With the rise of sport as big business and the emergence of the weekend warrior, sports injuries have become a booming healthcare specialty unto themselves. According to The Merck Manual, more than 10 million of them are treated in the U.S. every year. The primary cause? Overuse.

Overuse injuries often require more finesse to detect than trauma injuries such as fractures. These same methods, though, can also be used to stop minor injuries from becoming career-ending ones. Here’s how basketball players, runners, cyclists, and wheelchair racers are taking advantage of state-of-the-art imaging to predict, prevent, and diagnose overuse injuries.

Training and equipment issues

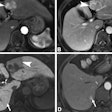

Elite athletes risk serious overuse injuries that can go undiagnosed. Dr. Nancy Major, associate professor of musculoskeletal imaging and orthopedic surgery at Duke University in Durham, NC, cited long-distance runners as an example.

"All of our (runners) were training for ultramarathons -- 50K, 50-mile, and 100-mile races. Three had findings on physical exam of regular lumbar spine disease, and it was attributed to having sciatica," she said.

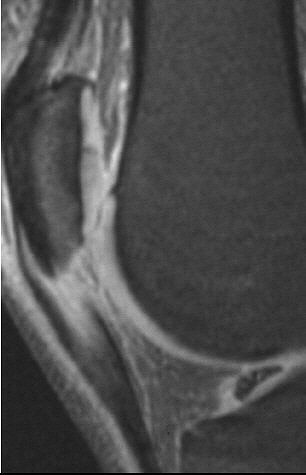

|

| Sagittal MR image of jumper's knee depicting an abnormal signal and the size of the patella tendon in a basketball player. Image courtesy of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC. |

However, Major continued, "when the MR was done in one person, a sacral stress fracture was found. The others had MR also, and they too had sacral stress fractures. All along they’re thinking they have disc disease, and so it’s probably occurring much more commonly than we think. Making the diagnosis is key, and it’s a very easy diagnosis to make with MR."

Cycling is another sport whose athletes sustain overuse injuries that are tricky to diagnose. Even though running involves impact and cycling does not, athletes in both sports require close scrutiny for subtle clues to serious problems.

"Running is very different from bicycling, but the similarities between the issues of overuse are pretty close," said physical therapist Erik Moen, director of health services for Carmichael Training Systems in Colorado Springs, CO. CTS is the coaching service of Chris Carmichael, who trained five-time Tour de France champion Lance Armstrong.

"Overuse injuries often result from a combination of things: improper training, musculoskeletal challenges, and improper equipment fit. Things such as leg-length discrepancy play a part, and bony or muscular asymmetries," Moen said. "Those factors need to be considered when diagnosing or working with an overuse injury for bicycling."

|

| MRI of sacrum in an ultramarathoner showing abnormal signal of a stress fracture. Image courtesy of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC. |

Dr. Errol Toran of Excel Chiropractic at Medical on 42nd Street in New York City often treats such injuries. He describes a common pelvic distortion that can compromise athletic performance.

"Two ilia are completely counter-rotated -- one rotates back, one rotates forward. The result of the ilium that rotates posteriorly is that the sacrum tends to fall to that side, (and) the spinal column’s going to fall with gravity to the same side. You can’t be walking sideways, so your body compensates and goes the other way. You can’t be walking that way sideways, and it compensates back the other way. So now you have these lateral curves, otherwise known as scoliosis."

Toran says such posterior rotation translates into "patellar femoral syndromes and knee pain on that side. The side that rotates anteriorly lifts the ischium and tensions the hamstring, which means a cyclist is going to develop hamstring and calf problems on the side of anterior rotation. Under load of intervals (a training technique involving timed bursts of speed), those minor distortions become magnified over time and over repetitive stress trauma. But this is all predictable from x-rays.

"When I take a set of x-rays, I take them full-spine, where the patient is standing," Toran continued. "Then I’ll have the patient move, turned laterally, and shoot the lumbar pelvic, the thoracic, and then the cervical. When I take these pictures, I can see distortions in the pelvis. You can tell so much, and use it as a predictive indicator for future pathology of vulnerability."

Reinventing the wheel

Rory Cooper, Ph.D., is a professor at the University of Pittsburgh; Cooper won the bronze medal in wheelchair racing at the 1988 Paralympic Games in Seoul, and four gold medals at the 2002 National Veterans Wheelchair Games in Cleveland.

