A 75-year-old woman had suffered head trauma from a fall, and her CT scan at a rural Alabama hospital reportedly showed parenchymal blood. Because the ER physician was unsure of management, the patient was sent on a two-hour ambulance ride at 1 a.m. But that trip could have been avoided with an image exchange network.

After the patient was preadmitted to the intensive care unit at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), she was found to have a normal CT exam. Following simple observation, she was discharged -- but after incurring preventable cost to family and payors.

In a presentation at last month's Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine (SIIM) meeting, Dr. Barton Guthrie shared how the burgeoning Central Alabama Health Image Exchange (CAHIE) hopes to prevent that scenario from happening again.

In another recent example, UAB received a phone call from an Alabama town regarding a 45-year-old man with an inner ear infection and possible intracranial involvement. He was awake and alert. The neurosurgeon requested advice on whether he should be involved in this case.

The patient was transferred two days later in a comatose state and required emergency drainage of a posterior fossa abscess. He experienced a prolonged hospital stay, rehabilitation, and assisted care, not to mention the lost income, family grief, reduced work productivity, and enormous cost to the payor, Guthrie said.

"Had we been able to see the [image] at the time of the phone call, this patient would have been walking and talking and essentially normal," he said. "We would have been able to intervene quickly and have him back to work, and avoided tens, maybe hundreds of thousands of dollars of cost to the payor, not to mention the lost income."

Image sharing

While image sharing would seem to offer much clinical benefit and cost savings, it can be tricky to determine who is responsible for setting up an image exchange network, and how to pay for it.

"Should the provider do it, or should the hospital be responsible for sending out information to patients? Should patients be responsible for gathering all of their data and bringing it with them? Should the payors be responsible?" he asked. "I'm not sure there's an answer, but how you feel about those questions is extraordinarily relevant to how you structure your image sharing approach."

At UAB, images from 12,000 patients each year are inaccessible, and 3,500 emergency patients are transferred without images. UAB spends $150,000 managing CDs. And then there are the soft-dollar costs, such as expenditures secondary to poor initial care and the loss of work hours, he said. It's also risky to repeat imaging studies due to increased radiation exposure.

In an attempt to tackle this problem, the institution submitted a proposal to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). The NIH's National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), which also funded the RSNA's Image Share project, provided a grant to fund an image exchange network for a six-hospital consortium in the state.

The exchange is based on the Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) Cross-Enterprise Document Sharing for Imaging (XDS) protocol, and it consists of UAB Hospital, Children's Hospital, Medical Center West, Cullman Regional Medical Center, Montgomery Baptist, and Cooper Green Mercy.

CAHIE goals

The goals for CAHIE included offering query access to image data, minimal image data communication time, a maximized provider-patient encounter, and reduced cost. The system also sought to provide cross-hospital, real-time image access, Guthrie said.

The six-hospital consortium also wanted to use a Web portal for providers and patients, and it wanted the system to be scalable and use standards. It also had to include infrastructure for value-added services and needed to be sustainable, he said.

The project included a prime contract awardee -- UAB -- and five subawardees. In the first year of the project, policy issues were worked out, covering privacy and consent, data use, standard operating procedures, and security.

"The technology it turned out was not too difficult," he said. "The difficult thing was the policy."

As a guiding principle, hospitals would retain their own data instead of sending the information to a central data repository.

"We wanted all the data locally and wanted to be the stewards of quality," Guthrie said.

That principle led to the use of a federated model. Year 2 of CAHIE led to the development of a request for information (RFI) and request for proposal (RFP) that included detailed system specifications, which can be accessed here. Installation of system interfaces (the edge servers) at each site then began, and system testing took approximately one to two months per site.

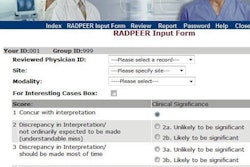

The edge server at each participating hospital ran the system's core infrastructure, which is provided by health IT firm MEDecision. This infrastructure offers a centralized registry, electronic master patient index, access controls, and an audit trail. DICOM studies can be pushed or pulled to any of the local hospitals and accessed via the Web viewer.

Following the completion of security testing and system acceptance, the network is expected to go live this week. In the third year and in the future, CAHIE will gather data on metrics, such as performance and impact on care.

Current status

The focus now is on sustainability, including looking at possible partners, Guthrie said.

Obstacles to the success of the project include the conflict of local revenue drivers with the global solution. Duplicate imaging actually makes money for institutions, so chief financial officers might not be pleased to hear that radiology output might decline 5% due to the image sharing network, he noted.

Other less-difficult obstacles include the participation of regional radiology referral networks, in which hospitals pay for workstations and networks for affiliate hospitals in exchange for having images sent to them to read.

"It's a terrific business model, but it's a little bit of an antithesis to global access at the point of patient care," he said. There also needs to be accountability for data sharing.

If CAHIE can be sustained, the network's beneficiaries would include payors. Discussions are under way with payors over a proposal to fund a two-year pilot for selected hospitals, according to Guthrie.

Other potential beneficiaries include self-insured Alabama businesses, and the team has also written a number of government grant applications.

Success for the network depends on a high level of cooperation between prospective partners, and managing conflict between local and global revenue drivers, Guthrie said.

"Ultimately, I think the way we can get this thing paid for is through beneficiaries," Guthrie said.