avinun said. "This means that we can see what's happening in a person's brain while they're completing a task and know which brain areas are more responsive to each stimuli presented."

During the fMRI scans, the subjects played a card-guessing game with positive and negative feedback designed to engage the ventral striatum. Participants had three seconds to guess an upcoming card's value by pressing a button. They were told they would receive a monetary reward at the end based on their performance in the game.

"After guessing, they received positive or negative feedback," Avinun said. "Importantly, the game was fixed, so all individuals experienced the same positive and negative feedback rates."

After analyzing the PSQI and MASQ scores and fMRI results, the researchers found that as activity in the ventral striatum increased, the link between sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms decreased.

"Very high ventral striatum activity ... dissociated the significant association between sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms," they wrote.

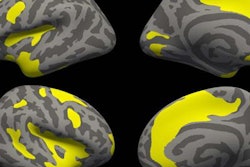

3D fMR image represents reward-related activity in the brain's ventral striatum. Participants with higher activity in this region were less likely to have symptoms of depression when experiencing poor sleep quality. Image courtesy of Duke University.

3D fMR image represents reward-related activity in the brain's ventral striatum. Participants with higher activity in this region were less likely to have symptoms of depression when experiencing poor sleep quality. Image courtesy of Duke University.In discussing possible reasons for the finding, the researchers noted a previous study that linked greater ventral striatum activity with feelings of optimism.

"It is possible that the individuals who appear to be more resilient to the adverse effects of poor sleep in our study -- those characterized by higher ventral striatum activity -- are more likely to have a positive outlook, view positive experiences as more rewarding, and cope better with negative experiences," Avinun said.