Colombian radiologists are forging ahead when it comes to the implementation of laws and regulations specific to the exercise of radiology and diagnostic imaging. The legislative Act 657 of 2001 governing the practice of radiology in the South American nation is something of an anomaly in the Americas. Even the U.S., which operates under the Stark Law regulating issues concerning medical practice, does not have a similar law specific to the practice of radiology.

"There is a marked difference in the way we operate since the law 657 of 2001 came into force, optimizing all spheres of professional work for radiologists," noted Dr. Rodrigo Restrepo from the Medellin Clinic, Medellin, who was head of the Asociación Colombiana de Radiología when the Act 657 of 2001 came into law. "There is a greater sense of identity and confidence within the radiology community in Colombia."

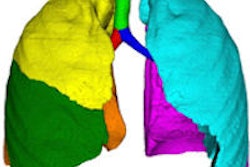

Leading hospitals in Colombia make use of the latest software to visualize and analyze 2D, 3D, and 4D images. All images courtesy of the Asociación Colombiana de Radiología.

Leading hospitals in Colombia make use of the latest software to visualize and analyze 2D, 3D, and 4D images. All images courtesy of the Asociación Colombiana de Radiología.However, in today's ever-changing world with the discovery of novel techniques and technologies and new forms of practice and care models, there is an underlying concern about what this could mean for the future of the practice of radiology.

"This concern or premise is real, forcing us to think in a broader, more comprehensive way about the long term feasibility of the way radiology is practiced," he stated. "There are many in the medical community who agree that a certain number of assumptions may be considered unbreakable 'precepts' to guarantee, from the perspective of Hippocratic Ethics, the optimal practice of medicine for the benefit of the patient. These provisions include upholding the right for radiologists and diagnostics imaging professionals to practice independently within an interdisciplinary group."

At today's "ESR meets Colombia" plenary session, key figures from the country's radiology community will put forward their recommendations for other nations to consider the Colombian experience when looking at ways to maintain and raise the standard of quality in radiology.

The keynote session will focus on promoting a comprehensive strategy for navigating the radiology-centered regulatory laws. Prior to the enactment of Colombia's radiological law, the profession was marred by a number of deficiencies in the legal framework governing the practice of radiology, including the regulation of the operation of high-risk ionizing radiation, low-quality radiological practice by nonradiologist specialists, and the lack of trust of the general population and patients about the quality of radiology.

Use of PACS and voice recognition technology is increasing in Colombia.

Use of PACS and voice recognition technology is increasing in Colombia.According to the World Health Organization, countries with lower levels of social development are more susceptible to violations of patients' rights when it comes to the implementation of control instruments guaranteeing the quality of health services. As Restrepo explains, exhaustive and restrictive legislation becomes increasingly necessary in these types of situations, and, coupled with other social mechanisms such as effective monitoring and control systems, an appropriate balance between the regulated and executed can be obtained.

In Colombia, the subsequent implementation of a regulatory framework to govern the practice of radiology has imposed a number of essential restrictions on nonsuitable personnel, especially in the practice of ultrasound and general radiology, as well as the limitations imposed on other specialists practicing imaging, resulting in an acceptable level of service quality and patient safety.

Just as there are opportunities, there are risks to the ethics and quality of medical practice. The two main threats, self-reference and so-called perverse incentive, can be applicable in radiology and diagnostic imaging, which is why regulations are now in place in Colombia to guarantee the permanence, relevance, and independence of the attending radiologist.

An equally important issue concerns legal medical responsibility and the justice, malpractice, and civil or criminal consequences arising therein. Restrepo highlights suitability and independence as factors playing a key role in the burden of responsibility of the medical act. He believes interdisciplinary groups are the most expeditious formula to support the axiom that medicine is of means and not results.

Musculoskeletal imaging is an area of special expertise among Colombian radiologists.

Musculoskeletal imaging is an area of special expertise among Colombian radiologists."It is an inexact science in which the higher the number of experts to join in the process, the better the result and lower the load of individual responsibility," he continued. "The radiologist is essential and irreplaceable in this regard."

For over 70 years, the Asociación Colombiana de Radiología has shown its ability to adapt and evolve in line with the evolution of the specialty it represents. According to Dr. Frederico Lubinus, the current president of the association and a radiologist in the department of diagnostic imaging at Centro Medico Ardila Lulle, Bucaramanga, market needs and environmental pressures have forced today's radiologist to adapt to the multidisciplinary nature of the provision of healthcare, allowing for better use of resources with less morbidity and shorter hospital stays.

He thinks this change has been driven by the development of new diagnostic techniques that allow healthcare professionals to share large volumes of imaging data without the technological limitations in communications that occurred in the past. Furthermore, as the practice of radiology changes, so does the nature of professional associations; they move to adopt a more international outlook by aligning with other leading radiological societies across the globe.

"Being recognized as an influential partner in the world of radiology has meant that we are now able to participate in forums such as ECR to demonstrate our culture and achievements, and our peculiarities," said Lubinus.

Originally published in ECR Today on 6 March 2016.

Copyright © 2016 European Society of Radiology