Private-practice veterinarians have long relied on ultrasound and x-ray as diagnostic tools to assist in the care of their patients. And as is the case in human imaging, these two imaging techniques are just one part of the wide range of services a vet practice provides, from surgery to dentistry.

Just as radiologic technologists (RTs) provide much of the hands-on care in the imaging suite, veterinary technicians serve a similar role in the companion-animal practice. Transitioning from the human world of an RT to the animal kingdom of a vet tech is not a huge leap, but the jobs are distinctly different, and the salary is likely to be far less.

Vet technicians provide professional technical support to veterinarians by performing physical exams, collecting patient histories, educating clients, caring for hospitalized patients, administering medications and vaccines, taking and developing x-rays and ultrasound scans, administering anesthesiology, assisting with surgery, and conducting clinical lab procedures.

Careers in veterinary technology require a minimum of two years of college education, acquired at one of approximately 80 colleges across the U.S. offering programs accredited by the American Veterinary Medical Association. Some vet tech programs can lead to a bachelor’s degree. In the 40 states where certification is required, graduates must pass a credentialing exam, administered by the State Board of Veterinary Examiners, or the appropriate state agency.

|

| Actress Linda Blair (The Exorcist) soothes the savage beast -- in this case, 390-lb Bengal tiger Katie who is about to undergo a CT scan. Veterinary radiologist Dr. Jean Reichle looks on. Image courtesy of Animal Imaging of Los Angeles. |

The umbrella organization for vet techs in the U.S. is the National Association of Veterinary Technicians in America. The association offers continuing education and employment-related information on its Web site, as well as links to accredited programs across the U.S.

According to NAVTA, about 85% of graduate veterinary opportunities are in private veterinary practice, primarily companion-animal practices catering to dogs and cats.

The average salary of an experienced, credentialed, full-time veterinary technician is $24,323. In a survey conducted by NAVTA in 1999, the salary range spanned $10,000 to $40,000 for recent graduates. Typical hourly pay is between $10 and $15 an hour.

|

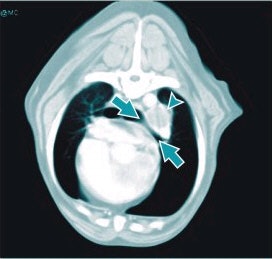

| Libby the Rottweiler had an undifferentiated sarcoma of the left foreleg that recurred after excision. A CT of the thorax revealed an enlarged tracheobronchial lymph node (arrowhead), which caused compression of the left mainstem bronchus (arrows). Image courtesy of Animal Imaging of Los Angeles. |

Unlike RTs, whose jobs revolve around preparing patients for imaging, performing imaging exams, and providing some patient education, imaging is but a small part of the average vet tech’s job. A typical position demands experience in client communications, endoscopy, pharmacology, cytology, dentistry, surgical assistance, and ultrasound.

"In veterinary medicine, to the best of my knowledge, there is no designation for individuals who are purely performing diagnostic imaging," wrote Dr. David Wright in an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com. Wright is a professor of veterinary technology with the Distance Education Veterinary Technology Program in Lancaster, TX.

There is a role for trained RTs in veterinary practice, but currently, opportunities are limited to university teaching hospitals and a handful of specialty imaging clinics where more advanced imaging tools, such as spiral CT and MRI, are being used.

"At the moment, careers for RTs in veterinary medicine are generally limited to academic institutions and very large referral practices," said Dr. Eric Wisner, president of the Davis, CA-based American College of Veterinary Radiology, and a professor of veterinary medicine at the University of California, Davis. "But as diagnostic imaging continues to become an increasingly important part of veterinary practice, I think we will see new positions open up in smaller specialty practices as well."

In addition to teaching hospitals, animal imaging jobs for RTs may also exist in specialty clinics. In the past year alone, two new animal imaging clinics opened on opposite sides of the U.S., specifically to cater to companion animals. In March, pet-food manufacturer Iams Company of Dayton, OH, announced the opening of an MRI center in Vienna, VA, to provide high-end imaging to the region’s pets.

