Make no little plans.

Those were the words of planner and architect Daniel Burnham, who envisioned Chicago as a "Paris on the Prairie." He made his mark on the city, both through his "Burnham Plan," which was the largely realized plan for the parks, beaches, and museums that now dot the lakefront, and through his designs of several landmark buildings that remain vibrant 100 years after their construction.

Apart from bone-chilling winters, what sets Chicago apart from other North American cities is an abundance of architecture that is at once groundbreaking and fiercely independent. Along the way, the city has welcomed architects from around the world, and preserved a remarkable number of works by historic architects.

This means that someone armed with a good pair of walking shoes can view a veritable pantheon of great architectural works from past to present, all while remaining in downtown Chicago. Follow the walking tour below, picking up the route from your hotel where appropriate. Remember, Lake Michigan is always to the east.

Begin in the far southwest corner of downtown Chicago, at the corner of Wacker Drive and Adams Street.

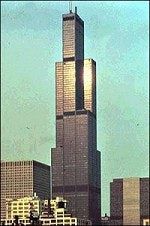

The Sears Tower (at right, 1974), 233 S. Wacker Drive, was designed by the firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. The1,454-foot-tall tower is known more for its height than for its architectural significance, but it is always worth seeing. After closing for six weeks to enhance security systems, the observation deck was reopened to the public on October 30.

Across the street is the whimsical, if not outright overwrought, 311 S. Wacker Drive building, whose wedding cake-like winter garden on top adds an extra touch to its grandiosity. The 959-foot-tall building was completed in 1989 and was designed by the New York City firm Kohn Pedersen Fox. The same firm designed one of the last "modern" office towers in Chicago before the early 1990s recession, the Chicago Title building (1992) at 161 N. Clark St.

The Sears and 311 S. Wacker buildings are a good starting point for this tour because they exemplify the city’s encouragement of bold ideas.

Head east (toward Lake Michigan) on Jackson Street, about three blocks. On your right will be Daniel Burnham’s Monadnock building at 53 W. Jackson Boulevard. While Burnham designed the north half of the building (completed in 1891, seen below), the south half was designed by the Chicago firm Holabird and Roche and finished in 1893.

Though a visionary, Burnham himself committed a major faux pas by using a now-obsolete method of construction involving load-bearing walls. Because load-bearing walls restrict the heights of buildings (the taller the structure, the thicker the base), the 16-story Monadnock stands as the nation’s tallest example of a structure with such walls. Its ascending walls have been rightly described as having graceful curves that resemble birds’ wings. Holabird and Roche’s south half of the building used steel-frame construction.

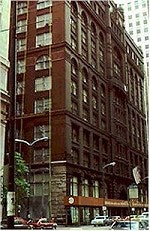

Walk west a block and a half to LaSalle Street, and turn right, going north to Burnham’s red, terra-cotta, Romanesque Rookery building, 209 S. LaSalle Street. If the lobby is open, check it out. The Rookery (below right), so named because it resembles the chess piece, was designed by Burnham and his partner, John Wellborn Root, in 1888. The lobby was "updated" in 1907 by Frank Lloyd Wright, making this the only example of Wright’s work in the downtown area.

If you’re able to access the lobby, check out its marble mezzanine staircase, which is adorned with gold leaf, as well as its cantilevered wrought iron stairwell. Catercorner to the Rookery is the 190 S. LaSalle Street building (1990), which is the only Chicago work designed by Philip Johnson, the celebrated, 95-year-old New York architect, and his partner, John Burgee. A grand postmodern building, 190 S. LaSalle’s design seems to pay its respects to the Rookery.

Continue north on LaSalle. Go one block to Monroe Street, and then turn right and walk two blocks east to the Inland Steel building (1958), which is considered Chicago’s first modern building. Skidmore architects Walter A. Netsch and Bruce Graham designed this shimmering stainless steel structure.

Now go back to LaSalle Street, turn right and walk north one more block to Madison Street, and turn left and go a half-block. On the left-hand side of the street is the sleek, gleaming 181 W. Madison Street tower (1990), one of the most celebrated "new" skyscrapers in Chicago. It was designed by Argentinian architect Cesar Pelli. The 50-story tower has Italian Luna Pearl granite on its exterior and four types of marble in its interior. Pelli also designed the world’s tallest buildings, the Petronas Towers in Malaysia.

