MRI reveals that the effect of obesity on brain health may depend not only on how much fat is in the body but also on the areas of the body where the fat is stored, according to a study published January 27 in Radiology.

A team led by Miao Yu, MD, of the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University in China reported that body fat distribution patterns identified on MRI and analyzed via latent profile analysis (LPA) showed that pancreatic-predominant and "skinny-fat" types of fat deposits were linked to adverse neurologic outcomes.

"Our work leveraged MRI's ability to quantify fat in various body compartments, especially internal organs, to create a classification system that’s data-driven instead of subjective," co-author Kai Liu, MD, PhD, said in an RSNA statement. "The data-driven classification unexpectedly discovered two previously undefined fat distribution types that deserve greater attention."

Previous studies have linked obesity to brain/cognitive health, finding that people with higher ratios of visceral fat are at particular risk of adverse brain health outcomes. But there hasn't been much research investigating "specific risks associated with specific fat distribution patterns," Liu said. The team explained that "pancreatic predominant" fat shows a "markedly high concentration of fat in the pancreas compared with other areas of the body," while a "skinny-fat" type has a high fat burden even though it doesn't conform to typical patterns of high obesity.

Yu and colleagues investigated whether fat distribution patterns had different neurologic effects through a study that included data from 25,997 participants in the UK Biobank (including health records and MRI scans of the brain, heart, and abdomen). They classified patients' fat distribution using LPA based on eight body mass index (BMI)-adjusted MRI-derived fat quantification metrics and tracked differences in brain volume, white-matter properties, cognition, and risk of neurologic disorders (comparing these to a benchmark "lean" profile).

The team reported six LPA-identified profiles of body fat distribution, with four of these being "high-adiposity" patterns. Particularly, profile 1 (pancreatic-predominant) and profile 3 (skinny-fat pattern) showed high-adiposity burden:

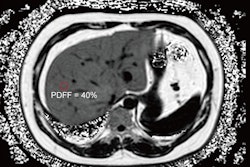

- Pancreatic-predominant profile (profile 1) showed elevated proton density fat fraction (mean BMI-adjusted z score, 2.38 for male participants and 3.01 for female participants; p < 0.001).

- The skinny-fat profile (profile 3) had the highest adiposity burden in most deposit areas despite moderate BMI (six of eight deposit areas for male participants and five of eight deposit areas for female participants; p < 0.001).

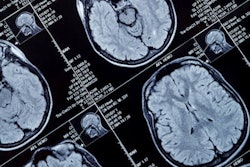

When the team compared these profiles to the benchmark lean profile, it discovered that they were associated with "extensive gray-matter atrophy, elevated white-matter hyperintensity load, accelerated brain aging (p < 0.001 for all), cognitive decline, and increased risk of neurologic disease.

Individuals in the pancreatic-predominant profile didn't have pronounced liver fat compared with those with other profiles, Liu said, noting that "high pancreatic fat accompanied by relatively low liver fat emerges as a distinct, clinically overlooked phenotype."

"In our daily radiology practice, we often diagnose 'fatty liver,'" he said. "But from the perspectives of brain structure, cognitive impairment and neurological disease risk, increased pancreatic fat should be recognized as a potentially higher-risk imaging phenotype than fatty liver."

Group comparisons reveal differences across the six profiles in (A) brain white matter properties, (B) subcortical volume, and (C) cortical volume. (A) Five types of white matter fibers in the brain are shown (top). Sex-specific analysis shows differences among the six profiles in neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) measurements of intracellular volume fraction (ICVF), isotropic or free water volume fraction (ISOVF), and orientation dispersion index (OD), presented separately for male participants (bottom left) and female participants (bottom right). (Fig 3 continues below.)

Group comparisons reveal differences across the six profiles in (A) brain white matter properties, (B) subcortical volume, and (C) cortical volume. (A) Five types of white matter fibers in the brain are shown (top). Sex-specific analysis shows differences among the six profiles in neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) measurements of intracellular volume fraction (ICVF), isotropic or free water volume fraction (ISOVF), and orientation dispersion index (OD), presented separately for male participants (bottom left) and female participants (bottom right). (Fig 3 continues below.)

(B) Seven subcortical areas are shown (top). Sex-specific analysis shows overall interprofile differences in subcortical volume among the six fat distribution profiles (middle) and comparisons of two high-risk profiles (pancreatic predominant and skinny fat) against the benchmark profile (lean) (bottom). (C) Sex-specific analysis shows overall interprofile differences in cortical volume among the six fat distribution profiles (top) and comparisons of two high-risk profiles (pancreatic predominant and skinny fat) against the benchmark profile (lean) (bottom). For the diagrams showing the differences among the six profiles, the color scale indicates the F value. For the diagrams showing the mean difference between high-risk profiles and the benchmark profile, the color scale indicates the regional volume in the high-risk profile compared with the benchmark profile.Images and captions courtesy of Radiology.

(B) Seven subcortical areas are shown (top). Sex-specific analysis shows overall interprofile differences in subcortical volume among the six fat distribution profiles (middle) and comparisons of two high-risk profiles (pancreatic predominant and skinny fat) against the benchmark profile (lean) (bottom). (C) Sex-specific analysis shows overall interprofile differences in cortical volume among the six fat distribution profiles (top) and comparisons of two high-risk profiles (pancreatic predominant and skinny fat) against the benchmark profile (lean) (bottom). For the diagrams showing the differences among the six profiles, the color scale indicates the F value. For the diagrams showing the mean difference between high-risk profiles and the benchmark profile, the color scale indicates the regional volume in the high-risk profile compared with the benchmark profile.Images and captions courtesy of Radiology.

Liu also underscored that people with "skinny-fat" profiles show the "highest fat burden in nearly all areas except the liver and pancreas" -- even though this type "does not fit the traditional image of a very obese person, as its actual average BMI ranks only fourth among all categories."

The study highlights the need for healthcare providers to "understand the risks associated with specific fat distribution patterns," which can guide more personalized treatment and help patients keep their brains healthier, according to Liu.

"Brain health is not just a matter of how much fat you have but also where it goes," he said.

Access the full study here.