The simple tapping of one's fingers, while functional MRI (fMRI) monitors brain activity, could provide insights into the adverse effects of long-term excessive alcohol consumption, according to a study published April 27 in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research.

Because fMRI measures blood flow in the brain as it brings oxygen to cells, which then activate to perform tasks on command, researchers from Johns Hopkins University (JHU) have calculated the time between cell activation and task performance, also known as hemodynamic response function (HRF). Their data shows a slower HRF among people with a history of heavy drinking.

"Our results indicate that the shape of the hemodynamic response to a brief finger tap event changes as a function of the total alcohol consumed over the lifetime," wrote lead author John Desmond, PhD, professor of neurology, and JHU colleagues. "This may provide a biomarker for measuring changes in brain function resulting from chronic alcohol consumption."

Functional MRI is playing an increasingly valuable role in learning more about how alcohol consumption can adversely alter brain volume, inhibit motor and cognitive function, and foster binge drinking. While previous studies have shown that acute alcohol consumption can alter hemodynamic response function, scant information is available on how long-term alcohol abuse can affect the time between cell activity and motor response.

"Functional MRI task-related analyses rely on an estimate of the brain's hemodynamic response function to model the brain's response to events," Desmond and colleagues explained. "Although changes in the HRF have been found after acute alcohol administration, the effects of heavy chronic alcohol consumption on the HRF have not been explored, and the potential benefits or pitfalls of estimating each individual's HRF on fMRI analyses of chronic alcohol use disorder are not known."

This JHU study included 16 people with alcohol use disorder and 16 control subjects, all of whom provided their histories of alcohol consumption. The drinkers were divided into two groups: imbibers who consumed more than 50,000 drinks in their lifetime and those who took in fewer than 50,000 drinks. Subjects with alcohol use disorder were required to be abstinent for at least 30 days prior to the study's start. Their mean abstinence time was 93.3 months (range, 1.5-312 months).

Participants underwent 3-tesla fMRI scans (Achieva, Philips Healthcare) while performing 19 rounds of a finger-tapping exercise during which they alternately pressed two buttons with their right index and middle fingers for one second when prompting by a visual signal. The purpose was to measure HRF in the brain's left motor cortex, along with reaction time from the visual cue to the first button press for each tapping period.

Desmond and colleagues found no statistically significant difference between the three groups in initial responses to the visual cues, although healthy controls tapped more quickly (332 ± 107 ms) than the over-50,000 drinkers (321 ± 58 ms). However, the time between cell activation and task performance -- the HRF -- significantly increased in correlation with the amount of alcohol consumed over a participant's lifetime and was particularly notable in left sensorimotor cortex.

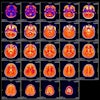

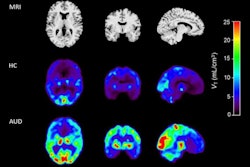

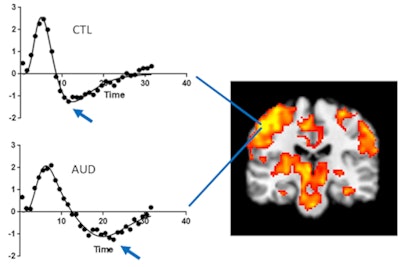

Functional MR image (right) shows activation, especially in left sensorimotor cortex, in response to the finger-tap task. The hemodynamic response function (HRF) charts (left) show average fMRI response to finger-tap event averaged over 19 trials for each healthy control subject (CTL) and each subject with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Arrows indicate main finding of slower HRF among AUD subjects, which significantly correlated with the number of lifetime drinks consumed. Image set courtesy of John Desmond, PhD, et al.

Functional MR image (right) shows activation, especially in left sensorimotor cortex, in response to the finger-tap task. The hemodynamic response function (HRF) charts (left) show average fMRI response to finger-tap event averaged over 19 trials for each healthy control subject (CTL) and each subject with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Arrows indicate main finding of slower HRF among AUD subjects, which significantly correlated with the number of lifetime drinks consumed. Image set courtesy of John Desmond, PhD, et al."Because the hemodynamic response is necessary for brain cells to be efficiently activated, the effects of alcohol consumption on the HRF could contribute to the behavioral and cognitive impairments associated with alcohol use disorder, and perhaps to difficulties in curbing drinking," the researchers concluded.