In a face-off that's making waves on both sides of the Pacific, a board-certified gastroenterologist outperformed a board-certified radiologist in detecting polyps with virtual colonoscopy (VC or CT colonography [CTC]), researchers report.

Of course the small, two-reader study presented at the recent Digestive Disease Week (DDW) meeting in San Diego isn't earth-shatteringly significant in the grand scheme of things. And the results do not prove that gastroenterologists make better VC readers than radiologists. However, the multicenter study from sites in Japan and the U.S. does suggest that the rare gastroenterologist who might be interested in performing virtual colonoscopy can do so on par with his colleagues in imaging.

The prospective study compared the two professionals' reading performance in a group of patients who underwent two kinds of bowel preparation. Results showed that the gastroenterologist detected a few more medium-sized polyps than the radiologist did -- while the radiologist may have had a slightly easier time distinguishing polyps from residual fecal material. Both readers achieved 100% sensitivity for polyps 10 mm and larger.

The research was led by gastroenterologist Dr. Koichi Nagata, currently at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, along with his MGH colleague Dr. Hiro Yoshida. The Japanese research team included radiologist Dr. Tomohiko Okawa and Akihiro Honma from Tokyo-West Tokushukai Hospital in Tokyo and gastroenterologists Dr. Shungo Endo and Dr. Shin-ei Kudo from Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital in Yokohama.

Japanese gastroenterologists are interested in CTC in part because they're authorized to perform it, Yoshida told AuntMinnie.com in an interview. "In Japan a GI can play a main role in reading VC as well as colonoscopy -- so it's a place where actual same-day exams could take place."

Unfortunately, the country lags behind the U.S. in terms of formalized training. Both study readers were self-taught, with the general radiologist reading about 100 CTC cases and the gastroenterologist reading about 350 CTC cases, according to Yoshida.

Moreover, CTC is "not officially approved" for colorectal cancer screening and is therefore largely restricted to research settings in Japan, Yoshida said, though it is becoming "more popular for secondary screening of high-risk patients," such as those with a positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT), as a replacement exam for barium enema. And VC is commonly used presurgically in patients with colon cancer and other findings requiring intervention, he said.

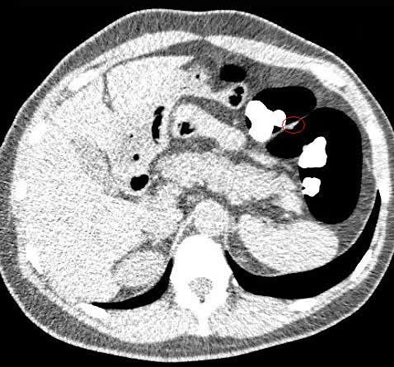

All CTC exams in the study were performed on a 64-slice CT scanner (Aquilion 64, Toshiba Medical Systems, Tokyo) in a cohort of subjects who underwent one of two types of bowel preparation before scanning, followed by optical colonoscopy.

The researchers examined 100 subjects at increased risk of colon cancer and polyps, as indicated by a positive FOBT or bright red blood per rectum. Same-day optical colonoscopy performed after VC in all patients served as a reference standard.

Of the 100 cases, 40 were selected randomly for the study analysis, Yoshida said, with half of those randomly allocated to a minimal bowel preparation regimen (n = 20) and half receiving a laxative prep (n = 20).

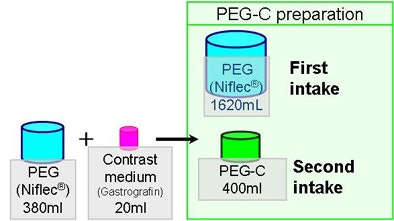

The same-day preparation group consumed 2-L polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution in the morning, with CT scans acquired in the afternoon. The prepped patients also received 20 mL of water-soluble sodium/meglumine-diatrizoate contrast medium (Gastrografin, Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ) for fecal tagging, without dietary restrictions.

"The amount of PEG is a little smaller than [the dose] used here in the states," Yoshida said.

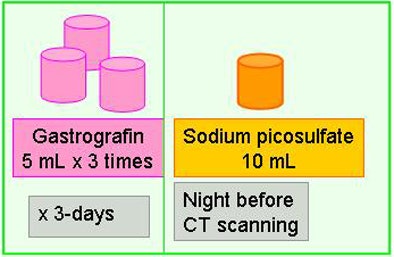

The reduced preparation group consumed Gastrografin at each low-fiber meal for three days prior to CT scanning. These patients received a total of 45 mL of contrast medium during the three days, in addition to 10 mL of sodium picosulfate the night before the scan.

Colonic insufflation was performed using manual room air, Yoshida said, noting that automated CO² insufflation is not yet approved for use in Japan. Overall, distension proved to be adequate, he said.

The biggest challenge was the residual fluid seen in some PEG-prepped cases owing to a lack of electronic cleansing software, especially when untagged feces were present, Yoshida said. For this reason, all studies were read using a primary 2D approach, with 3D confirmation of findings performed "whenever possible," he said.

Optical colonoscopy was performed by experienced gastroenterologists after VC in all cases; the VC readers were blinded to colonoscopy results.

The CT datasets were postprocessed using commercially available software (Ziostation system 510, Ziosoft, Redwood City, CA).

Polyp locations were assigned to one of six colonic segments: rectum, sigmoid colon, descending colon, transverse colon, ascending colon, and cecum. Locations other than the cecum were further noted as proximal, mid, or distal within each segment. Polyp size was measured on 2D images using an electronic ruler, and the final diagnosis was made by consensus of the readers.

