Canada's imaging services system has often been held up by its U.S. critics as an example of how a government-run health system stifles technology innovation and diffusion. One commonly used factoid from the 1990s claimed that there were more MRI scanners in Orange County, CA, than in all of Canada.

Some of those problems have persisted. Among the troubling vital signs:

In a widely publicized case, Ryan Oldford, a 4-year-old boy in the Atlantic province of Newfoundland, faced a two-and-a-half year wait for an MRI.

A judge in the province of Quebec has allowed a class-action suit against the provincial government and local hospitals, in which women are arguing that access to radiotherapy after breast cancer surgery was too slow.

Canada remains below the median of industrialized countries in access to imaging services, according to a new report.

But the time of death hasn't been called on the faltering system yet. Canada has made encouraging progress in upgrading its installed base of imaging equipment, and vendors say they've seen a growth in sales, a view supported by a January report on imaging from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

Medical Imaging in Canada, 2004 stated that Canada had 151 MRI scanners at the beginning of 2004, more than four times the 40 it had 10 years ago and up from 144 in 2003. The number of CT scanners has also risen during the last decade, from 234 to 338, according to the CIHI report.

Last month, Ontario -- the country's most populous province -- announced it will spend $120 million Canadian dollars to buy new CT and MRI machines, expand operating hours, and add additional radiotherapy equipment.

"The patient is out of the ICU, but not out of the woods yet," said Normand Laberge, executive director of the Canadian Association of Radiologists (CAR). Despite dramatic problems like the Oldford case, Laberge said the Canadian radiology system appears to be slowly improving, even though waiting lists are still long, manpower still short, and equipment still not readily accessible in all parts of the country.

Canada still does not rank highly in terms of access to imaging equipment. Canada had 4.6 MRI scanners and 10.3 CT scanners per million people. Among 21 industrialized nations reporting data on imaging equipment, Canada holds spot number 13 for MR scanners and 16 for CT. By comparison, the U.S. had 19.5 MRI scanners and 29.5 CT machines per million people.

Overall, Laberge said, the picture is encouraging, even though some parts of the country lag behind.

Newfoundland, for instance, has a single MRI machine for its roughly 530,000 people, which is how Ryan Oldford -- who needed a preventive scan to ensure that his kidney was free of precancerous cells -- wound up in a 30-month waiting list.

Ryan's hope

The boy has already lost one kidney to cancer. His doctor suspected that he had a rare syndrome, putting Oldford at higher risk for leukemia and cancers of the kidney and liver. But that wasn't enough to move him to the head of the waiting list.

"It's a nonurgent case, but to have a two-and-a-half year wait -- even for a nonurgent case -- is ridiculous," Laberge said. After weeks of outcry, Ryan received his MRI scan on February 2, after another patient cancelled.

Outside of Newfoundland, Laberge said, the wait for a boy like Ryan would have been between three and four months -- "not that good, but not really all that bad," he added.

CAR is aiming to get the wait down to under a month for nonurgent cases, according to Laberge. "That's what the evidence suggests" is acceptable, he said.

Timely access to care is an issue that may be at least partly settled in the courts. Last year, Quebec Superior Court Justice John Bishop allowed a class-action suit to be brought on behalf of 10,000 breast cancer patients who claimed they had to wait too long for radiotherapy (Canadian Medical Association Journal, May 25, 2004, Vol. 170:11, p. 1655).

The suit was filed at the request of Anahit Cilinger of Montreal. Cilinger had a partial mastectomy with lymph node removal in October 1999, but was wait-listed for radiotherapy. Twelve weeks later, Cilinger was still waiting, so she flew to Turkey for her treatment.

The delay was caused by a provincial government decision to cap funds available to radiotherapy, which led hospitals to extend waiting times, Laberge said. The court is being asked to decide if the decision carries any liability, and also whether real damage resulted from the delays, he said.

It will probably be easier for the plaintiffs to win the first part of the suit than the second, he said, "but even that would send a very strong signal" that waiting lists must be shortened.

Observers are also watching the Supreme Court of Canada very closely for a ruling in the case of Dr. Jacques Chaoulli and patient George Zeliotis, who argued that long delays in hip-replacement surgery violated his rights under Canada's constitution. The case was heard last summer, and a ruling is expected later in 2005.

"These cases are redefining what we mean by universal healthcare," Laberge said.

Better technology; a dose of digital

Part of the solution to reducing wait times is a wave of new equipment being installed. This growth in sales has been driven by the 2004 health accord between Canada's national government and the 13 provinces and territories. The accord established a $4.5 billion fund to reduce wait times for several services -- including diagnostic imaging and radiotherapy.

"I think we've seen double-digit growth, about 10% (over the past couple of years), but it's not linear -- we see spurts of investment," said Joe Sardi, general manager for GE Healthcare in Canada.

Alain Provencher, MR product manager for Siemens Canada, said increased investment in new equipment, as well as replacement of older machines, has resulted in better access overall.

"In the past two or three years, there has been a major effort to catch up," Provencher said, even though, as the CIHI report shows, the catch-up has fallen short.

One benefit of new equipment is that it is often faster and easier to use than older machines, increasing patient throughput, Sardi explained. But new equipment isn't the whole answer, Laberge said. CAR is arguing that the radiology system has to work smarter to overcome some structural problems, such as a shortage of manpower.

Currently, Canada has 1,902 trained radiologists, although not all of them are full-time employees. There is also a shortage of technologists. In response, CAR is urging the use of "physician extenders" to take some of the load off doctors.

"We want to apply the nurse-practitioner model to radiology," Laberge said.

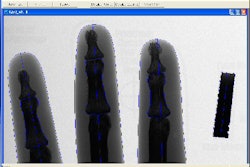

More widespread use of PACS and RIS is under way in the country as well. Currently, about 27% of imaging in Canada is digital; the goal is to reach 80% within a few years.

Finally, CAR's leaders would like to see the demise of unnecessary imaging, Laberge stated.

"We estimate 5% to 7% of the imaging we do is not appropriate," Laberge said. For example, a patient who falls and has bruised ribs will almost certainly get an x-ray. But since the treatment is the same for a bruise, a sprain, or a fracture, the x-ray is a "waste of time and money," he said.

National healthcare pains

While other countries may applaud Canada's public healthcare system, there is no denying that it is an overburdened one. Long waits are not just associated with MR scans. To obtain a PET scan that is paid for by the healthcare system, patients must wait for one of four public machines in Quebec.

The imaging logjam could be eased if patients were reimbursed for using private clinics, according to Steve Stein, director of operations for Ville Marie PET and CT Centre, a private imaging clinic in Montreal. Stein said he's "more than willing" to help fill the gap, but there's no mechanism that allows doctors to send patients to his clinic and have the service paid for by public system. Instead, patients must pay out of their own pockets or use private health insurance.

Canada's governments need to commit themselves to public-private partnerships, said Illich Cheng, president of MRI scanner developer Millennium Technology of Richmond, British Columbia, just outside of Vancouver.

"There is a huge demand in Canada for radiology equipment," Cheng said. If public-private partnerships were "endorsed by government, that would to help the Canadian health system."

By Michael Smith

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

February 24, 2005

Related Reading

Brain tumor treatment inconsistent in U.S. and Canada, February 3, 2005

Hitachi Canada enters diagnostic imaging market, November 18, 2004

Agfa brings RIS to U.S., Canada, October 19, 2004

Technology seen key to Canada's health-care ills, September 15, 2004

Copyright © 2005 AuntMinnie.com