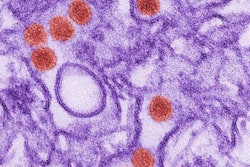

A new animal study published February 5 in Nature Medicine illustrates the challenges in detecting how the Zika virus affects the fetuses of infected mothers. Researchers found that the Zika virus caused injury to the brains of fetal macaque monkeys that was hard to detect with ultrasound and even MRI.

Zika sent chills throughout tropical regions when cases began appearing frequently in 2016, with Brazil being hit particularly hard. Most often spread by mosquitoes, the disease caused conditions such as microcephaly in infants born to infected mothers. While the outbreak has subsided since then, healthcare providers and public health authorities are keeping a watchful eye for its resurgence.

In the new paper, researchers from multiple centers described their efforts to detect the signs of Zika damage in the brains of fetuses by using tools including ultrasound and MRI (Nat Med, February 5, 2018). Knowledge of these signs could help providers counsel pregnant women with Zika infection, in particular for infants who are infected with the virus but who don't have the telltale signs of microcephaly.

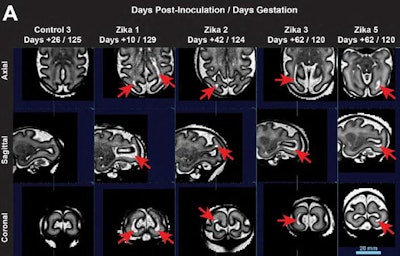

The researchers infected a test group of five pregnant pigtail macaque monkeys, while a control group of animals remained uninfected. They followed the symptoms that emerged after infection and performed regular imaging studies with ultrasound and MRI, in addition to using blood tests and other exams to track the progress of the monkeys and their fetuses.

Weekly ultrasound scans detected no obvious fetal abnormalities except for a periventricular echogenic lesion and ventriculomegaly in one monkey, the group found. Likewise, Doppler ultrasound scans of the middle cerebral artery in the fetuses showed no differences in the resistance index, which the researchers took to mean that fetal brain oxygenation was the same between the infected and control monkeys.

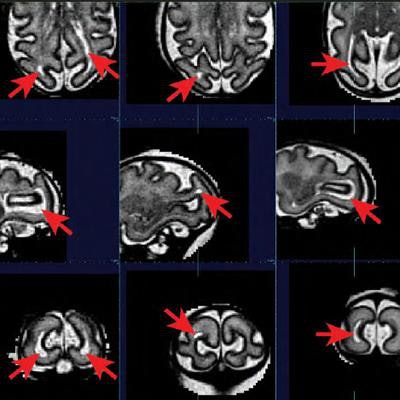

One imaging tool that did work was MRI with a half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo (HASTE) T2-weighted protocol. The technique revealed periventricular subcortical T2-hyperintense foci in the posterior brain in four of the five animals at 120 to 129 days of gestation, signs that were not found in the control fetuses. The brainstem and cerebellum otherwise appeared normal except for a cyst in one of the infected fetuses.

Researchers found telltale signs of Zika (periventricular subcortical T2-hyperintense foci in the posterior brain) on serial brain MRI scans with a HASTE protocol but said the phenomena were transient.

Researchers found telltale signs of Zika (periventricular subcortical T2-hyperintense foci in the posterior brain) on serial brain MRI scans with a HASTE protocol but said the phenomena were transient.The study shows the difficulty in detecting signs of brain injury in fetuses carrying the Zika virus, the researchers concluded. While T2-hyperintense foci were detected by MRI, the phenomenon was transient, and in any event MRI is not widely available in many regions where Zika is prevalent.

"Our study highlights the inability of standard prenatal diagnostic tools to detect silent pathology in the fetal brain associated with congenital Zika infection in the absence of microcephaly," they wrote.

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)