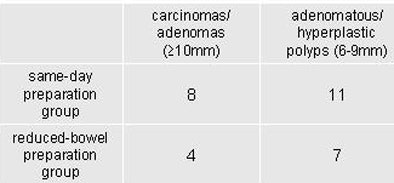

In the 20 patients who underwent same-day bowel preparation, optical colonoscopy found eight carcinomas or adenomas 10 mm or larger and 11 adenomatous or hyperplastic polyps ranging from 6-9 mm in size.

In the 20 patients who underwent a reduced bowel preparation, researchers found four carcinomas or adenomas 10 mm or larger and seven adenomatous or hyperplastic polyps 6-9 mm in size, all confirmed by optical colonoscopy.

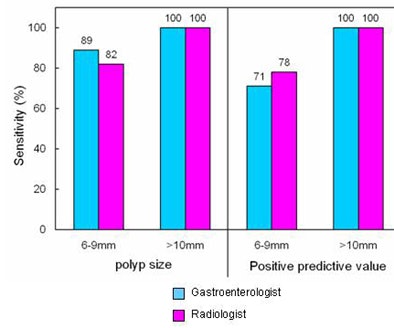

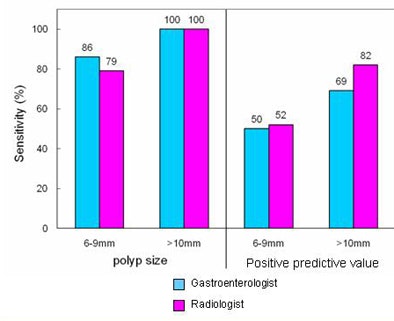

In the same-day preparation group, per-polyp sensitivities of the gastroenterologist and the radiologist were 91% and 73%, respectively, for polyps 6-9 mm. Per-polyp sensitivities in the reduced bowel preparation group were 86% and 86%, respectively, for polyps 6-9 mm. In both preparation regimens, sensitivities of the two readers were 100% for polyps 10 mm or larger, Nagata and his colleagues reported.

In the same-day preparation group, false-positive findings per patient for the gastroenterologist and the radiologist were 0.15 and 0.1, respectively, while those in the reduced bowel preparation group were 0.3 and 0.2, respectively.

VC with reduced prep was less sensitive for medium-sized polyps and generated more false positives than the same-day preparation, Yoshida said.

While both the gastroenterologist and radiologist were able to detect polyps 10 mm or larger at 100% sensitivity in both preparations, the gastroenterologist found more medium-size polyps, the group concluded. Overall, there was no statistically significant difference between the sensitivities of the gastroenterologist and the radiologist in the detection of polyps. Thus, the gastroenterologists with CT colonography training could read CT colonography with clinically acceptable high accuracy.

"With the minimal prep laxative there were more difficult cases to differentiate between stool and polyps because some [stool was] not really tagged, so that's going to lower the specificity to some extent," Yoshida said. "In terms of differentiating between the two readers, there was not much difference between the gastroenterologist and the radiologist."

Yoshida speculated that the gastroenterologist might have performed a little better in detecting medium-sized polyps because he had more reading experience (350 cases) compared to the radiologist's 100 cases.

"The lesson is, it doesn't matter who you are," Yoshida said. "Like many other studies, it shows that the amount of training may be more important than whether [the reader] is a gastroenterologist or a radiologist."

Steep learning curve

The learning curve for nonradiologists is particularly steep, cautioned Dr. Abraham Dachman, professor of radiology at the University of Chicago. In the December 2007/January 2008 AGA Perspectives, he wrote that nonradiologists trained in CTC interpretation tend to show wider variability in performance compared to their radiologist counterparts.

"Several gastroenterologists I have trained have confided that they now understand why CTC is best left to radiologists, due to the complex problem-solving skills needed to become a facile interpreter of CTC exams," he wrote. "Furthermore, significant extracolonic findings requiring further workup occur in 4% to 12% of screening CTC exams."

Along with skills the reader will need to hone for detecting polyps and operating a workstation, the CT technologist must master additional skills when the exam is not performed under the control of a radiologist, the article continued.

"Technologists acquiring the data for CTC without the direct supervision of a radiologist must learn to recognize excessive retained colonic fluid and know when to add additional decubitus views or employ additional maneuvers to further distend the colon," Dachman wrote. "Nonradiologists are less likely to possess or be willing to learn and teach these skills. The weakest link in the chain of polyp detection in CTC is often the poor quality of colon distension. Even the most expert reader will not consistently provide accurate readings if the exam quality is not carefully controlled."

In an interview with AuntMinnie.com, Dachman said that "extracolonic findings are important, split billing [for radiologist overreads] is a problem," and nonradiologists will have to "meet the same quality metrics" as radiologist readers. Nevertheless, he said, those who are truly motivated by a desire to optimize patient care and who are willing to spend the substantial time necessary to learn VC can become expert readers.

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

June 6, 2008

Related Reading

Learning curve: VC ramps up spring training, March 7, 2008

ACR plans leading role in virtual colonoscopy education, August 13, 2007

Careful reading boosts virtual colonoscopy results, July 26, 2007

Gastroenterologists plan to perform VC, January 28, 2007

VC experts have an edge over less experienced readers, March 8, 2005

Copyright © 2008 AuntMinnie.com