The September 11 terror attacks in the U.S. have prompted hospitals and radiology departments to take a hard look at disaster recovery. This three-part series examines what can be done to enhance disaster preparedness, and provides suggestions and examples of how to protect and recover digital images and data in case of disaster.

Most New York City healthcare facilities were not damaged or compromised on September 11. The exception was NYU Downtown Hospital (Beekman), which was just four blocks from the World Trade Center site and suffered power and telephone interruptions because the nearby ConEd power station was destroyed. The hospital is not a trauma center, but nearly 1,000 victims were treated there that day. Most of the victims who made it to the hospital had minor injuries and did not need x-rays.

Beekman’s chief of radiology, Dr. Hyman Shwartzberg, said the hospital is mostly film-based and doesn't really have a PACS. Standing in the ER looking at monitors to give real-time interpretations meant radiologists sometimes got in the way of emergency staff. The hospital already has plans for a PACS, however, and if it had been in place on September 11, Shwartzberg said, his crew could have stayed out of the way, working elsewhere in the hospital or even from home.

The hospital held twice-daily briefings to compensate for the sporadic phone outages. On the day after the attacks, Beekman got a CT scanner with its own generator.

For most other New York City hospitals, emergency personnel were mostly left standing and waiting for patients who never came.

Bellevue Hospital in southeast Manhattan closed its outpatient radiology service that day, and took only trauma patients who walked into the ER. They saw about 30 of those from the WTC site. The hospital has several image stations for clinicians, and set up a second dedicated station in the ER with a large monitor for a radiologist.

Bellevue’s emergency physicians had access to the PACS within the trauma bay itself, and at other sites in the emergency department. Dr. Philip Jeffery, Bellevue’s director of emergency radiology, said those stations have 1K monitors, which aren't considered good enough for radiologic diagnosis. Radiologists read off larger 2K monitors. Jeffery said they could have had people reading at almost any site away from the ER, if they had had a more extensive PACS network in place.

Bellevue moved three ultrasound machines into the ER to look for blunt abdominal trauma and/or free fluid in the abdomen so patients wouldn’t have to go to CT, but given the small number of trauma patients who showed up, these scanners were not very useful.

Jeffery said Bellevue’s disaster plan is somewhat out of date, as it didn’t cover the PACS. The plan is being revised.

At Manhattan's Beth Israel Hospital on September 11, Dr. Lee Sider focused single-mindedly on the acute care of his patients. He had some concerns over whether an influx of patients would overwhelm the hospital’s ability to assign them with medical record numbers, which are required to track patients with the hospital’s PACS network. He said he was willing to chuck the PACS and go with old-fashioned film-based images if it would help get the patients tracked and treated.

But it wasn't necessary. Although most of the patients who came in that day were not in Beth Israel’s system, the hospital’s admissions process was not overwhelmed. About 300 patients acutely needed x-rays, and the hospital was able to continue to assign them with medical records and use its PACS network to archive those images digitally.

Sider said Beth Israel hadn’t considered having an offsite backup mirror system for images and data, but is looking at one now. The biggest change is that Beth Israel will incorporate plans to deal with biological and chemical terrorism.

New York City’s public hospitals are part of the Health and Hospitals Corporation (HHC). HHC is an example of what some large networks are doing, having created its own centralized, offsite network on Manhattan’s 41st Street, where all data is backed up and security measures control access. The Manhattan hospitals in this system are Harlem, Renaissance, Metropolitan, Gouverneur, and Bellevue.

HIPAA on the horizon

One hundred years ago we didn’t know we needed telephones. Five years ago we didn’t know we needed cell phones. Ten years ago we didn’t think we needed to back up our archive of film images.

Film was never backed up, and the cost of doing so now would be prohibitive. The advent of digital radiology has been accompanied by a resulting search for ways to store tens of thousands of archive-intensive images. Things are made more complicated by the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Although the major disaster medicine journals generally fail to cover RIS/PACS networks and their possible failure in case of massive internal disaster, government and professional mandates that cover these events are being put in place, and all healthcare providers -- from huge medical centers down to solo practitioners -- will have to develop appropriate manuals and procedures.

Ironically, until the technology was created to back up archives, the procedure wasn't required, or even done. And despite the fact that facilities have begun the migration from analog to digital archiving, the world is still split in two: half paper or film, and half electronic. As a result, radiology departments are managing different media -- paper, film, and soft copy.

HIPAA will require those healthcare providers that maintain or transmit health information electronically to provide reasonable and appropriate safeguards to ensure confidentiality and protect the information against all reasonably anticipated threats or hazards. HIPAA calls only for recommendations on electronic medical records. There, the act does not require the development of a standard.

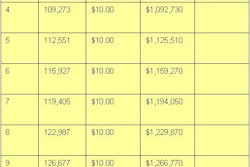

One HIPAA consultant estimated that a capital budget (including capitalized labor costs) for an integrated healthcare information system generating $1 billion to $2 billion in revenue is $75 million to $275 million. In a time of budgetary penny-pinching, finding the money for information systems can be a challenge.

HIPAA applies only to digital information, so if you’re in a film environment, you can continue to operate without backup. Moving to a digital environment, however, will require the maintenance of backup copies of all data.

The HIPAA definition of what constitutes a medical record is murky. For instance, a radiological image is not a part of the permanent patient record, but the written report is. On the other hand, if there is no report, then the image becomes the official record.

Even solo-practice radiologists will need to maintain manuals and procedures to remain in compliance with HIPAA. One solo physician in the small town of Ukiah, CA, Dr. Jens Vinding, stores all of his digital images on optical disks and takes them at night to a backup system at his home. Physically carrying backup disks to a secure offsite storage location is an inexpensive solution that works.

At this point, however, Vinding has little need to provide Internet access to referring physicians. Recently he asked about 40 of them whether he should build a server so they could access patient studies -- and only two physicians were interested. The rest still preferred hard copies.

By Robert BruceAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

January 24, 2002

Next week: JCAHO standards on developing an emergency preparedness plan.

Related Reading

Disaster recovery case study #1: The Dallas VA alternative

Disaster recovery case study #2: UCSF’s model for PACS recovery from off-site storage

Disaster recovery in radiology, Part I: Protecting your images and information, January 17, 2002

A roadmap for implementing HIPAA in radiology, July 26, 2001

Bibliography

"Definition of the health record for legal purposes," American Health Information Management Association, October 2001, Volume 72-9.

"Disaster planning for health information," American Health Information Management Association, May 2000, Volume 71-5. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

"Hospital resources for disaster readiness," American Hospital Association, November 1, 2001.

"Mobilizing America’s healthcare reservoir: emergency management in the new millennium." Special Issue of Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations Perspectives, December 2001, Volume 21, Number 12.

"Picture archiving and communication system (PACS) security plan," Ward M. Terry, Dallas Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Dallas, April 2000.

"Plan for the worst before disaster strikes," Hospital Management Technology Magazine, June 2000.

"Protecting the privacy of patients’ health information," HHS Fact Sheet, Department of Health and Human Services, July 6, 2001.

"Simulation of disaster recovery of a picture archiving and communications system using off-site hierarchal storage management," David Avrin et al, Journal of Digital Imaging, Vol. 13, No. 2, Suppl. 1, May 2000.

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com