Conventional wisdom holds that people who are born blind find ways of compensating for the missing sense, such as through better ability to remember verbal information. Investigators from Israel used functional MRI (fMRI) to show that strong verbal memory in the blind is more than just an anecdotal belief -- there is an anatomical basis for the phenomenon.

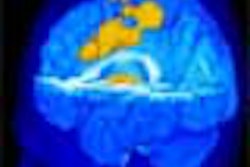

Congenitally blind people recruit their occipital cortex, and specifically the primary visual cortex (V1), for the task. The study was published in the latest issue of Nature Neuroscience (July 2003, Vol. 6:7, pp.758-766).

What’s more, Dr. Ehud Zohary and colleagues found that the magnitude of the activity in the region during verbal memory tasks is positively correlated with the individual’s ability. Zohary is from the neurobiology department at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. His co-authors are from the Wohl Institute for Advanced Imaging in Tel-Aviv and the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot.

The group used a whole-body, 1.5-tesla Signa Horizon LX scanner (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) to image the occipital cortex of 10 blind and seven sighted subjects, while they performed six different memory and tactile tasks.

The key test involved language processing without sensory input; specifically, the ability to recall a list of abstract words, chosen to have no visual associations, from long-term memory (the list was learned a week before the scan).

During that test, Zohary and colleagues found the blind subjects showed activation near the left calcarine fissure, the normal location of the primary visual cortex. The sighted subjects showed no activation in the region.

The same region was active in the blind subjects (but not the sighted ones) during a verb-generation test, in which the subjects were asked to retrieve a verb corresponding to a heard noun (such as "read" for "book").

There also appears to be a topographical preference: the anterior regions of the occipital cortex were more active during tactile Braille reading, while the posterior regions were more active during the verbal-memory and verb-generation tasks.

The results support the idea that blind people have better verbal memories than sighted people, but not through a "drastic reshuffling of the memory circuitry," the authors concluded. Instead, "the blind seem to have an additional memory-related region, located in the occipital cortex."

It’s possible that blind people -- forced to rely more heavily on verbal memory than the sighted -- develop a "practice-induced reorganization" of the visual cortex, which is deprived of its usual function and is thus available.

An additional piece of evidence could be derived by creating virtual transient lesions (using transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS) in the occipital cortex of blind people during memory tasks. If the region is as essential to memory ability, as this study suggests, the TMS should degrade performance, Zohary told AuntMinnie.com.

Commenting on the study, Dr. Christian Buechel of the Center for Imaging Neuroscience at the University of Hamburg in Germany called the results "astonishing."

In an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com, Buechel said the study demonstrates that the functional structure of the occipital cortex is "not carved in stone." Instead, the normal functional structure is a result of development under constraints, specifically, visual input.

But when that input is missing, he said, it appears that different functions can arise.

The findings also appear to turn the hierarchy of the region on its head, he said: In sighted people, the V1 region is an early-stage interpreter of visual input, while in the blind it is used for memory, usually a higher-level task.

By Michael SmithAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

July 24, 2003

Related Reading

Amnesiacs retain some memories, according to MR studies, April 4, 2003

fMRI reveals secrets of better memory, January 13, 2003

FDG-PET spies early decline in forgetful folks, October 22, 2002

Women, men use different parts of brain to remember, July 24, 2002

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com