A patient whose cancer treatment is delayed by even one month can face a mortality risk of up to 13% higher, a Canadian and U.K. study has found. The investigation, published online by BMJ on 4 November, was triggered by concerns about delays to cancer diagnosis and therapy during the pandemic.

"There is a growing realization that particularly national or regional lockdowns, come at a cost to wider health and welfare of societies," stated the authors, led by Dr. Timothy Hanna, PhD, clinician-scientist at Queen's University in Kingston, Canada. "We now need to count the previously invisible cost of COVID-19 on people with cancer."

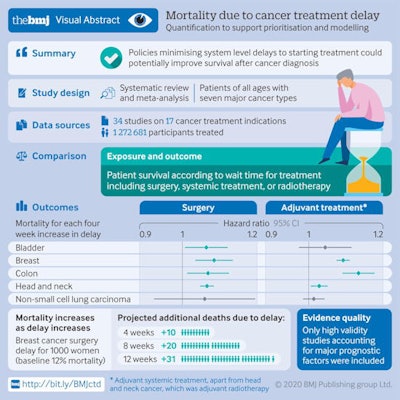

Previous meta-analyses and high validity studies have shown that delays in cancer treatment can have adverse consequences on outcome or local control, but the researchers were motivated by a lack of standardized estimates of this effect for most treatment indications. They considered seven major cancer types and three treatments (surgery, systematic treatments such as chemotherapy, and radiotherapy) with data showing that a four-week delay is associated with increased mortality and longer delays with further mortality.

"These results are sobering and suggest that the survival gained by minimizing the time to initiation of treatment is of similar (and perhaps greater) magnitude of benefit as that seen with some novel therapeutic agents," they noted.

Graphic shows the main results of the study. All images courtesy of Hanna et al. BMJ open access

Graphic shows the main results of the study. All images courtesy of Hanna et al. BMJ open accessThe results do not consider the impact of treatment delay on local control rates, functional outcomes (e.g., continence, swallowing), complications from more extensive treatments because of progression during delays, quality of life, or the greater economic burden because of higher direct care costs and productivity losses due to premature mortality and morbidity. Therefore, the impact of treatment delay is probably far greater for patients and society than that reflected in the results, according to the authors.

The authors suggested that in light of these results, policies focused on minimizing system-level delays in cancer treatment initiation could improve population-level survival outcomes.

The impact of treatment delay on outcomes has come into focus during the COVID-19 pandemic because many countries have experienced deferral of elective cancer surgery and radiotherapy as well as reductions in the use of systemic therapies, while health systems have directed resources toward preparing for the crisis. The researchers therefore aimed to precisely quantify the association of cancer treatment delay and mortality for each four-week increase in delay to inform cancer treatment pathways.

The team carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of relevant studies published in Medline from 1 January 2000 to 10 April 2020, and it included 34 studies for 17 indications (n = 1,272,681 patients).

These studies had data on surgical interventions, systemic therapy (such as chemotherapy), or radiotherapy for seven forms of cancer: bladder, breast, colon, rectum, lung, cervix, and head and neck.

Drastic results

Their main outcome measure was the risk to overall survival per four-week delay for each indication and delays were measured from diagnosis to first treatment, or from the completion of one treatment to the start of the next. The association between delay and increased mortality was significant for 13 of the 17 indications. Across all three treatment approaches, a treatment delay of four weeks was associated with an increase in the risk of death.

For surgery, the researchers found a 6% to 8% increase in the risk of death for every four-week treatment delay, while this was even greater for some radiotherapy and systemic indications, with a 9% and 13% increased risk of death for definitive head and neck radiotherapy and adjuvant (follow-up) systemic treatment for colorectal cancer, respectively.

In addition, the researchers calculated that delays of up to eight weeks and 12 weeks further increased the risk of death and used the example of an eight-week delay in breast cancer surgery that would increase the risk of death by 17%, as well as a 12-week delay that would increase the risk by 26%.

The authors revealed that a surgical delay of 12 weeks for all patients with breast cancer for a year would lead to 1,400 excess deaths in the U.K., 6,100 in the U.S., 700 in Canada, and 500 in Australia, assuming surgery was the first treatment in 83% of cases, and mortality without delay was 12%.

The team also pointed to how their results could help to directly shape policy, citing how the U.K.'s National Health Service had used an algorithm to prioritize surgery at the beginning of the pandemic: A number of conditions had been considered safe to be delayed by 10 to 12 weeks with no predicted impact on outcome, including all colorectal surgery, while the study found that increasing the wait to surgery from six weeks to 12 weeks would increase the risk of death in this setting by 9%.

In terms of limitations, the study was based on data from observational research that cannot perfectly establish cause, and it is possible that patients with longer treatment delays were destined to have inferior outcomes because of having multiple illnesses or treatment morbidity, the authors noted. However, the analysis was based on a large amount of data that included high-quality studies with high validity, the authors wrote.