Wheelchair racers average 19 mph in marathons, and achieve speeds of 26 mph on the track and 55 mph downhill in road racing using only hand propulsion. Their most common injuries occur in the shoulder, explained Cooper, who also is chairman of the department of rehabilitation science and technology in the university’s School of Health and Rehabilitative Sciences. Cooper is also director of the Human Engineering Research Laboratories of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System.

|

| Rory Cooper, Ph.D., was a bronze medalist in the 1988 Paralympics. A pioneer in the sport of wheelchair racing, Cooper designed the first racing wheelchair built entirely of non-wheelchair parts. Photo by Warren Parks. Courtesy of Rory Cooper, Ph.D., VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. |

Cooper shares a special research interest in this subject with his associate, Dr. Michael Boninger, associate professor of rehabilitation science and technology, mechanical engineering at the University of Pittsburgh.

The injuries Cooper and Boninger see most are rotator cuff tendinitis, rotator cuff tears, and osteolysis of the distal clavicle.

"You can see it on plain films or MRI. We prefer MRIs for our research, because we’re looking to gain insights into injuries before they happen. By using an MRI, what precursors to injuries do we see? What subtle changes are there, and can we use that information to prevent injuries in the future?" said Boninger, who also is medical director for the Human Engineering Research Laboratories of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and executive director for the Center for Assistive Technology of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System.

"We have been able to find that certain people are developing MRI findings related to how they’re propelling their chairs, and therefore we might be able to give them advice to prevent those findings from becoming something more significant, like a rotator cuff tear," he continued.

In one study, Cooper proved that wheelchair racers had a gross upper-extremity mechanical efficiency of more than 30%, compared with the average for normal activities of 2% to 8%, and that their wrist velocity on impact with the pushrim of a wheelchair was so powerful it could cause enough spike to injure a racer’s shoulder ("Gross mechanical efficiency of trained wheelchair racers," Proceedings of the 1990 International Conference of the IEEE/EMBS, Vol. 12:5, pp. 2311-2312).

If it feels good, why stop?

The experts agree on one trait shared by all high-level athletes, regardless of sport: They will play through pain, often exacerbating injuries into more serious damage.

Ironically, the more money is involved in a sport, the more likely its venues will have medical imaging equipment -- equipment that athletes tend to shun.

The Olympic Polyclinic at the 1996 Atlanta games, for example, was the first Olympics at which MRI and ultrasound were available. The 2000 Polyclinic in Sydney boasted the first CT. Sophisticated medical imaging is now so expedient for athletes, they fear they won’t receive clearance to resume competition.

That’s why Duke’s basketball players are imaged for jumper’s knee with MRI before and after the NCAA season. "With sports that have a lot of jumping and landing, tendons or ligaments can become degenerated over time," Major said. "Several players did indeed have changes that would be diagnostic of jumper’s knee. They don’t complain about the pain; they think they’re supposed to have some, so they’re soaking this or icing that, and that’s ‘expected’ when you’re playing at that level.

"Many have aspirations to play professionally, and if you start complaining that you have pain somewhere, you’re going to get rested and benched. That’s not a good situation when you’re a high-caliber athlete looking for a future beyond college basketball," she said.

As a member of the medical squad for the 1990 Goodwill Games in Seattle, Cooper said that athletes would often let him know that they had no intention of going near the clinic. It was a sentiment that he could understand.

"I’d have to be dead before they pulled me out," Cooper confessed of his medal-winning stint during the 1988 Paralympics "A nasty flu bug went through both the whole Olympic team and the Paralympic team. What choice do you have? You train for years. You get the flu, you just have to work through it and hope the other guys have the flu, too. Olympic athletes don’t get the money until they get the gold medal."

By Sydney SchusterAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

October 8, 2003

Related Reading

MR categorizes acute hamstring injuries for pre-op assessment, September 29, 2003

X-rays and the boys of summer: Imaging goes to bat for baseball injuries, April 15, 2003

Will sports imaging score as a specialty?, February 25, 2002

MRI shoulders burden of skiers' rotator cuff tears, February 23, 2002

Turf Wars in Radiology, Part V: Radiologists, orthopedists put best foot forward, October 1, 2002

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com