Brain MRIs have shown that it's not just concussions that damage the brains of football players but also routine hits over the course of a season, according to a study published online August 7 in Science Advances.

The idea that it's the "big hits" that have the most negative effect is a misperception, noted contributing author Brad Mahon of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh and the University of Rochester in New York.

"Public perception is that the big hits are the only ones that matter. It's what people talk about and what we often see being replayed on TV," Mahon said in a statement released by Carnegie Mellon. "The big hits are definitely bad, but with the focus on the big hits, the public is missing what's likely causing the long-term damage in players' brains. It's not just the concussions. It's everyday hits, too."

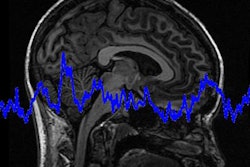

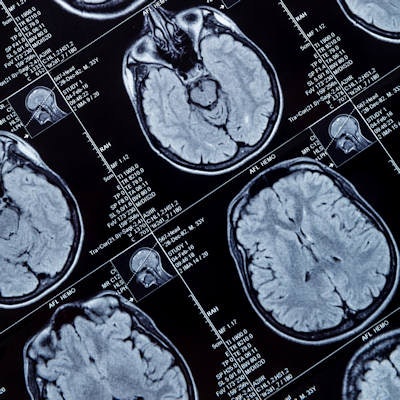

The midbrain is part of a larger rigid structure that includes the brain stem and the thalamus, wrote the team led by Adnan Hirad, PhD, of the University of Rochester. Its relative rigidity causes it to absorb forces differently than surrounding softer tissues, making it susceptible to head hit forces.

"We hypothesized and found that the midbrain is a key structure that can serve as an index of injury in both clinically defined concussions and repetitive head hits," Hirad said in the statement. "What we cataloged in our study are things that can't be observed simply by looking at or behaviorally testing a player, on or off the field. These are 'clinically silent' brain injuries."

The study included 38 University of Rochester football players who had accelerometers in their helmets that measured linear and rotational force for every practice and game. The accelerometers tracked all contact that produced forces of 10 gs or greater. (Astronauts experience 3 gs during liftoff; race car drivers experience 6 gs, and car crashes can produce forces of more than 100 gs, the group noted.) Each player underwent a brain MRI scan two weeks before and one week after the football season.

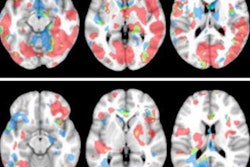

Of the 38 players, only two had concussions during the study timeframe. But a comparison of the post- and preseason MRIs in all the players showed that more than two-thirds had a decrease in the structural integrity of their brain, manifest in reduced white-matter integrity in the midbrain, according to Hirad and colleagues. The amount of white-matter damage correlated to the number of hits to the head players sustained, and the study found that players experienced almost 20,000 hits across all practices and games; of these, the median force was 25 gs.

The findings suggest that return-to-play decisions must be re-evaluated, Hirad concluded.

"Right now, those decisions are made based on whether or not a player is exhibiting symptoms of a concussion like dizziness or loss of consciousness," he said. "Even without a concussion, the hits players are taking in practice and games appear to cause brain damage over time."