NATIONAL HARBOR, MD - Embedding patient photos into medical images has already been shown to prevent misidentification. Now, a new survey shows that the idea has broad support, although some radiologists have concerns about the practice, according to research presented on Saturday at the Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine (SIIM) meeting.

The group from Emory University asked healthcare providers and the parents of pediatric patients about the idea of placing a photo of a patient's face in the corner of a chest radiograph or other imaging study. Large majorities of the parents and nurses surveyed were on board with the idea, but only 63% of radiologists believed photo IDs would result in more accurate interpretation of images.

"Overall, a large majority of nurses, technologists, and radiologists support the technology," said Dr. Gelareh Sadigh in her SIIM presentation. Still, some radiologists "considered it a distraction in the clinical setting" and want to hold off on full implementation until they get a sense of how photo embedding works in practice.

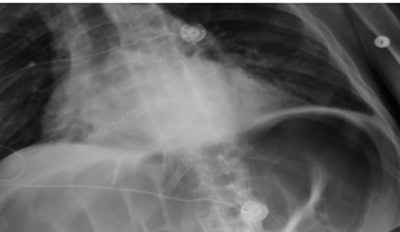

Patient photograph (lower left) facilitates correct identification of the chest radiograph. Image republished with permission of the American Roentgen Ray Society.

Patient photograph (lower left) facilitates correct identification of the chest radiograph. Image republished with permission of the American Roentgen Ray Society.A heavy toll

Despite concerted efforts to stem the tide of patient errors, the phenomenon remains a serious problem in medical practice. As many as 400,000 patients in the U.S. die each year from medical errors, Sadigh said. And although few radiology studies are available, a Pennsylvania study found that in that state alone there were 652 radiology event reports during 2009, one-third of which were due to wrong-patient events. At Emory, four near-miss wrong-patient events are reported for every 100,000 patients, according to Sadigh.

"If even one of those errors causes harm, it can result in a lawsuit and other negative consequences," she said.

Dr. Gelareh Sadigh from Emory University.

Dr. Gelareh Sadigh from Emory University.To help avoid such misidentification errors, Joint Commission guidelines call for at least two patient identifiers before providing care, such as name, birthday, assigned identification number, and telephone number or address.

For the current study, the idea was to add a photograph that was inseparable from the patient's medical image, and the researchers also wanted to determine if the photographs were acceptable to the various providers involved in the patient care process. Technology developed at Emory embeds the photograph directly into the DICOM images using a camera installed on the x-ray system.

"When the x-ray tech triggers the machine, we get an x-ray from the patient and the camera gets a photo of the patient that includes the cassette ID plus the time stamp of the time the image was obtained," Sadigh. "All three -- the photo, the ID, and the time stamp -- go to a server and the server makes a DICOM image out of it."

The group determined previously that attaching a photograph to the images reduced wrong-patient errors and was even more critical -- and potentially the only identification -- for unconscious patients.

However, considering the privacy implications, ascertaining the social acceptability of the practice is important before adopting it as the standard of care.

"In order for a technology to be considered useful, it should also be socially acceptable," Sadigh said.

The investigators queried several stakeholder groups to determine if they would accept the addition of a photograph to patient medical images. Levels of agreement were scored on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 reflecting the highest level of support. The five levels were then collapsed into dichotomous agree/disagree weighted responses, depending on the strength of agreement or disagreement.

Bowel perforation from a wrong-patient error; above, image of patient on first day. Below, image of a different patient sent in error to the first patient's folder. Bottom, image of first patient developing bowel perforation as a result of error. All images courtesy of Dr. Gelareh Sadigh.

Bowel perforation from a wrong-patient error; above, image of patient on first day. Below, image of a different patient sent in error to the first patient's folder. Bottom, image of first patient developing bowel perforation as a result of error. All images courtesy of Dr. Gelareh Sadigh.Parents and guardians

The first group surveyed consisted of parents and legal guardians of pediatric patients. They were asked 13 questions in a hospital waiting room about their attitudes toward photographs attached to images if the photos were shown to reduce the chances of misidentification. The questions were divided into three areas: perceptions of the value of technology in improving patient safety and care; worries about negative aspects of the new technology, such as privacy concerns; and demographic characteristics.

In all, 498 of the 600 parents (mean age, 37; 86% female; mean child age, 7 years) responded. Most were enthusiastic about the concept of photo IDs. Overall, 96.5% (476/493) said they would accept the technology if it helped doctors interpret medical images better. But 38% worried that a photo would hurt their child's privacy, and 98.3% said they should be asked for their consent before a photo is taken.

Radiologists

An online survey was also sent to faculty and residents in diagnostic radiology, interventional radiology, and nuclear medicine.

Forty-nine (63%) of the 78 responding radiologists (mean age, 40; mean years in practice, 11; 40% residents) said photo IDs would result in more accurate interpretation. Thirty (41%) of 74 radiologists said the photos would result in better interpretation of lines and tubes, and 52% said photo IDs would result in more accurate identification of mislabeled patients.

However, 49% of radiologists said they feared the photos would result in more time being spent on interpretation, and 33% said they would feel more distracted with photo IDs.

Technologists and nurses (86% female; mean years in practice, 14) answered the survey at rate of 59% (50/84). Overall, their support was "somewhere between parents and radiologists," Sadigh said, with 71% believing that photos would improve image interpretation, 59% saying they would decrease interpretation time, and 73% saying they would reduce mislabeling errors.

As for limitations, the study looked only at stable patients brought to radiology, not intensive care unit or trauma patients, Sadigh said. Also, no adult patients were surveyed, and there may be a sampling bias among radiologists and technologists, owing to the tendency of people who feel strongly about something not to offer their opinions.

Overall, a large majority of parents, radiologists, and technologists support the use of photographs; however, there are concerns among radiologists that the photos could be a distraction, Sadigh concluded. A general consent form may be sufficient to cover the requirement for consent noted by the parents, she added, as it includes permission to photograph.

Several questions remain, for example, whether photographs should correspond to the anatomy imaged rather than just faces, and whether the photographs become for legal purposes a medical image, Sadigh said in a discussion with SIIM session moderators.