A tiny, wireless computer chip that uses ultrasound may be the future of monitoring the human body, able to be injected into the body to monitor processes in real-time, according to a study published May 7 in Science Advances.

A team of researchers from Columbia University in New York City have developed a computer chip the size of a dust mite that can be implanted into parts of the body and which uses ultrasound to monitor temperature, with the potential to measure more. The implant acts as a probe for real-time temperature sensing, including the monitoring of body temperature and temperature changes resulting from the therapeutic application of ultrasound.

The team's goal is to develop chips that can be injected into the body with a hypodermic needle and then communicate back out of the body using ultrasound, providing information about body characteristics they measure locally.

"We are working on ideas that allow devices like these to augment ultrasound by providing information within an ultrasound image that cannot be conveyed endogenously, like pH, temperature, identification and quantitation of small molecules and proteins," said senior author Kenneth Shepard, PhD.

There is growing interest for wireless, miniaturized implantable medical devices that can detect body processes such as temperature, blood pressure, glucose, and respiration for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. However, conventional electronics usually require multiple chips, packaging, wires, and external transducers. Batteries are also often needed for energy storage.

Traditional radiofrequency communications links are not possible for a device on the micro level because the electromagnetic wavelength is too large relative to the size of the device. However, by using smaller ultrasound waves instead, the team can power and communicate with the device wirelessly via an antenna on top of the chip.

"Our motes [chips] have the potential to be adapted to the distributed and localized sensing of other clinically relevant physiological parameters," the team wrote.

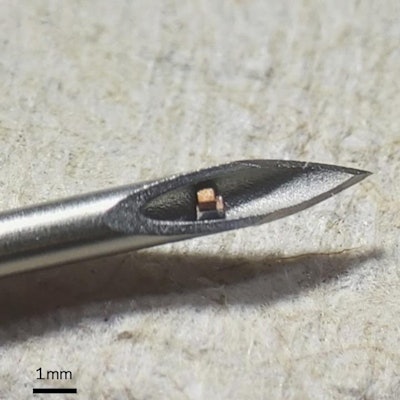

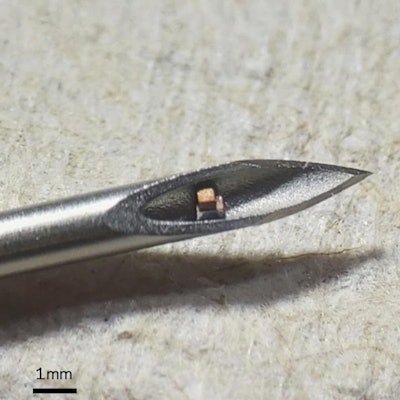

The chip has a total volume of less than 0.1 mm3, viewable only by microscope. The small size allows the chip to be implanted or injected using minimally invasive techniques with improved biocompatibility. The chip system proved successful in mouse models, according to the team's study, with the device not artificially heating tissues surrounding it.

Columbia University engineers have developed a single-chip system that is a complete functioning electronic circuit. These chips can be injected into the body with a hypodermic needle to monitor medical conditions. Image courtesy of Chen Shi and Columbia Engineering.

Columbia University engineers have developed a single-chip system that is a complete functioning electronic circuit. These chips can be injected into the body with a hypodermic needle to monitor medical conditions. Image courtesy of Chen Shi and Columbia Engineering."Functionality at greater tissue depths could be achieved with further reduction in the device power consumption, a reduction in the ultrasound operating frequency, and the application of two-dimensional ultrasound imaging array for more effective focusing of ultrasound energy to the implanted motes and more effective capture of the backscattered signals," the team wrote.

The authors are calling this the world's smallest single-chip system that is a complete functioning electronic circuit.

Shepard told AuntMinnie.com that the team has plans to work toward human trials, but it will need an investigational device exemption from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration before trials can proceed.