Radiologists may believe that chronic pulmonary embolism is harder to diagnose than the acute kind. But the task is as simple and straightforward as acute PE if one knows what to look for, according to Dr. Martine Rémy-Jardin, from the University of Lille in France.

The thoracic and cardiovascular imaging expert, well known for knowing what to look for, shared her experience in detecting chronic PE at the 2004 International Congress of Radiology (ICR) in Montreal.

The literature, though much of it is old and based on V/Q scintigraphy studies rather than CT, clearly shows that most acute PE resolves itself completely over time, even when treatment is inadequate, said Rémy-Jardin, a professor of radiology at the University of Lille in France.

The same studies also show that CT, even thick-slab acquisitions acquired on early CT scanners, offers superior diagnostic capabilities compared to pulmonary angiography, an invasive x-ray test that can exacerbate the delicate state of many PE patients. A study comparing CT with MRA also concluded that CT was the better exam, particularly in the peripheral circulation, due to CT's ability to depict the thrombotic walls directly, she said.

"Clearly if we add thin collimation, plus the additional reformations, we can do better with CT angiography," Rémy-Jardin said.

Signs of chronic PE

Chronic PE arises from a small percentage of acute PE cases in which the emboli do not resolve, but instead organize and incorporate themselves into vessel walls within the pulmonary arterial tree, progressing to chronic PE.

The affected arteries are often seen to retract, recanalize, and over time become calcified. The impeded blood flow can lead to progressive pulmonary hypertension, which itself is a sign that emboli from a past episode of acute PE may have not resolved, Rémy-Jardin said. In such cases, pulmonary thromboendarterectomy can be very helpful for restoring normal blood flow, and relieving the excess pressure underlying the hypertension.

Setting her sights on a thoracic CT slide, Rémy-Jardin pointed out multiple emboli that had lodged in the right pulmonary arteries of one patient -- persisting, she said, more than eight years after a massive episode of acute PE. The image also demonstrated retraction of arteries at the site of the original emboli.

"This unfavorable outcome occurs, hopefully, in a lower percentage of patients (compared to acute PE)," Rémy-Jardin said, "but we don't know exactly when it is going to develop, and there are several question marks still present in the literature, and in our general understanding of chronic thromboembolic disease."

In any case, CT angiography can produce a definitive diagnosis, she said. In a study of patients who had suffered from "massive" acute PE, Rémy-Jardin and colleagues found that 13% of the cohort had evidence of chronic PE. More troubling was that the affected patients had neither clinical symptoms nor pulmonary hypertension (Radiology, April 1997, Vol. 203:1, pp. 173-180).

"These findings help us understand why this disease has a very insidious development, and why it's difficult to diagnose at an early stage," she said. The literature shows that PE can result either from unresolved massive acute PE, or from a lifelong predisposition, leading to recurrent episodes of acute events that can result in chronic obstruction of the pulmonary arteries.

Keys to diagnosis

The radiologist's search for chronic PE can be boiled down to four words, Rémy-Jardin said. "The four key words are organization, calcification, recanalization -- and a very important CT finding, which is retraction of the chronically obstructed pulmonary artery," she said.

Organization: The organization of embolic material can be detected by the presence of partial or complete filling defects, Rémy-Jardin said. Unfortunately, the age of the thrombi cannot be determined by the presence of filling defects alone, so additional clues are needed to distinguish it from acute PE.

|

| Organization of emblic material. All images courtesy of Dr. Martine Rémy-Jardin. |

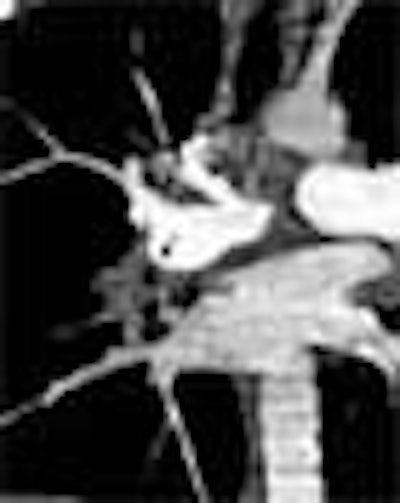

Recanalization: Within the artery, the radiologist can readily detect the recanalization channels, filled with blood that has been opacified by the contrast material. The channels tend to be located very near the areas of nonperfusion due to chronic obstruction, and the presence of focal stenoses can be indicative of recanalization, she said. In addition to transverse sections, additional reformations in the coronal and sagittal planes can often be helpful in delineating the morphology of the channels. "When the stenoses are in the plane of reformation, they are not easily detected in transverse sections," Rémy-Jardin said.

|

| Recanalization of embolic material. |

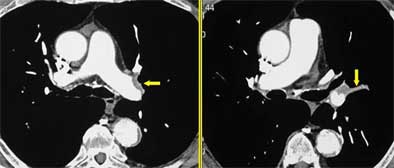

Retraction: Evidence of arterial retraction is the most telling sign that the PE findings are chronic rather than acute. Retraction can be ascertained by comparing the diameter of the suspect arteries with the contralateral vessels. Retraction is the most significant finding in chronic PE, and the diagnosis cannot be contemplated in its absence, she said.

