What are the most common MRI biomarkers for breast cancer? Is breast MRI really diagnosing more false positives than mammography? What changes for preoperative breast MRI can be expected after the latest clinical trials? These are among the important unanswered questions in breast MRI, and they will be discussed at today's master class.

Dr. Francesco Sardanelli will talk about preoperative breast MRI in today’s master class.

Dr. Francesco Sardanelli will talk about preoperative breast MRI in today’s master class.MRI is the most sensitive and accurate test for ipsilateral staging of breast cancer and for screening of synchronous contralateral cancer, according to Dr. Francesco Sardanelli from the department of biomedical sciences for health at the University of Milan and director of radiology at the Research Hospital Policlinico San Donato in Milan.

"Importantly, several studies showed that those lesions detected with preoperative breast MRI are relevant (invasive, sometimes larger than the index lesion, biologically aggressive, etc.)," he said. "However, its use has not so far been associated with a better patient outcome, reducing recurrence or improving survival. Conversely, in many observational studies, preoperative breast MRI was associated with an increased rate of mastectomies."

Of four recent randomized controlled trials, two were in favor of preoperative breast MRI because there was a reduced reoperation rate, and two were against because there was no reduction in the reoperation rate. In this context, the mantra was "preoperative breast MRI increases mastectomy but does not improve patient outcome," explained Sardanelli, who is past president of the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI).

He thinks the Multicenter International Prospective Meta-Analysis (MIPA) trial will shed more light on the matter. Initial results of about 2,500 patients (with a target of 7,000) from 28 centers worldwide show 50% of patients had an MRI examination before surgery. Radiologists requested preoperative breast MRI the most, but surgeons were involved (alone or with another professional) in 40% of the cases. Also, the patients for whom a preoperative breast MRI is requested have a mastectomy already planned before MRI in about 20% of cases, and the increase in mastectomies after MRI is only 1%.

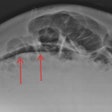

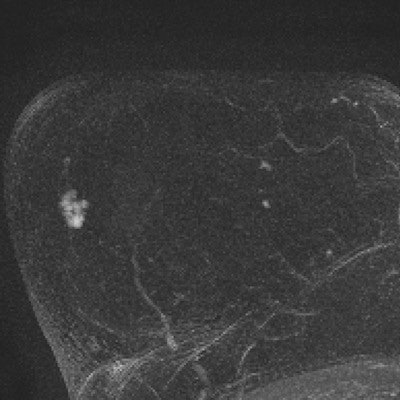

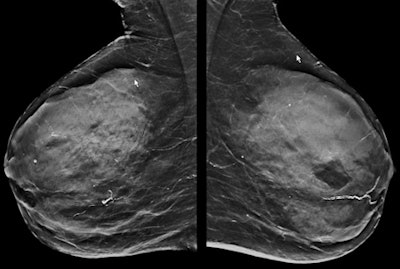

The dense mammogram (top) is negative, but an abbreviated breast MRI study (below) in the same patient is positive for small invasive cancer. In the first postcontrast subtracted image (Fast; bottom) of the slice and the corresponding maximum intensity projection image, the cancer can be clearly seen in the same patient. The patient underwent a MRI-guided biopsy, which confirmed presence of a grade 2 invasive cancer (no special type), 8 mm in longest diameter. All images courtesy of Dr. Christiane Kuhl.

The dense mammogram (top) is negative, but an abbreviated breast MRI study (below) in the same patient is positive for small invasive cancer. In the first postcontrast subtracted image (Fast; bottom) of the slice and the corresponding maximum intensity projection image, the cancer can be clearly seen in the same patient. The patient underwent a MRI-guided biopsy, which confirmed presence of a grade 2 invasive cancer (no special type), 8 mm in longest diameter. All images courtesy of Dr. Christiane Kuhl."Of those patients who have breast-conserving surgery, about 14% have more extensive surgery due to MRI but 12% to 13% have less extensive surgery," Sardanelli noted. "The reoperation rate is lower in those patients who had an MRI, but this has to be read in the light of the higher rate of mastectomies."

Sardanelli sees the MIPA trial as a way to combat the mantra against preoperative breast MRI and show the tool allows for a tailored breast conservative surgical treatment, i.e., precision breast cancer surgery.

"Clinical practice evolves not only based on guidelines, which frequently change very slowly, but also based on practice and experience," he said. "The condition for the use of preoperative breast MRI is a high-level cooperation between radiologists and surgeons."

In today’s master class Dr. Christiane K. Kuhl will raise the question of whether breast

In today’s master class Dr. Christiane K. Kuhl will raise the question of whether breastMRI increases the number of high-risk lesions.

Meanwhile, Dr. Christiane Kuhl, a professor of radiology and the director of the department of diagnostic and interventional radiology at the University of Aachen in Germany, urges ECR 2017 attendees to understand that not all false-positive diagnoses should be treated the same.

In breast imaging, a false-positive diagnosis is one in which malignancy is suspected but neither ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive cancer is found. However, a more useful definition would be to distinguish between "actionable" and "nonactionable" disease, she said.

Breast tissue produces nonproliferative changes, proliferative changes without atypia, and proliferative changes with atypia. Nonproliferative changes are associated with a 0.7- to 1.1-fold risk of breast cancer, while proliferative changes without atypia are associated with a 1.7- to 3.1-fold risk, and changes with atypia are associated with a 3.7- to 5.2-fold risk.

"Not all false positives are equal," she said. "The most important reason for mammography false positives is calcifications caused by regressive changes. It has nothing to do with cancer progression. As opposed to MRI with contrast enhancement, in cases with cell proliferation and atypia, this is the first step of carcinogenesis. This is something else. It has another connotation and implication for the patient. Calling it a 'false positive' is not appropriate."

In particular, certain kinds of lesions are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Atypical ductal hyperplasia is associated with a 40% increased risk of breast cancer, and lobular intraepithelial neoplasia and flat epithelial atypia are both associated with a 21% increased risk. These lesions are treated with intensified surveillance and possibly tamoxifen, so while they may be called false positives on MRI, they are not completely harmless, even though they are still categorized as benign, added Kuhl, who is a keen advocate of abbreviated breast MRI studies (see images above).

MRI depicts a biologic continuum, and many false positives are caused by the fact the continuum is divided into lesions that require treatment and lesions that do not, but MRI false positives are much closer to finding something that could lead to cancer than a false positive found on mammography, she continued.

"Cancer is not a black-and-white thing. There are shades of gray," Kuhl stated. "There is an entire process of breast cancer development, and with MRI we depict this process. We are able to see changes that have many features of cancer and that may develop into cancer."

With an increased understanding of the prognostic importance of tissue changes, "benign" is too simple a word, she pointed out. Benign could mean potential to progress to invasive cancer.

"It's time to rethink the nomenclature," she concluded.

Originally published in ECR Today on 5 March 2017.

Copyright © 2017 European Society of Radiology