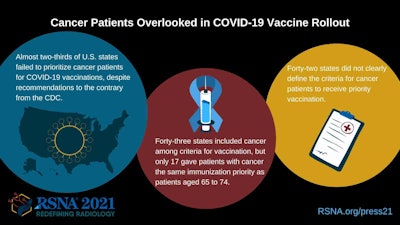

Most states winged it with poor results last spring when it came to prioritizing vulnerable cancer patients for COVID-19 vaccines, with guidance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) too broad to be useful, according to research presented December 2 at the RSNA 2021 annual meeting.

A group at Ohio State University in Columbus analyzed data on vaccinations in every state and found that more than 30 states did not follow CDC guidance to give equal early vaccination priority to cancer patients and patients aged 65 and older.

"With more infectious COVID-19 variants spurring continued, unchecked global spread, equitable prioritization of patients for booster shots may again be critical moving forward," said presenter Dr. Rahul Prasad, a radiation oncology resident at the university's Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The problem during the vaccine rollout last spring may lie in the group's secondary finding that just eight states appear to have taken steps to provide a precise definition for cancer diagnosis to meet the criteria for vaccination, the researchers found.

"Would a 55-year-old patient with breast cancer diagnosed 15 years ago and now in remission meet the criteria? What about a patient with very treatable, low-risk localized prostate cancer who hadn't yet received any immunosuppressive therapy?" Prasad asked.

In early 2021, the CDC recommended that states give equal vaccine priority to people over the age of 65 and patients aged 16 and older with high-risk conditions. This "prioritization scheme" resulted in an overwhelmingly large group of eligible people -- over 100 million -- and forced states to make their own prioritization decisions, Prasad said.

In this study, Prasad and colleagues searched the internet for each state's COVID-19 vaccination webpage and attempted to identify information about vaccinations for cancer patients.

The following are among the group's key findings:

- 43 states included cancer as a criteria for vaccination.

- Eight states precisely defined a qualifying cancer diagnosis.

- 17 states gave patients with cancer and patients over 65 years old the same priority.

- There was no relationship between per capita cancer prevalence and vaccine prioritization decisions.

Inclusion criteria for identifying high-risk patients, such as body mass index greater than 30, led to an overwhelmingly large number of patients and likely encouraged states to deemphasize the entire category to avoid crowding out elderly patients, Prasad suggested.

Image courtesy of the RSNA.

Image courtesy of the RSNA.Moreover, it doesn't help that patients themselves need to be significantly computer literate and navigate through multiple webpage subdomains to find detailed vaccination information, he added.

Ultimately, poor outcomes among cancer patients with COVID-19 infections are driven by a subset of patients: those with immunosuppression from active treatment, such as bone marrow transplant, chemotherapy, and large-field radiation therapy, as well as those with blood or metastatic cancers, Prasad said.

"Narrowing the definition of a cancer diagnosis meeting high-risk criteria could ensure that at least the highest-risk cancer patients receive priority vaccination," Prasad concluded.