With intensive remedial work, the brains of dyslexic children can be "rewired" to function more like those of normal readers, researchers report. Functional MRI scans are showing child development experts exactly how this rewiring process works.

In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, investigators from Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, used standardized educational testing and brain imaging to investigate the efficacy of a commercial computer program for training dyslexic children to read. This is the first study of its kind, according to lead researcher Elise Temple, Ph.D., assistant professor of human development.

"From a scientific perspective, the most important implication to this research is simply that it can be done," Temple explained. "Previously we did not know if the (imaging) techniques would be sensitive enough to detect brain plasticity of this sort. This study marks the beginning of a whole area of research that looks at the effects of training and education on the brains of children."

fMRI was critical to this work because it is noninvasive, Temple added. "Other methods...like PET require the injection of radioactive substances and so are not allowed with children. The advent of fMRI made this study possible."

The investigators used a commercial computer program (Fast ForWord Language, Scientific Learning Corporation, Oakland, CA), to train the children to process the changing sounds inside of words (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, March 4, 2003, Vol. 100:5, pp. 2860-2865).

"For example, a dyslexic child may be unable to distinguish between letters that rhyme, like B and D," wrote co-investigator Paula Tallal, Ph.D, professor of neuroscience at Rutgers University in Newark, NJ. "If you hear the sound 'ba' in 'butter' and 'da' in 'Doug,' the only way we know the difference is in the first 40 milliseconds of the onset of those sounds. The ability to extract sounds out of words is what is called phonological awareness. Words can be broken into sounds, and these sounds have to be mentally connected with letters. Although the process might seem intuitive, it is actually a learned skill."

Tallal also serves as the co-director of Rutgers-Newark Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience.

The subjects used the computer program at school for 100 minutes a day, five days a week. The program consisted of seven exercises adapted as computer games. "Each child worked at his or her own level," Tallal said. "The goal was to have the children process sounds correctly in words and sentences of increasing length and grammatical complexity."

The study included 20 dyslexic children aged 8-12 years. They underwent fMRI scans at the Lucas Center for Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy at Stanford University in Stanford, CA, before and after participating in the eight-week training program. A control group of 12 children with normal reading skills also underwent scans, but did not use the Fast ForWord Language training.

The children were scanned on a 3-tesla MR unit (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI). The researchers identified changes in blood oxygenation in various brain regions, indicating changes in neuronal activity over the eight-week course of the study.

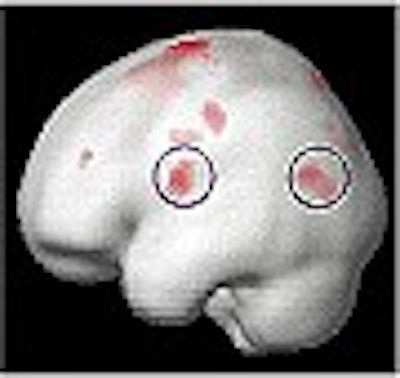

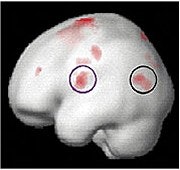

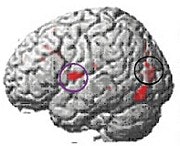

At the beginning of the study, MRI scans of the 20 dyslexic subjects contrasted sharply with those of the 12 normal readers in the control group; the dyslexic subjects' scans showed a lack of activity in the language-critical temporal regions of the brain.

|

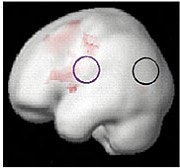

Brain function in child with no reading disability (top); brain function in child with developmental dyslexia (middle); children with dyslexia show increased brain function after training (below). Images courtesy of Elise Temple, Ph.D.

|

At the end of the eighth week, the investigators found that, among the dyslectic subjects, areas of the brain critical to reading skills had become activated, and had begun to function more normally. Other regions of the brain also showed activity on the MRI scans, suggesting a gradual compensatory process that would help the dyslexic subjects learn to read more fluently.

"This fMRI study demonstrates that a training program explicitly designed to mimic the learning routines used in neuroplasticity studies with animals results in significant amelioration of aberrant metabolic activity in dyslexic subjects in (brain) areas important for phonological processing," Tallal wrote.

Results such as these can go a long way to backing up educational interventional programs, Tallal concluded.

"In light of President Bush's legislation, 'No Child Left Behind,' which mandates that only scientifically validated applications be used for intervening with children, this program has the potential to help address the crisis we are facing in the large number of children failing to meet (educational) standards," she wrote.

By Bruce SylvesterAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

April 25, 2003

Related Reading

Child neurologists set guidelines for tests of global developmental delay, October 29, 2002

Brain scans offer clues to language development, May 27, 2002

Dyslexia due to neurocognitive deficit varies by language, May 17, 2001

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com