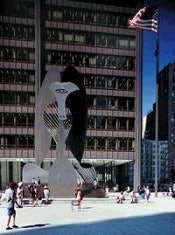

Now, walk east, past LaSalle Street, and then turn left on Clark Street. Going north, you’ll reach Daley Plaza, which is not particularly architecturally significant, but has an important landmark in its public square: artist Pablo Picasso’s untitled 50-foot-tall metal sculpture, which was erected in 1967 (below).

Walk another half-block north on Clark Street until you reach Randolph Street. Catercorner to the Daley Plaza to the northwest is the Helmut Jahn-designed James R. Thompson Center (1985), previously known as the State of Illinois building. The 16-story building, of mirrored glass and curved steel, is punctuated with blasts of orange and blue. It demonstrates Jahn’s vision for something different by placing granite-like touches at its extremities, then moving gradually away from granite toward glass and steel as one advances closer to the building’s interior.

Head north from the Thompson Center to Wacker Drive. Turn left and walk west four blocks to 333 W. Wacker Drive (1983), a green mirrored glass office tower designed by Kohn Pedersen and prominently featured in the movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. The curved building, which follows the contour of the street and the river, symbolizes the glitzy 1980s.

Do a 180º turn and walk back east on Wacker, past the more modest and stone-clad 31-story 225 W. Wacker Drive (1990) that Pedersen also designed. This building’s defining features are its four lantern-like towers. Keep walking east on Wacker. While you’re walking, gaze across the Chicago River at the massive Art Deco Merchandise Mart (1930), which at 4.2 million square feet is the largest commercial building in the world. The 25-story limestone-and-terra-cotta Mart was designed by the Chicago firm Graham Anderson Probst & White.

As you continue to walk east, go two more blocks until you reach the eye-catching, 50-story 77 W. Wacker Drive building (also known as the R.R. Donnelley building), which was designed by Spain’s Ricardo Bofill. The reflective glass building (1992) has a creamy white marble lobby, and an exterior of white granite pilasters and classical Doric columns and pediment. One local architect once described the tower as "Parthenon on a stick."

Continue north on Michigan Avenue across the bridge. On your right is Tribune Tower (1922), the 36-story neo-Gothic building at 435 N. Michigan Avenue. Still the home of the Chicago Tribune newspaper, the tower was designed by Raymond Hood and John Meade Howells. On your left is the white, terra-cotta clocktower-topped Wrigley Building (1924, below right), 400-410 N. Michigan Avenue, also designed by the Anderson firm.

Proceed north on Michigan Avenue about a half-mile to the John Hancock Center (1969), the 100-story skyscraper that is the work of Skidmore architects. Located in the northeast corner of downtown Chicago, the 1,127-foot-tall Hancock provides the perfect steel complement to the Sears Tower. Either take a ride up to its observatory or have a drink at the Signature Room on its 96th floor.

When you’re through, proceed east on Delaware Street (along the north side of the Hancock building) about four blocks to Lake Shore Drive. Here you’ll see the two Ludwig Mies van der Rohe-designed 26-story condominium buildings at 860 and 880 N. Lake Shore Drive (1948-1951). Van der Rohe once referred to his style as "skin and bones architecture," and this set embodies van der Rohe’s desire for minimal elegance. The influence of these black steel-and-glass buildings was far-reaching because they served as prototypes for an entire generation of office and residential buildings.

Finally, complete your survey of Chicago’s architectural luminaries by going south two blocks on Lake Shore and turning right on Chicago Avenue, heading west to the Museum of Contemporary Art (1996), 220 E. Chicago Avenue. This square, modernist glass-and-stone building, designed by German architect Josef Kleihues, is set on a base of Indiana limestone and features aluminum panels fastened with visible steel pins.

There has been some debate over Kleihues’ design. Art dealer Richard Feigen charged that the museum’s new building should have rivaled Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim building in Bilbao, Spain in terms of architectural significance (Tales from the Art Crypt: The Painters, the Museums, the Curators, the Collectors, the Auctions, the Art, Knopf, 2000). Kleihues has paid homage to van der Rohe in his design, as well as to Chicago’s strong beaux arts tradition. Drop in for a visit and check out its minimalist interior.

By Bob Goldsborough

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

November 14, 2001

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com