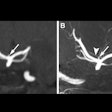

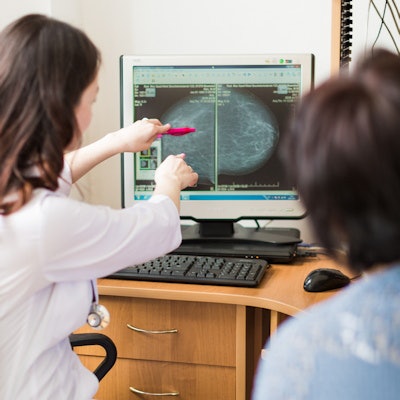

MRI-directed ultrasound has low success in detecting nonmass enhancement in women undergoing breast imaging, according to research published September 7 in Clinical Imaging.

A team led by Dr. Santo Maimone from the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, FL, found that ultrasound is more effective than nonmass enhancement is when evaluating for mass enhancement, especially with malignant masses or masses with irregular shapes or margins.

The group said their findings indicate that MRI-directed ultrasound needs fine-tuning and careful consideration by radiologists with the goal of eliminating unnecessary exams.

"Radiologists must choose wisely in determining the need for MRI-directed breast ultrasound, especially in women with new breast cancer diagnoses," Maimone and colleagues wrote.

MRI has the highest sensitivity of all breast imaging methods, but it also has inconsistent specificity. Lesions detected on MRI are often recommended for further evaluation with ultrasound and potential ultrasound-guided biopsy. Reported benefits for this approach include greater accessibility, reduced time, diminished cost, better access to superficial or deep locations, more accurate marker placement, and higher patient satisfaction.

"When employed appropriately, MRI-directed ultrasound can provide further information on enhancing lesions detected on MRI and allow efficient percutaneous sampling," the researchers said.

The team wanted to look at how MRI-directed ultrasound is used in breast cancer patients, saying that appropriate use is of "utmost importance" in these patients as they await triage to additional biopsy, surgery, or chemotherapy.

Data were pulled from 275 patients who underwent MRI-directed ultrasound for 361 breast lesions. Out of these, 187 (51.8%) were found on ultrasound. Of those detected, 171 were masses and 16 were nonmass enhancements, with masses 14 times more likely to be seen (p < 0.001).

While lesion size by itself was not a significant predictor of success, it achieved statistical significance when associated with lesion type (p < 0.001). Masses with irregular shapes or margins and invasive carcinomas were more frequently detected, with an odds ratio of 2.08.

Maimone and colleagues detected 33% of masses less than 0.5 cm and 57% of masses less than 1 cm, meaning that even small suspicious masses may be appropriately considered for MRI-directed ultrasound. However, the success rate for detecting lesions greater than 2 cm in size was low at 23.8%.

Patient age, internal enhancement pattern, and distribution of nonmass enhancements were not significant predictors in sonographic detection.

A presumed sonographic correlate for nonmass enhancements was found for 16 of 99 attempted lesions, a success rate of 16.2%. The researchers said this suggests that the threshold to perform ultrasound should be raised.

Invasive cancers, both invasive ductal and lobular carcinomas, were meanwhile significantly associated with sonographic detection compared to benign lesions.

The study authors said that adjusting the use of MRI-directed ultrasound will prevent inefficiencies and could help simplify surgical and oncologic management plans for patients with new breast cancer diagnoses.

"As MRI access and throughput increase, practices should reexamine their use of MRI-directed ultrasound and consider proportionally increasing MRI biopsy capacity to accommodate additional procedures," they added.