|

| Retraction of embolic material. |

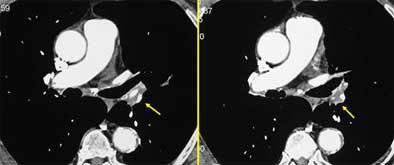

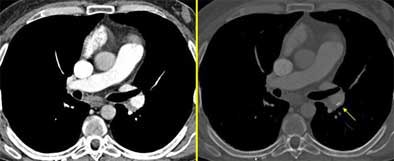

Calcification: Calcification of emboli is commonly seen in chronic PE. However, it can occur in a number of disorders, she said.

|

| Calcification of embolic material. Maximum intensity projections (MIPS, above right, W: 1900 HU, C: 370 HU) are often helpful in distinguishing hard-to-find calcifications. |

More clues

Certainly diagnosing chronic PE on the basis of CT images alone is a difficult undertaking, she said; the patient's clinical information can offer important details in difficult cases.

Faced with equivocal findings, a re-examination of the bronchial arteries in the mediastinum can also be helpful -- using the standard thin-section CTA protocol and high concentration of contrast material, Rémy-Jardin said.

The presence of dilated arteries is another sign of chronic PE. Acute PE is seen only rarely in combination with dilatation, but more commonly in chronic PE. Thus, patients with a higher relative percentage of dilated arteries are likelier to have chronic PE.

"Additional arteries around the thorax can also develop as a consequence of this chronic obstruction of the pulmonary circulation," she said. "Here is an example of this dilatation of the internal mammary artery, and here the dilatation of the inferior phrenic artery, also participating in this collateral supply. When we have a patient with pulmonary hypertension, and when we don't know the exact etiology of this hypertension, it's interesting to have a look at these arteries."

Transverse sections are often sufficient to find the four key signs of chronic PE and render the diagnosis, but additional reformations are often needed in clinical practice, to better delineate the morphology, she said.

Pointing to another slide, Rémy-Jardin said that one patient had pulmonary hypertension, but lacked any of the key signs of chronic PE, except in a very small region characterized by low attenuation.

"Is it endo- or perivascular? We can answer the question by means of these oblique coronal reformations, where you can see this endoluminal filling defect extending up into the right upper lobar pulmonary arteries," she said. "Here you have a very thin filling defect located at the periphery of the pulmonary arteries -- it's easier to look at them on these images compared to transverse sections."

Maximum intensity projections (MIPs) can also be helpful for enhancing hard-to-see calcifications, especially when they are located in the periphery of the pulmonary vasculature. MIPs can help determine whether the calcifications are really connected to pulmonary vessels, she said.

The lung parenchyma also yields clues to the diagnosis of chronic PE, particularly in areas of mosaic perfusion due to areas of high attenuation and dilated vessels. There are two causes for this appearance, she said. First, areas where blood flow is obstructed and redistributed contribute to the appearance of a ground-glass attenuation pattern. Second, she said, areas of hyperattenuation can result from dilatation of the bronchial arteries.

Reformatting images

In addition to the 2D reformations that are the workhorses of PE diagnosis, newer workstations can generate 3D volume-rendered reconstructions, which can produce, among other things, images that look very much like traditional angiography.

"Volume-rendered images can be helpful," she said. "We can look at them with different viewing angles. We can see areas of stenosis that can be missed on the conventional digital angiogram, because even if we have several orthogonal views, we cannot detect all these vascular abnormalities from the (2D) images."

What the surgeon needs

Surgeons perform pulmonary thromboendarterectomy to reduce the extent of pulmonary vascular obstruction, which in turn can relieve excess pulmonary artery pressure and improve cardiac function, Rémy-Jardin said.

The radiologist's principal goal is to give the surgeon the essential morphologic information needed for presurgical planning. The surgeon needs to know the location of the first part of the central obstruction. He would like to see the clots at the segmental level, but ideally starting at the lobar level. MDCT's ability to depict clots down to the subsegmental emboli makes it the technique of choice for surgeons performing this delicate operation, which is often performed only in specialized centers, Rémy-Jardin said.

Yet despite CT's demonstrated superiority, many surgeons persist in ordering pulmonary angiography studies, she said, reading from a 2004 study that "pulmonary angiography is essential in establishing the presence of chronic thromboembolic obstruction, in defining its extent and proximal extension ... and excluding competing diagnostic possibilities."

"When chronic PE is present, I hope to have convinced you that it can be detected on CTA," she said. "But much work has to be done by radiologists in order to convince the surgeons that this is a very interesting tool to evaluate very often fragile patients."

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

October 15, 2004

Related Reading

CT for PE: Best test gets better, September 10, 2004

MDCT drives important changes in U.K. healthcare, August 10, 2004

Combined test strategy safely detects pulmonary embolism in outpatients, March 11. 2004

MDCT pulmonary angiogram rules out PE for months, March 22, 2004

Volumetric capnography points to pulmonary embolism, March 17, 2004

CT assessment of pulmonary embolus predicts prognosis, March 16, 2004

Copyright © 2004 AuntMinnie.com