At the center, onsite veterinarians supervise procedures, which are performed using a scanner from multimodality vendor Siemens Medical Solutions of Iselin, NJ. Iams contracts with imaging services firm ProScan Imaging of Cincinnati, OH, to provide the technical and veterinary medical staff to perform and interpret the MRI studies.

Pet owners need a referral from their veterinarian, who makes an appointment at the MRI center. Scan results are conveyed to the veterinarian within 24 hours. Cost for the animal scan averages $1,200.

In July, the West Los Angeles Animal Hospital opened its companion center, Animal Imaging, which features MRI and CT. The large practice boasts more than 40 vet technicians and assistants, according to Dr. Jean Reichle, a veterinary radiologist and hospital director.

"We do have RTs who operate the CT and MRI machines," Reichle said. "The vet techs monitor the patients, who are under anesthesia for the exam. While our equipment is of course designed for humans, we need to be crafty: for example, we use the knee coil for MRI of the dog brain."

The Los Angeles center caters to animals both large and small, and announced its opening during a media event that involved an MRI scan performed on a 390-lb Bengal tiger -- an animal actor.

|

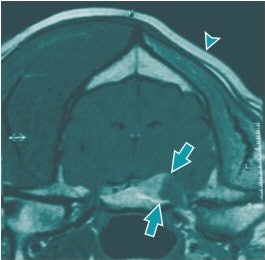

| An MRI of an 8-year-old golden retriever dog. Buzzie presented with weight loss and severe left-sided facial muscle atrophy (arrowhead). The MR exam revealed a partially contrast-enhanced tumor of the trigeminal nerve (CNV, arrows) that is evident within the cranial vault and exits through the foramen at the level of the temporomandibular joints. Image courtesy of Animal Imaging of Los Angeles. |

Most RTs who are working in veterinary teaching hospitals hail from both the human and animal professions, Wisner said.

"As you might expect, whether the person is an RT just getting into veterinary medicine, or a vet tech newly learning about imaging, there is quite a bit of on-the-job training required," he said. "At UC Davis, we now have vet techs who are trained in CT, MRI, nuclear medicine, ultrasound, and large and small animal radiology."

Imaging workflow at the teaching-hospital level is not much different than in human practice, he said. Technologists generally perform the studies, and veterinary radiologists interpret them.

At Louisiana State University’s school of veterinary medicine in Baton Rouge, all imaging work is performed by trained RTs, according to Dr. Robert Pechman, professor of veterinary clinical science.

"I have a colleague who feels he can teach a vet tech about radiology faster than he can teach an RT about veterinary anatomy," he said. "My experience has been just the opposite. The techs that have worked with us learn the correct anatomy, positioning, and techniques quickly, and are more knowledgeable about safety than vet techs -- so everyone is better off."

Moreover, he said, when a special protocol or view is needed in order to see a structure, Pechman said that RTs are better able to find a view that works than vet techs who also perform imaging.

"It’s possible that as specialty radiology practices grow in number, there may be more opportunities for RTs," Pechman said. "But my sense is that in general veterinary practices, the cost of an RT will be too great to find much employment."

That thought is echoed by another veterinary physician, who works as a consultant to veterinary practices but asked not to be named.

"Unless an RT is in a veterinary teaching hospital, their skills will not be used to the fullest extent," she said. "And they will need different kinds of skills, such as animal restraint and anesthesia. While it would be fun for an RT to go into animal imaging, this is not an area with huge numbers of jobs or lots of opportunity. The work includes a whole lot besides radiology, and the pay is definitely lower than human medicine."

By Deborah R. DakinsAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

November 7, 2002

Additional reporting by Monica L. Lewis.

Resources

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

Distance Education Veterinary Technology Program

National Association of Veterinary Technicians in America

University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine

Related Reading

GE, Sound Technologies partner for vet market, February 15, 2002

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com